The Current Situation

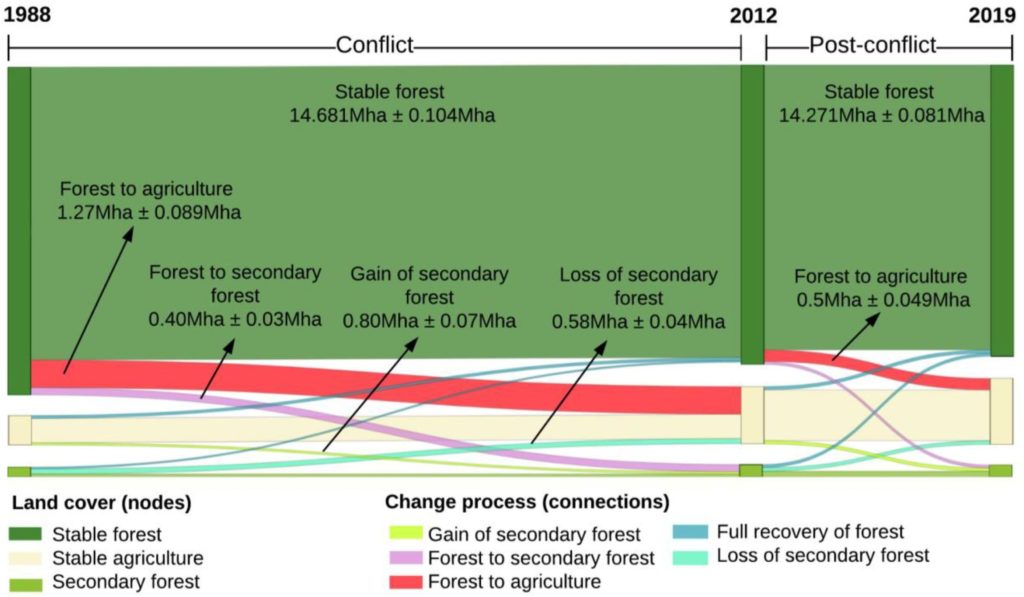

Colombia, the second most biodiverse country in the world, has recently emerged from five decades (1964 – 2016) of internal conflict, after signing a peace agreement with the FARC rebels (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia) in 2016 (Murillo-Sandoval et al., 2020). The cessation and peace accord “End of Conflict and the Construction of Long-Term Peace”, signed in Cartagena was crucial for peace in Colombia (Krause, 2019). The agreement made radical changes to the political and social institutions in forested regions, which consequently has led to widespread deforestation recorded across the country. In the post-conflict period, FARC demobilisation, land grabbing, road construction and illicit activities, fuelled by a governance vacuum has accelerated deforestation in Colombia (Clerici et al., 2020; Negret et al., 2019). These mechanisms have profound and severe impacts for biodiversity and ecosystem services, especially within Colombia’s protected areas (PAs).

In Colombia, 14 % of continental land is categorised is a protected area, which are managed geographical spaces of high biodiversity, conservational and indigenous importance (Bonilla-Mejia & Higuera-Mendieta, 2019). Accelerated deforestation in the post-conflict period has been recorded using satellite data by Clerici et al., (2020), Murillo-Sandoval et al., (2020) and Murillo-Sandoval et al., (2021) within and surrounding Colombia’s PAs (Figure 1). However, the impacts of post-conflict development and the effectiveness of PAs to halt forest loss during the peace and development process are relatively understudied. Therefore, this report aims to contribute towards filling this knowledge gap. This research examines deforestation in post-conflict Colombia (2016-2019) within PAs and surrounding 10 km buffer zones, by comparing to levels of forest loss found during the conflict period (2012-2015).

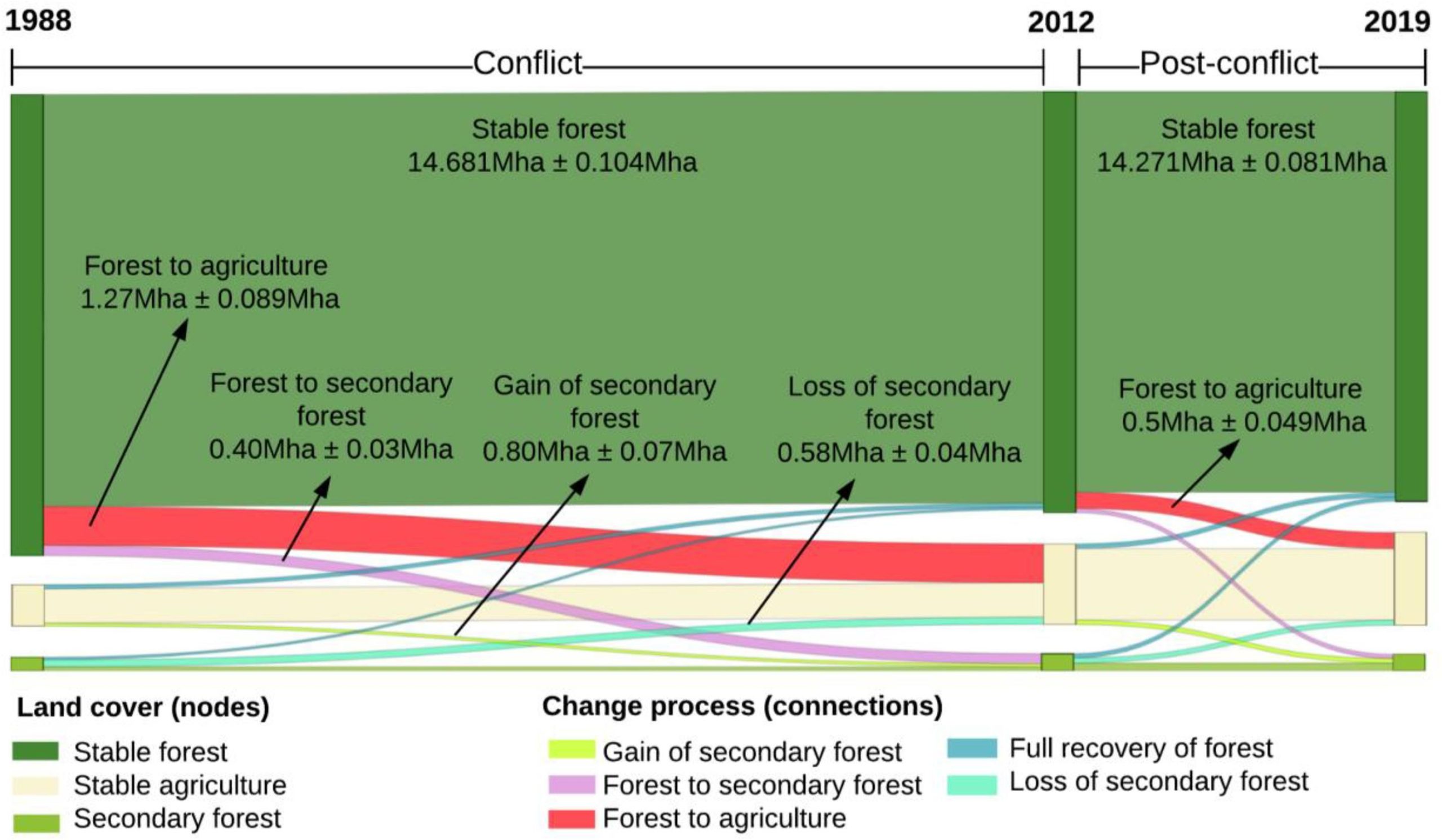

Figure 1 Sankey diagram showing transitions between three main land cover classes (Stable forest, stable agriculture and secondary forest) during and between conflict and post-conflict period for the Andean Amazon Transition Belt (Source: Murillo-Sandoval et al., 2021).

Methods

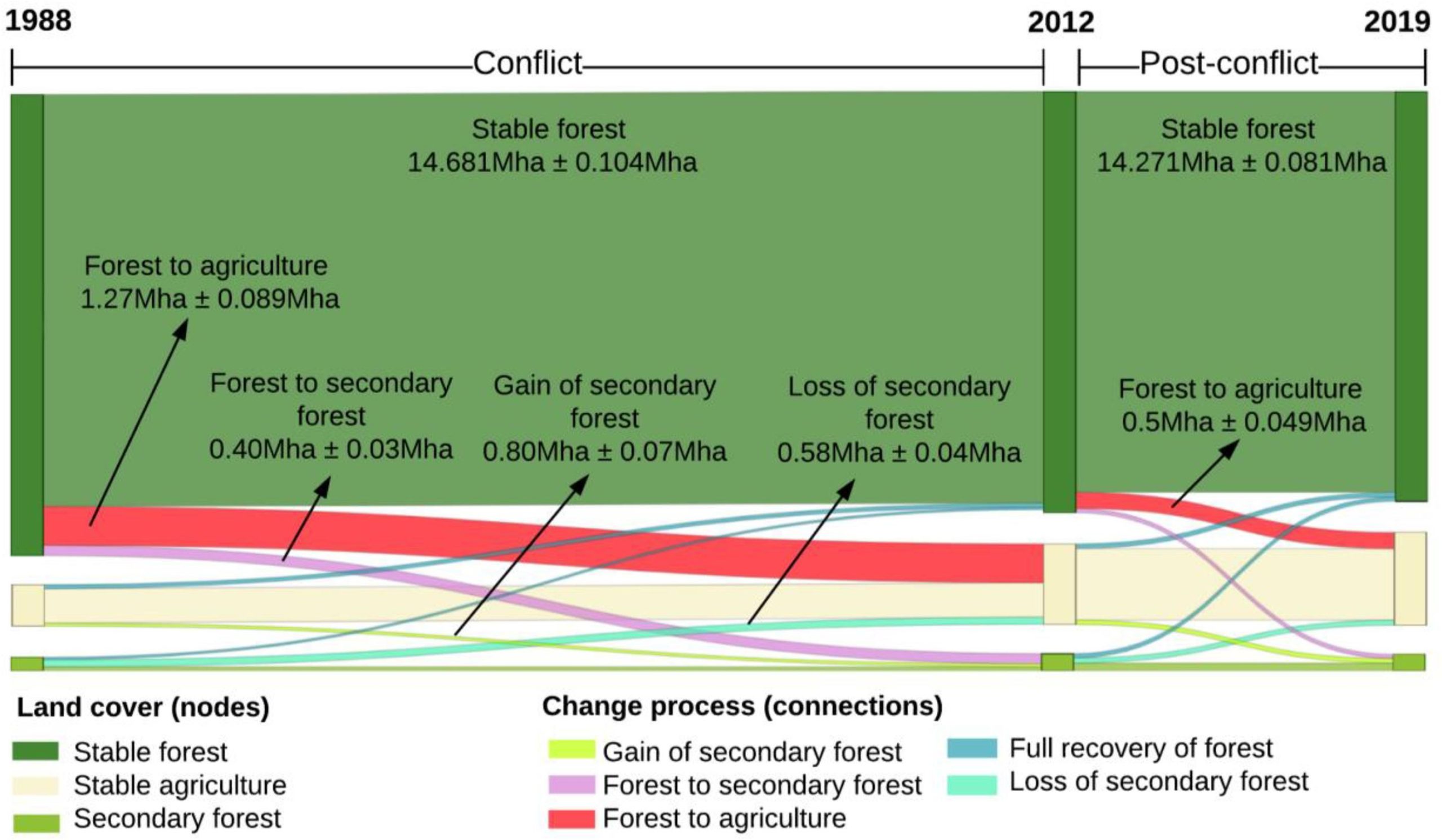

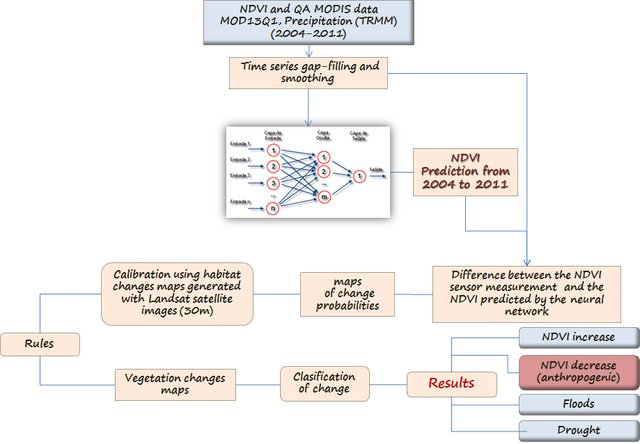

39 out of 59 nationally PAs (n= 59) were selected using Python from the World Database on Protected Areas, as they are continental forest national parks and should be enforced by the government. The global monitoring of forests has accelerated in the last decade as satellite imagery has become the most accurate method to assess forest clearance across the world. It is the main tool that allows forests to be monitored consistently at a global scale (Hansen et al., 2013). Terra-I is a near-real-time forest loss monitoring system for Latin America (Reymondin et al, 2019). Terra-I uses satellite data and computational neural networks to detect anthropogenic changes in vegetation every 16 days, with data available since 2004, (Figure 2) (Reymondin et al., 2019).

Six image tiles for each year of the time series (2012-2019) with a spatial resolution of 250m, were mosaiced to cover a shapefile of Colombia. In ArcGIS Pro, the mosaics were converted to a raster format and clipped to the Colombia shapefile. All datafiles were projected to MAGNA-SIRGAS/Colombia Bogotá zone: EPSG 3116, most suitable for large scale spatial analysis across the country (Clerici et al., 2020). Terra-I data has a high temporal resolution and shows the cumulative 16-day detection of forest loss. To obtain the desired annual change, the pixels in the mosaiced raster were reclassified to represent those that remained unchanged for the year (0) and those that were detected as forest loss (1, includes >1).

ArcGIS Pro was used to construct 10 km buffers around PAs, to analyse deforestation within PAs and surrounding 10 km buffers from 2012 to 2019 (Clerici et al., 2020). R Studio was used to calculate the difference in deforestation within each PAs before (2012-2015) and after (2016-2019) the peace agreement. This was repeated for each of the 10km buffers. This method was adapted from Clerici et al., (2020).

Figure 2 Satellite imagery and computational networks used to detect anomalies in the NDVI product time series of the Terra-I system (Source: Reymondin et al., 2012)

Deforestation within Protected Areas

The results showed that 14 out of 39 PAs (36 %) experienced increased forest loss and 17 PAs (44 %) experienced reduced forest loss in the post-agreement period (2016-2019), compared to during conflict period (2012-2015). Reduced forest loss within PAs was mostly negligible, except for Picachos which experienced 25 km2 less of forest loss in the post-conflict period. However, 8 PAs experienced no change or forest loss for the time series. Overall, this resulted in a 91 % change in forest loss between the two time periods, an equivalent of 152 km2 of additional loss of protected forest.

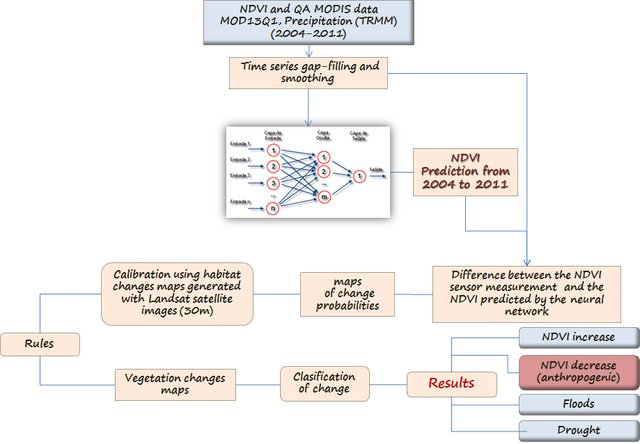

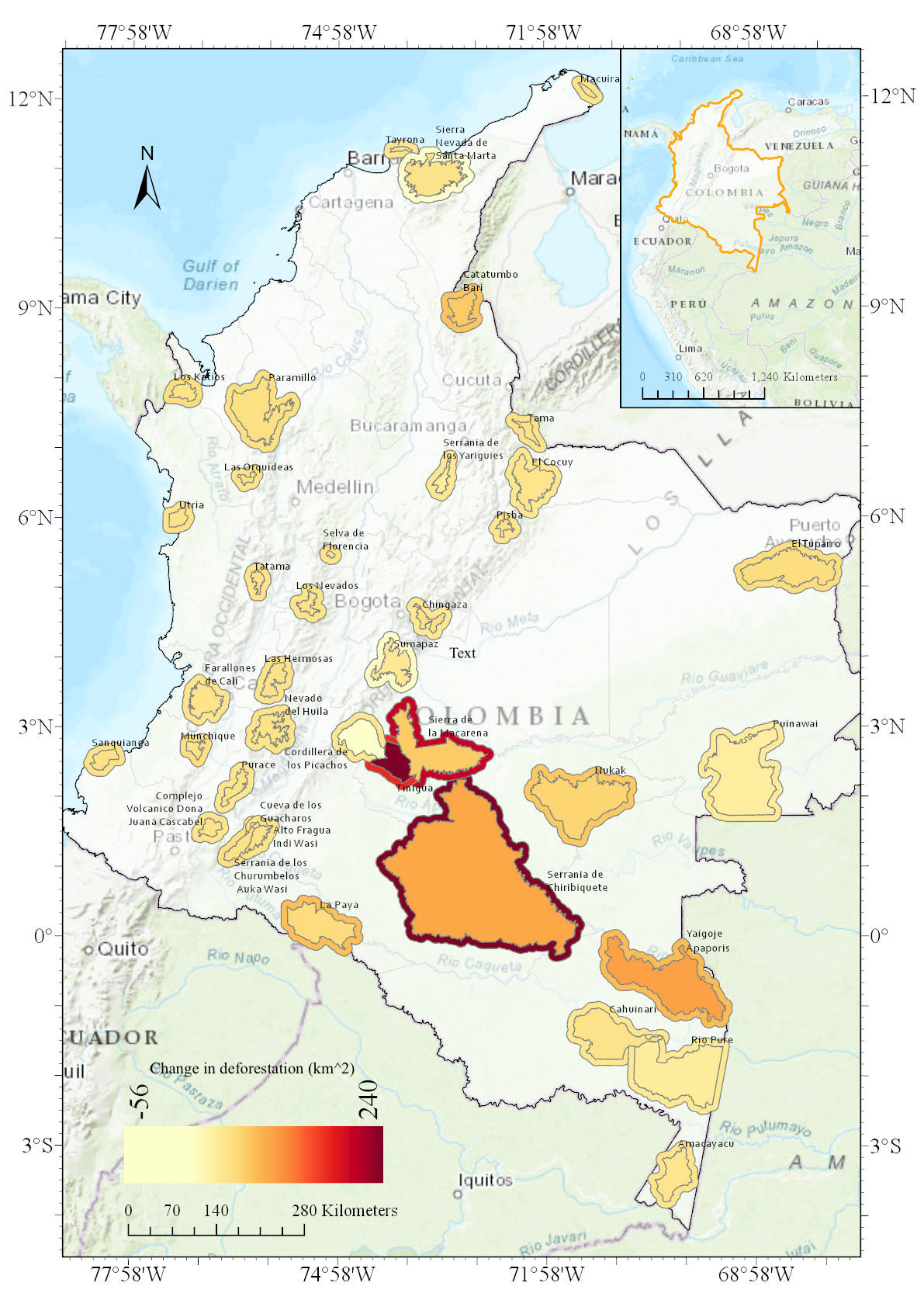

Greatest upswings were found within PAs located in the Colombian Amazon region such as Tinigua, Yaigojie Apaporis and Chiribiquete as well as in the Northern Andean region within Catatumbo Bari (Figure 3). High deforestation found within specific PAs in the Amazon is alarming such as Chirbiquete, the largest national rainforest PA in the world (Bonilla-Mejia & Higuera-Mendieta, 2019). Deforestation within these PAs is striking as their International Union for Conservation of Nature status (IUCN) should prohibit forest clearing activities occurring within them (Clerici et al., 2020).

Weak land governance, ineffective physical and legal presence across the country coupled with FARC withdrawal, has led to the acceleration of spontaneous and unplanned land occupation by non-state actors (Negret et al., 2019). Unregulated land seizures displace local communities in order to clear forests for a variety of economic activities such as cattle ranching, illicit crops and mining which consequently drives habitat fragmentation and destruction in the post-conflict period (Clerici et al., 2020).

On the other hand, reduced deforested recorded within some PAs in the post-conflict period could be attributed the recent countrywide military operations established to tackle deforestation and illegal mining, especially within Colombia’s PAs. The operations began in 2019, called ‘Operation Artemis’, deployed by Colombia’s president Iván Duque (Furumo & Lambin, 2020). However, the operations that have recovered forests, have emptied them of its people by military force known as the ‘militarisation of environmental conservation’. This has been the case in Nunkak protected area in the Amazon, which is home to one of the world’s last remaining nomadic tribes (Podur, 2021).

Indigenous people are considered the best guardians of the forest; deforestation rates are up to 50% lower in indigenous reserves than elsewhere. Therefore, instead of removing indigenous people from the forests, communities should be given security and land tenure to protect them, a concept called ‘Parque con Campesinos’. Land reform, sustainable initiatives, stronger governance, and forest monitoring are the necessary steps to protect forests, associated ecosystem services and biodiversity in post-conflict Colombia.

Figure 3 Change in deforestation within each PA and surrounding 10 km buffer before (2012-2015) and after (2016-2019) the peace agreement.

Deforestation within 10km buffers

The results showed that 19 out of 39 buffers (48 %) surrounding PAs experienced increased forest loss and 18 buffers (46 %) experienced decreased forest loss in the post-agreement years, compared to during the conflict. Only 2 buffers experienced no change or forest loss for the time series. This resulted in 149 % change in forest loss between the two time periods, an equivalent of 612 km2 of additional forest loss within a 10 km radius of PAs.

Greatest upswings of forest loss were found within buffers surrounding PAs in the Colombian Amazon such as Chiribiquete, Macarena and Nunkak, as well as in the Northern Andean region such as Las Hermosas (Figure 3). High forest loss within buffer regions could be attributed to a variety of forest clearing activities such as mining and cattle ranching which are not prohibited from occurring within close proximity to the PAs.

There seems to be a linkage between high forest loss occurring within PAs and associated buffer zones such as Chiribiquete, Macarena and Nunkak. Forest loss within the buffers is a conservation concern, as in the post conflict period forest loss contributed to 20% of the overall forest loss occurring within Colombia. Without further protection forest clearing activities in buffers could leak into the protected areas they surround. Managing these buffers under Sistema Nacional de Áreas Protegidas (SINAP) could reduce the country’s overall forest loss and provide a stronger protective barrier around PAs and consequently, reduce forest loss within them.

Conclusions

The research demonstrates that forest loss increased within PAs and buffers following the peace-agreement in 2016, in post-conflict Colombia. The Colombian government must now provide the momentum for sustainable economic development that involves a suite of conflict sensitive strategies for the protection of forests and livelihoods. Strengthening governance, land reform, forest monitoring and sustainable initiatives are the necessary steps to protect forests and biodiversity in post-conflict Colombia and PAs. Globally, forest conservation and the protection of natural resources must be at the focus of peace accords.

References

Bonilla-Mejía, L. and Higuera-Mendieta, I., 2019. Protected areas under weak institutions: Evidence from Colombia. World Development, 122, pp.585-596.

Clerici, N., Armenteras, D., Kareiva, P., Botero, R., Ramírez-Delgado, J.P., Forero-Medina, G., Ochoa, J., Pedraza, C., Schneider, L., Lora, C. and Gómez., C., 2020. Deforestation in Colombian protected areas increased during post-conflict periods. Scientific reports, 10(1), pp.1-10.

Hansen, M.C., Potapov, P.V., Moore, R., Hancher, M., Turubanova, S.A., Tyukavina, A., Thau, D., Stehman, S.V., Goetz, S.J., Loveland, T.R. and Kommareddy, A., 2013. High-resolution global maps of 21st-century forest cover change. science, 342(6160), pp.850-853.

Krause, T., 2020. Reducing deforestation in Colombia while building peace and pursuing business as usual extractivism?. Journal of Political Ecology, 27(1), pp.401-418.

Murillo-Sandoval, P.J., Gjerdseth, E., Correa-Ayram, C., Wrathall, D., Van Den Hoek, J., Dávalos, L.M. and Kennedy, R., 2021. No peace for the forest: Rapid, widespread land changes in the Andes-Amazon region following the Colombian civil war. Global Environmental Change, 69, p.102283.

Murillo-Sandoval, P.J., Van Dexter, K., Van Den Hoek, J., Wrathall, D. and Kennedy, R., 2020. The end of gunpoint conservation: Forest disturbance after the Colombian peace agreement. Environmental Research Letters, 15(3), p.034033.

Negret, P.J., Sonter, L., Watson, J.E., Possingham, H.P., Jones, K.R., Suarez, C., Ochoa-Quintero, J.M. and Maron, M., 2019. Emerging evidence that armed conflict and coca cultivation influence deforestation patterns. Biological Conservation, 239, p.108176.

Podur, J., 2021. Is Colombia’s Military Displacing Peasants to Protect the Environment or Sell Off Natural Resources?. [online] Pressenza. Available at: <https://www.pressenza.com/2021/05/is-colombias-military-displacing-peasants-to-protect-the-environment-or-sell-off-natural-resources/> [Accessed 5 September 2021].

Reymondin, L., Paz-García, P., Tello, J.J., Coca-Castro, A., Bautista, O. and Menzinger, B., 2019. User Manual. Training Manual Terra-i. Version 2. CIAT Publication No. 477. International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT), Cali, Colombia. 114 p.

WDPA., 2020. Protected Planet: The World Database on Protected Areas (WDPA) and World Database on Other Effective Area-based Conservation Measures (WD-OECM) [Online], December 2020, Cambridge, UK: UNEP-WCMC and IUCN. Available at: www.protectedplanet.net. Accessed 30 December 2020.