Every map tells a story, but only if it knows where it is. Coordinate systems are the framework that makes spatial data meaningful. They allow satellites to position a ship in the middle of the Pacific, help surveyors align construction plans, and enable global companies to run location-based services at a planetary scale. Without them, spatial data is just a scattered set of numbers.

This article explores the foundations of coordinate reference systems (CRSs), the technologies that support them, and the growing ecosystem of organizations, tools, and portals that keep the world aligned.

What Is a Coordinate Reference System?

A coordinate reference system defines how locations on Earth are measured, represented, and stored. It encodes mathematical rules so that latitude/longitude values correspond to real-world points, or planar grid coordinates reliably map to the same ground location every time.

The global registry of such definitions is maintained via the EPSG Geodetic Parameter Dataset, widely used in GIS software as the source of canonical CRS definitions including datums, ellipsoids, and transformation parameters.

The Globe vs. the Map Sheet

A helpful analogy is the difference between a globe and a paper map. The globe represents Earth’s true shape. A map sheet is a flattened version created for convenience. Both describe the same world, but they follow different mathematical rules.

A coordinate reference system ties those two representations together so that data captured on a curved planet can be used on flat screens, printed plans, navigation devices, and analysis tools.

GCS vs. PCS: Why Both Exist

CRSs generally fall into two categories: Geographic Coordinate Systems (GCSs) and Projected Coordinate Systems (PCSs). Understanding why both exist helps explain many of the everyday challenges geospatial professionals face.

Geographic Coordinate Systems

These use angular measurements (latitude and longitude) to describe positions on the Earth’s surface. When navigation apps or global datasets reference “WGS84,” they mean a geographic system based on a mathematical ellipsoid that approximates Earth’s shape.

A GCS is ideal for global datasets, satellite imagery, and any workflow where distortions must be minimal over long distances.

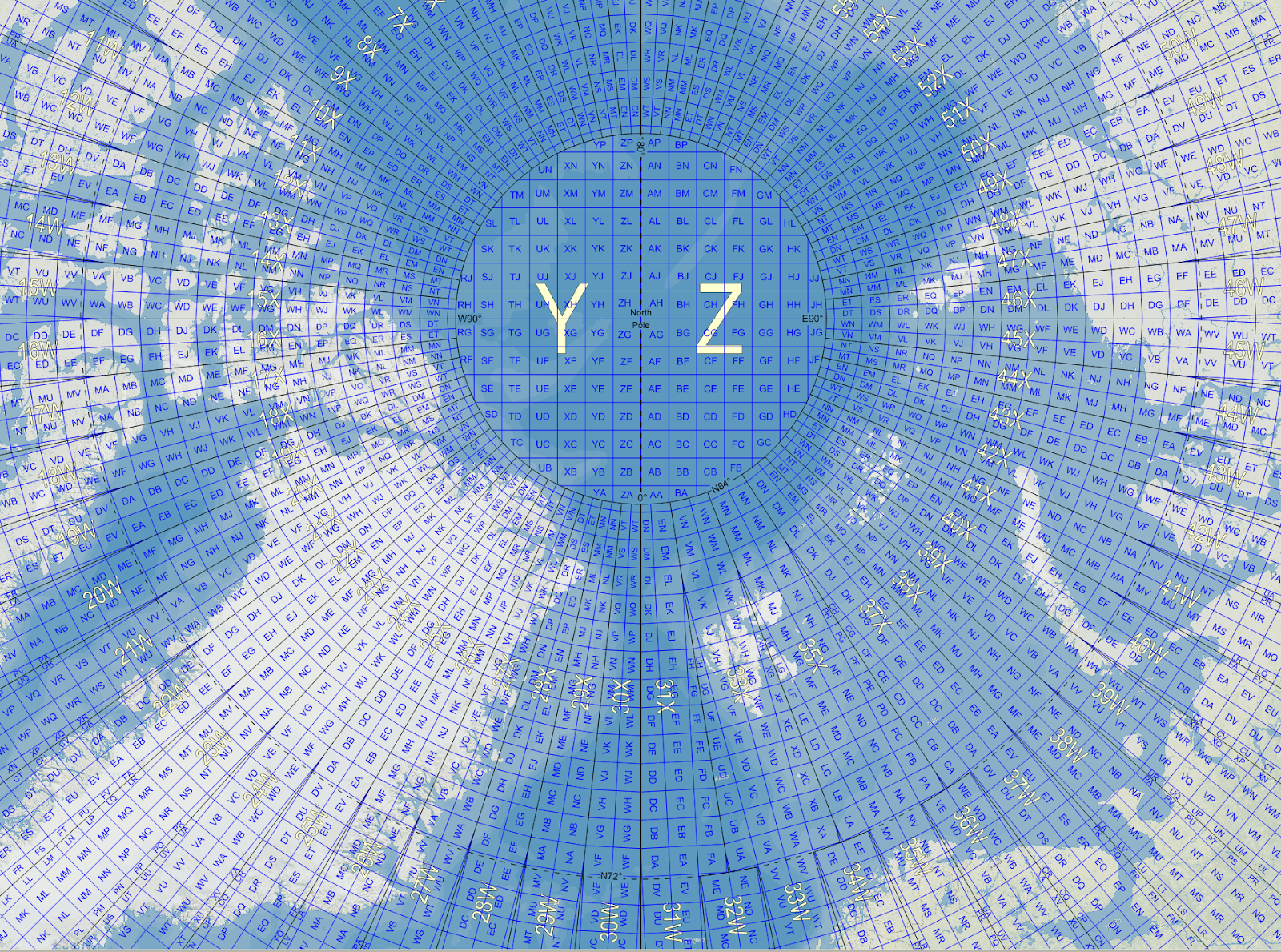

Projected Coordinate Systems

A PCS translates the Earth’s curved surface into planar coordinates, usually in meters. This makes it easier to measure distances, calculate areas, and work with engineering or planning applications that demand precision in the local context.

Examples include UTM zones, British National Grid, State Plane systems in the United States, and national grids used by many surveying agencies.

Why We Need Both

Sometimes you need the “big picture,” such as tracking flights or modeling climate patterns. Other times, you need precise, flat measurements for infrastructure, construction, or utilities. CRSs bridge these two modes of mapping, allowing datasets to move between global and local needs without losing meaning.

Datums and Ellipsoids: WGS84, NAD83, and Friends

A datum defines the origin and orientation of a coordinate system. It answers questions like: Where is Earth’s “zero point”? How is the ellipsoid positioned relative to the planet’s geoid?

Most CRSs rely on a datum paired with an ellipsoid: a smooth mathematical surface that approximates Earth’s slightly flattened shape.

Well-Known Datums

- WGS84 – The global standard used by GPS, satellites, and most international datasets.

- NAD83 – Widely used in North America, especially for engineering, utilities, and surveying.

- ETRS89 – The reference frame for Europe, stable relative to the Eurasian tectonic plate.

- GDA2020 – Australia’s updated datum aligned with modern satellite positioning.

EPSG Codes and Tools

The geospatial community relies on EPSG codes, a standardized catalog of CRSs maintained through a global registry. Codes like EPSG:4326 (WGS84) or EPSG:3857 (Web Mercator) act as shorthand for complex definitions. Modern coordinate systems are supported by an ecosystem of open and commercial tools:

EPSG.io – A search portal for finding CRSs by region, keyword, or code.

PROJ – A widely used open-source library for performing coordinate transformations.

GDAL – A foundational toolset that applies CRS definitions to geospatial datasets.

QGIS, ArcGIS, PostGIS – Platforms that consume and manage CRS definitions for analysis.

Global Companies and Their Role in Keeping Coordinate Systems Modern

A growing number of global companies influence how CRSs evolve and how they are used at scale. These organizations not only consume CRSs; they also help shape best practices, support open standards, and develop new approaches for global-scale spatial alignment.

- Google, Apple, and Microsoft rely on global coordinate standards for routing, geocoding, and 3D mapping.

- Esri and Hexagon integrate CRS tools deep into enterprise GIS systems.

- OpenStreetMap depends on consistent coordinate alignment to crowdsource global mapping.

- Airbus, Maxar/Vantor, Planet, and Satellogic produce massive volumes of Earth observation imagery that rely on accurate CRSs for stitching, calibration, and downstream analytics.

- Mapbox, CARTO, and Safe Software offer location platforms that automatically handle CRS transformations for developers.

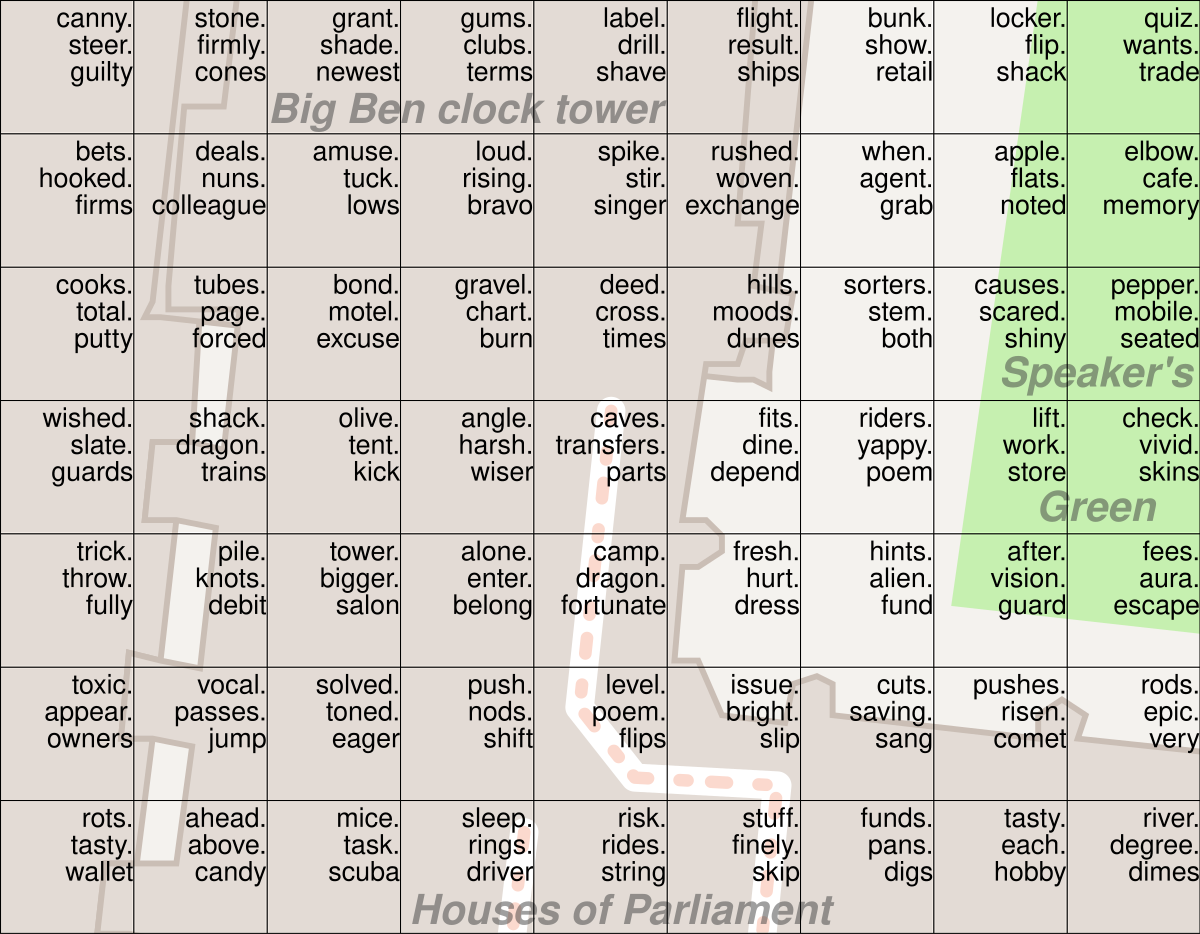

Unique and Unusual Coordinate Systems

Most people know global and national CRSs, but a few unusual or niche systems highlight the diversity of mapping:

Web Mercator (EPSG:3857) – A distorted projection used by almost every web map. It looks familiar but inflates areas near the poles, making Greenland appear larger than Africa.

GCJ-02 and BD-09 (China) – Encrypted coordinate systems required for commercial mapping, introducing offsets from WGS84.

What3Words – Converts the planet into 3-meter squares labeled with unique three-word combinations.

Military Grid Reference System (MGRS) – A global alphanumeric grid used in defense and emergency response.

These systems show how coordinate design reflects political, technical, and cultural choices.

Where the Field Is Heading

Modern coordinate systems are becoming more dynamic, more automated, and better suited to an Earth that is constantly moving.

Two major trends are shaping the future:

- Dynamic datums – Instead of fixed frames, next-generation CRSs can shift over time to reflect tectonic movement. Agencies in Australia, New Zealand, and the U.S. are already preparing for broader adoption.

- Real-time transformations – Cloud mapping platforms increasingly apply CRS transformations automatically, allowing users to work across regions and systems without manual intervention.

In parallel, global companies are standardizing pipelines that integrate satellite data, sensor networks, and AI, creating spatial frameworks that operate at a massive scale.

Interactive Resources:

For readers who want to experiment with map projections, the D3 Geo collection on Observable offers live notebooks that demonstrate everything from Mercator to Orthographic, with sliders for rotation, scale, and translation. These notebooks are fully interactive and allow you to visualize distortions and projection behavior in real time.

Coordinate systems are the invisible architecture of the geospatial world. They ensure datasets align, maps remain consistent, and decisions can be trusted. CRSs play a role in modeling cities, planning infrastructure, analyzing climate trends, and building global mapping platforms. Understanding how they work and selecting the right one for each task is one of the most valuable skills in geospatial practice today.

Related resources:

Geo‑Projections.com – interactive projection reference and demos

Did you like this post? Read more and subscribe to our monthly newsletter!