Public participation is a fundamental element of urban planning. And in practice, perhaps also the most difficult part of the profession. All those working with planning know that meeting residents, advocate groups and other stakeholders can sometimes be a burden.

People are often hard to reach to begin any kind of conversation about development. And when you manage to do so, the only thing they seem to be able to communicate is “NO!”. The proliferation of social media platforms has also taken much of the conversation activity online. Yet many planners find feedback generated through these channels hard to handle and use.

The good news is that there’s hope. Our experiences from Helsinki show that people’s interest in their surroundings hasn’t gone anywhere. Capturing residents’ excitement just needs new methods.

A good idea for planners is to begin exploring the growing selection of user-friendly tools for engagement and data collection. Our solution to reconnecting planners and communities is Maptionnaire.

Maptionnaire is a map-based system for building questionnaires and discussion forums that link citizen feedback to specific locations in communities. It’s a handy tool for transforming discordant citizen insight into easily digestible pieces of information.

Here are a few examples how Maptionnaire has helped shape Helsinki.

Crowdsourcing for Helsinki’s New Masterplan

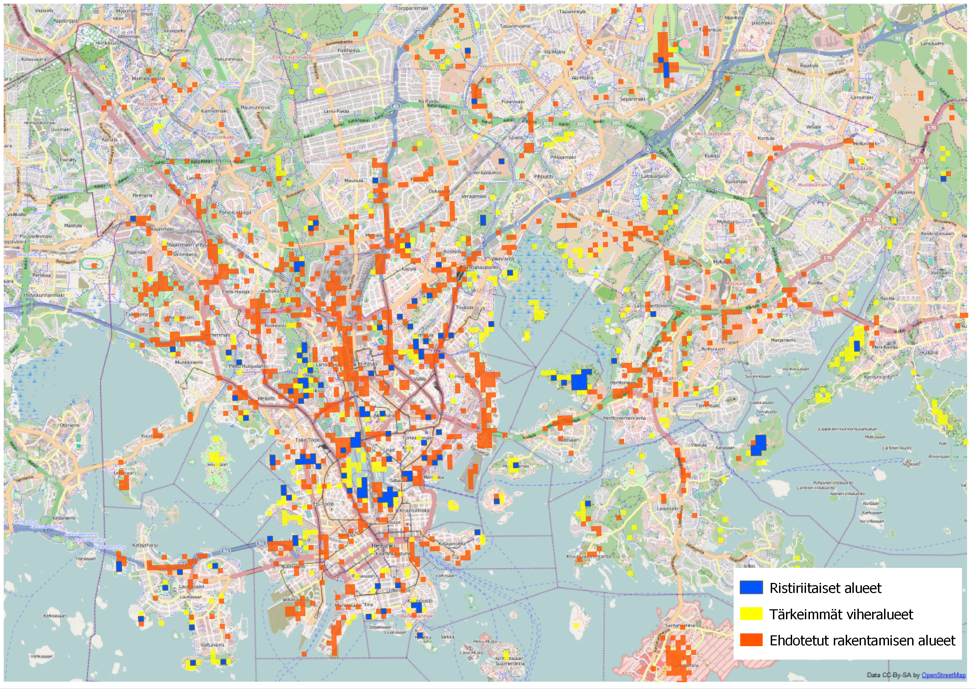

Helsinki is adopting a new general plan that will guide the city’s development for the next decade or so. The City Planning Department kicked the project off with hearing from the public. Using Maptionnaire, they empowered residents to freely map directions where the city should grow. The study attracted 4 700 respondents to mark around 33 000 experience-based ideas on a map of the city.

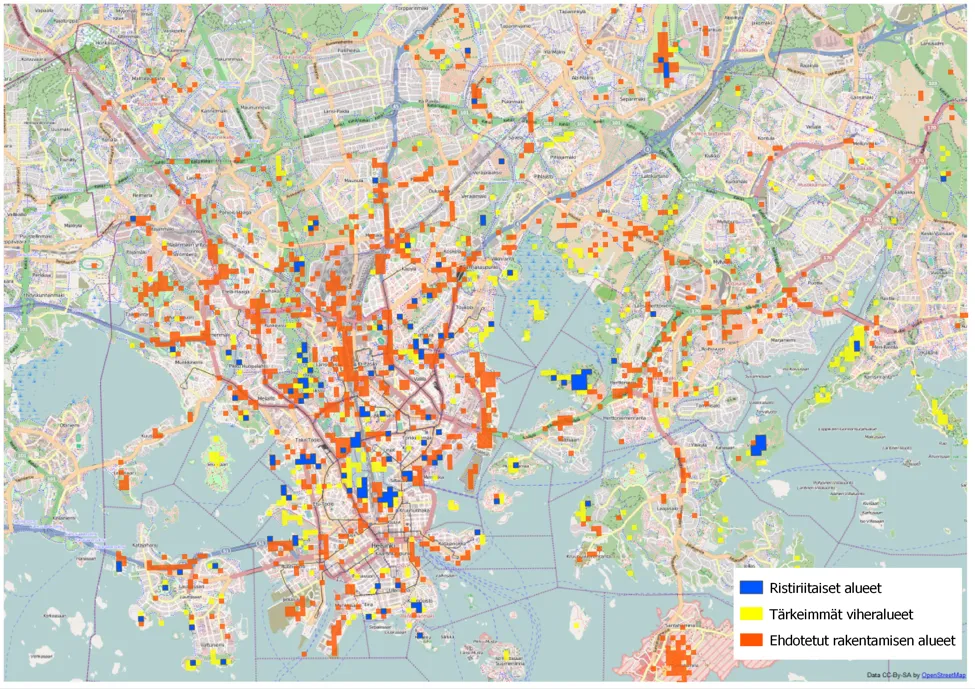

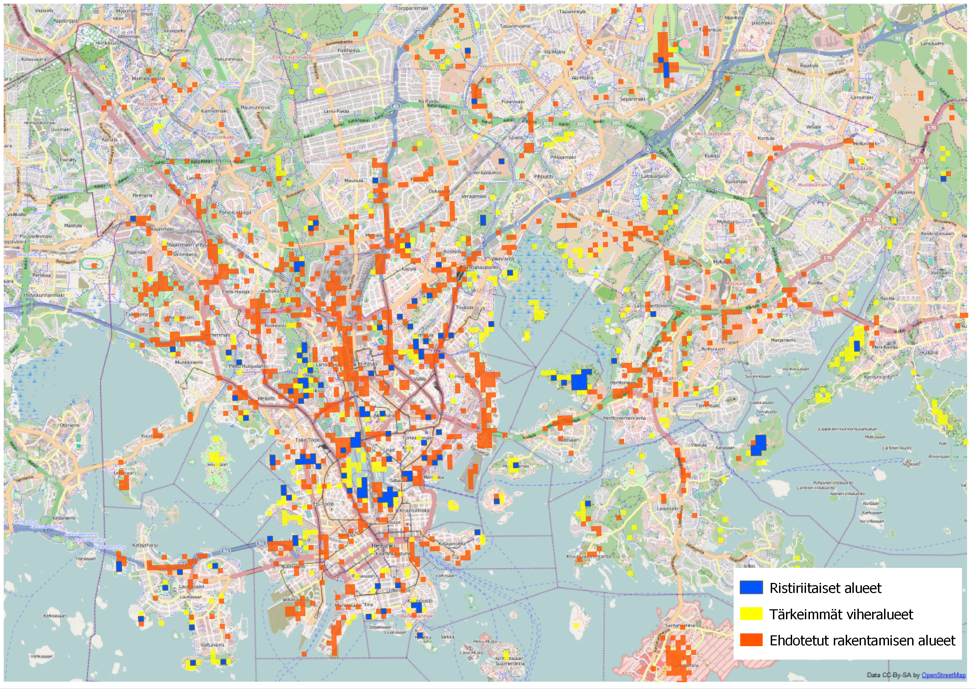

Mapped citizen insight for future Helsinki. Orange for the most desirable development spots, yellow for the most important green areas, and blue for conflicting interests. Image by Mapita.

Mapped citizen insight for future Helsinki. Orange for the most desirable development spots, yellow for the most important green areas, and blue for conflicting interests. Image by Mapita.

The results were astounding. Contrary to popular belief and attitudes often expressed via neighborhood associations, the study showed that Helsinkiers welcome new development along urban highway corridors and other already built-up areas. The consultation also pointed out areas where new construction would generally be unacceptable or controversial, giving planners a sense of no-go zones.

A big discovery was who answered. The city received a lot of input from conventionally hard-to-reach demographic groups like parents and young people.

The project’s results got used as such to steer the plan drafting process as well as inputs for a series of workshops where residents continued planning what their neighborhood could look like in 2050.

Nourishing Bottom-up Urban Planning

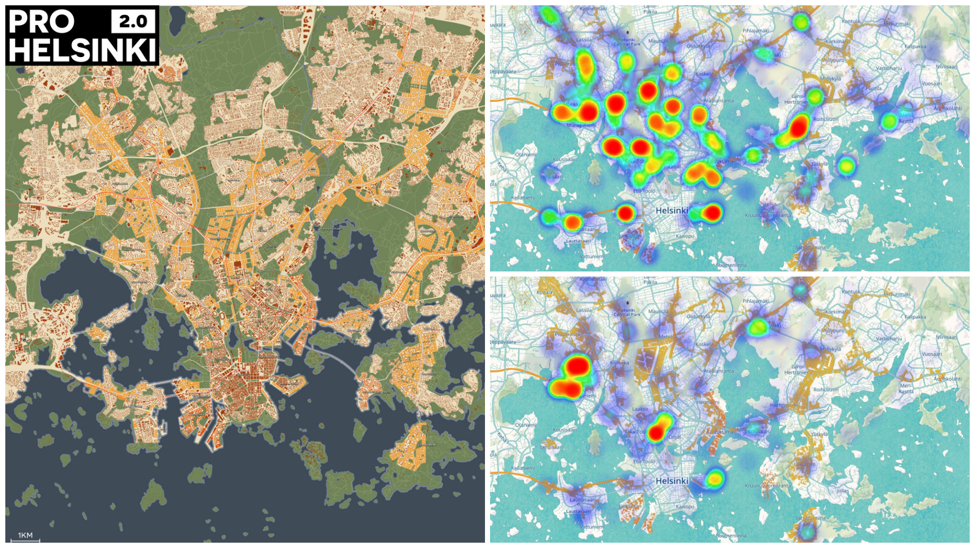

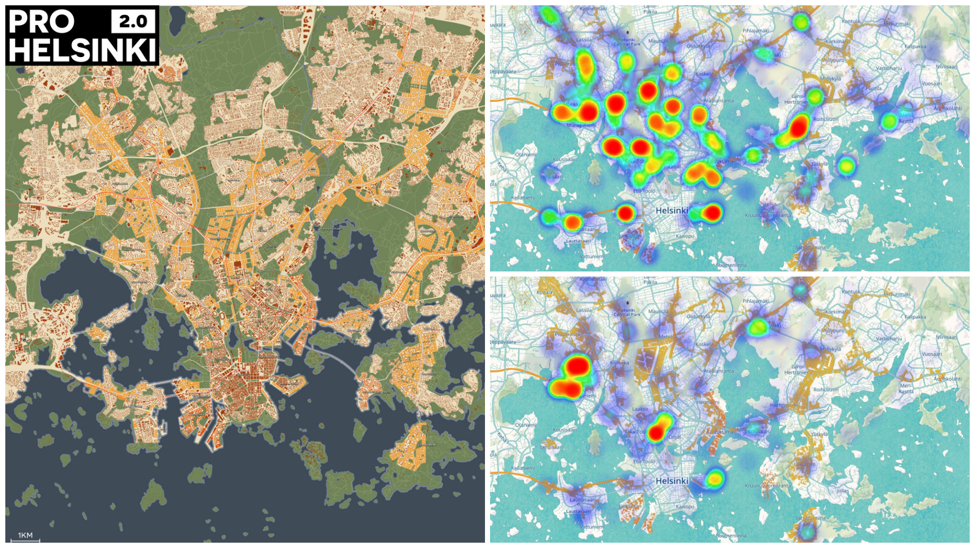

Maptionnaire has also entered the world of urban development “activism”. A voluntary working group called Urban Helsinki felt there was a need to diversify discussions about Helsinki’s new master plan project. They decided to propose something better than the city administration did. The group came up with Pro Helsinki 2.0, an unofficial master plan which illustrates how Helsinki could develop in a more sustainable manner by reviving the urban block.

The starting point for the plan was taken from the City Planning Department’s citizen engagement project and especially its findings about what the younger generation wants future urban development to look like. In their plan drafting process the activists advanced the ideas expressed by residents in the online consultation through workshops, social media interaction, and discussions with planners and other stakeholders.

Left: The alternative master plan. Right: Results from the feedback questionnaire. The proposed development in the plan was imported into Maptionnaire as its own information layer. The top image is for most favorable ideas and the bottom image for top places of improvement. Images by Urban Helsinki.

Left: The alternative master plan. Right: Results from the feedback questionnaire. The proposed development in the plan was imported into Maptionnaire as its own information layer. The top image is for most favorable ideas and the bottom image for top places of improvement. Images by Urban Helsinki.

After publishing their plan, the group used Maptionnaire to release an open map-based survey of their own to receive feedback from Helsinki’s residents on their work. Hundreds of people shared their thoughts.

Following feedback-inspired improvement work, Pro Helsinki 2.0 got fine-tuned to become a powerful tool for forcing planners and politicians to reflect their thinking against the bottom-up plan and exploring the validity of their arguments for what makes a great city.

Uncovering user perceptions

Parallel to day-to-day urban planning, research institutes and special interest groups are constantly using Maptionnaire to collect datasets to stimulate planners to develop more user-friendly urban environments.

The Research Foundation for Studies and Education Otus for example recently conducted a large study to produce knowledge about how students live and would like to live in the Helsinki metropolitan area. The results deliver food for thought in integrating more student-friendliness into urban development and for building places that will make students stick around after graduation.

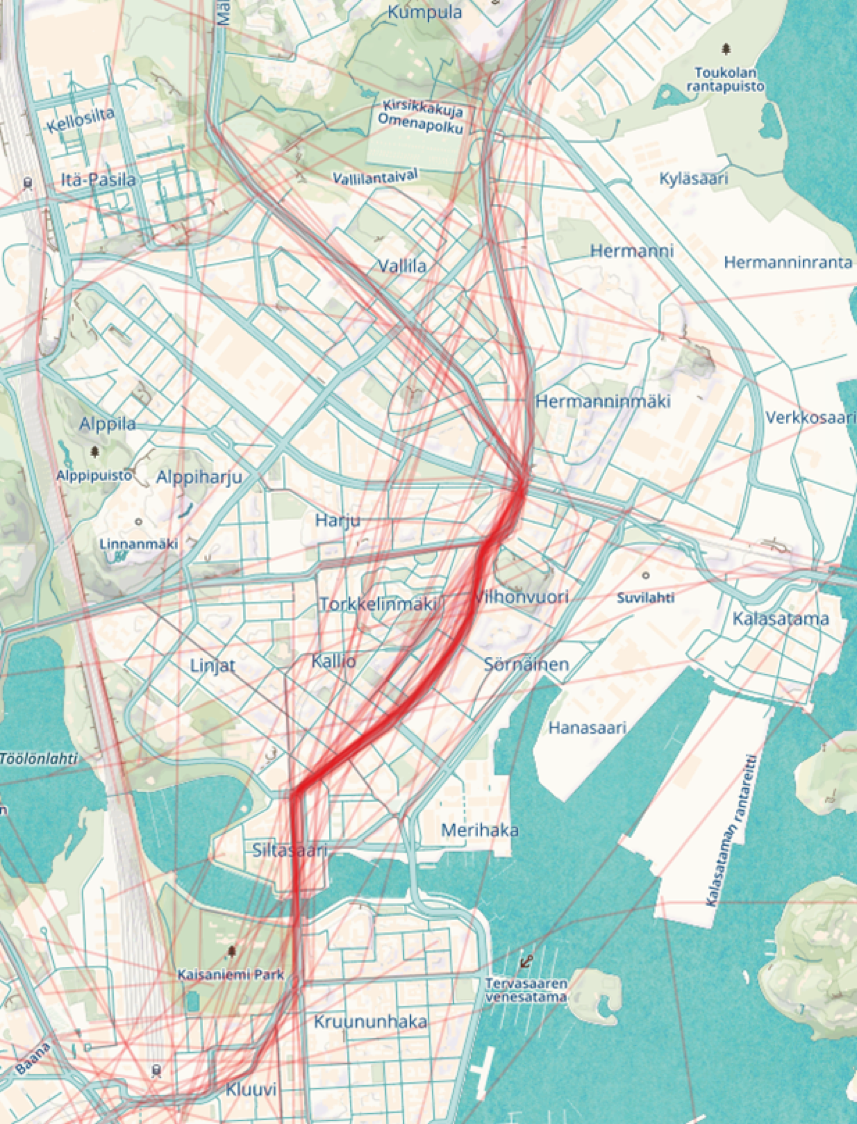

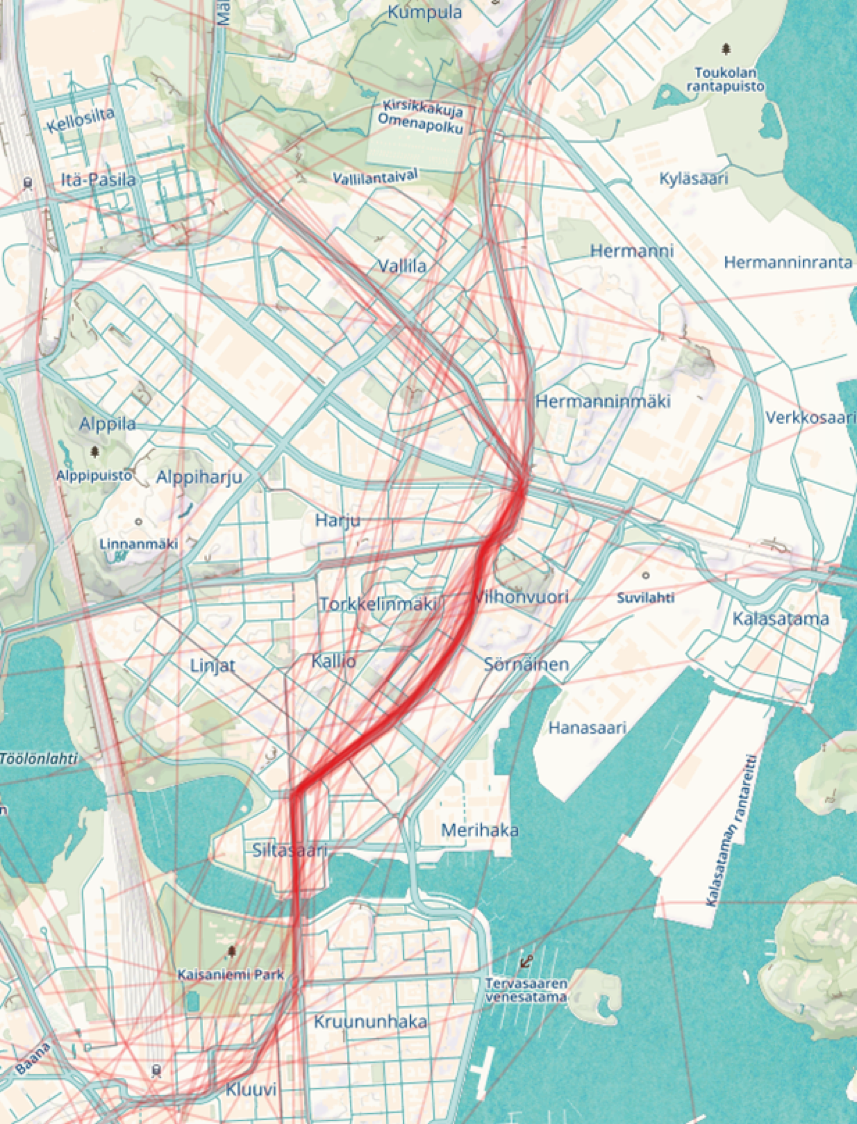

In the Otus project, students clearly indicated that there is a need to better the cycling infrastructure between the University of Helsinki’s two inner city campuses.

In the Otus project, students clearly indicated that there is a need to better the cycling infrastructure between the University of Helsinki’s two inner city campuses.

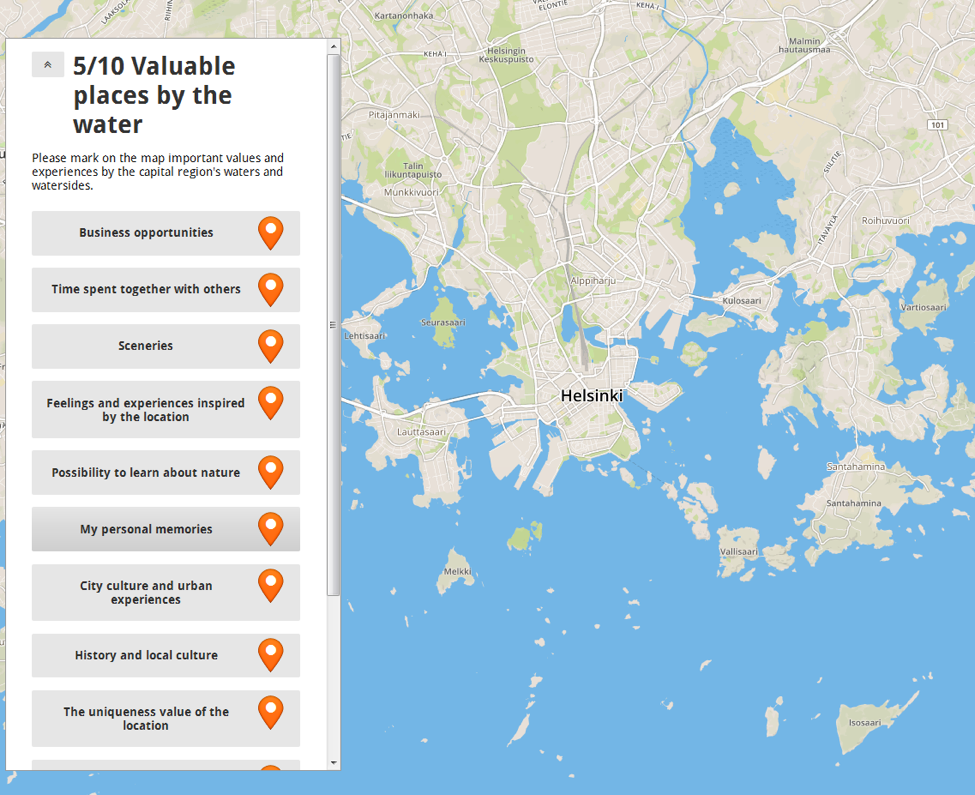

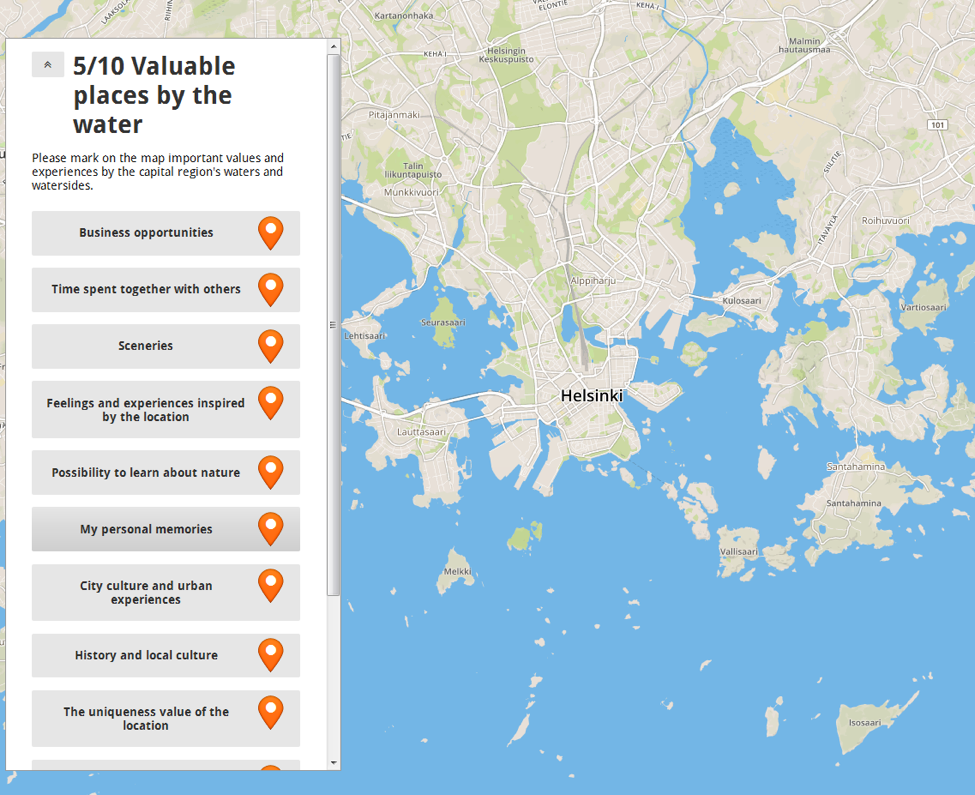

Another interesting example is with the ENJUSTESS research project. An interdisciplinary academic consortium is using Maptionnaire to gather a better understanding of urban water areas in the life of urban dwellers. Water is an important part of urban culture, the scenery and the nature experiences of urban residents. The results of the experience-mapping help to uncover the urban structural and design characteristics of great waterfront areas, which, eventually, allow making sure that people are able to enjoy the city’s shoreline just in the way they would like to.

The ENJUSTESS research focuses on mapping experiences by the water.

The common factor defining these examples from Helsinki is that they have high participation levels. While never a complete substitute to meeting face-to-face, place-based tools for e-participation and co-participation, allow masses to effortlessly convey ideas about future development.

For planners, increased input levels mean more valuable information. A shift that opens new avenues for combating NIMBY problems in infill development and for, perhaps more importantly, creating cities for people.