India’s 2021 drone rules could be a deathblow to an already struggling industry

Government gazettes don’t typically make for riveting reads. The documents run into dozens and dozens of pages, you need to navigate through a ton of jargon and legalese, and there’s a lot of going back and forth involved – because the penalty for ‘contravention of sub-rule (1) of rule 23’ would suddenly manifest 20 pages later without a link back to the original rule.

Government gazettes rarely make for riveting reads, except when they come in the form of a notification from India’s Ministry of Civil Aviation, detailing the 2021 rules for the drone industry. Because here, clause after clause is designed to make your jaw drop. The more you read, the more you are gripped – by the sheer implausibility of it all.

Related: Thinking of importing or manufacturing drones in India? Read this first

The rules came into force the same day they were published in the Official Gazette – March 12, 2021. And just as simply as Thanos could set off mass extinction with a snap of his fingers, these rules deemed the entire drone industry in India illegal.

To be fair, much of the operations were being done furtively before March 12 also – chiefly because the government’s online platform designed to grant flight permissions and ensure the smooth functioning of all drone-related activities has been perpetually under construction. Only now, the unlawfulness of drone operations will attract much more severe penalties – not just for the owners, operators (commercial and recreational alike), service providers but also for the manufacturers, importers, and traders.

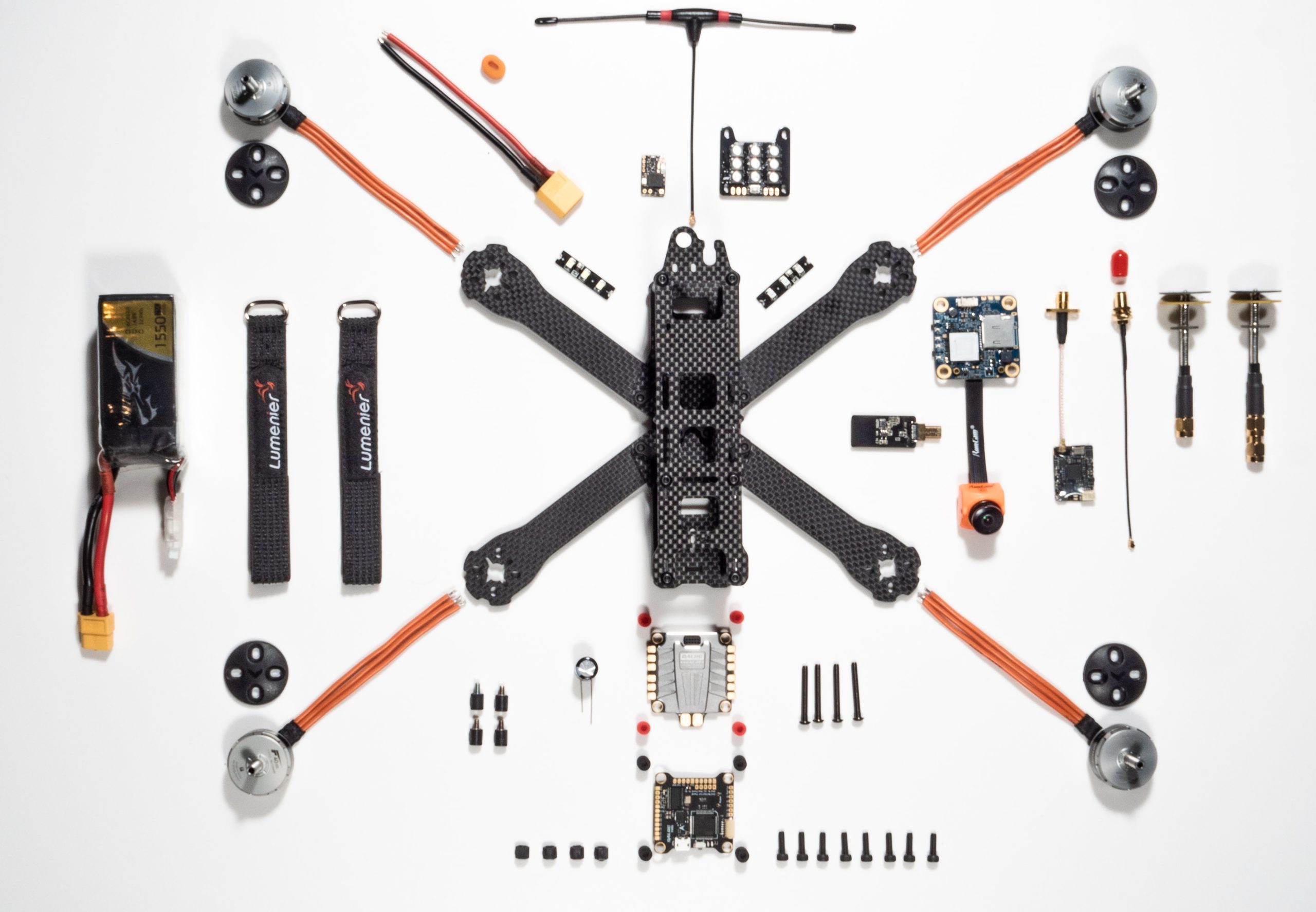

As per the Unmanned Aircraft System Rules, 2021, every stakeholder of the industry needs to procure an official certificate of ‘authorization’ from the Directorate General of Civil Aviation (DGCA) to continue doing what they may have been doing for years now – right from manufacturing the simplest of drone components, such as a wire or a screw, to conducting research and development of an unmanned aircraft system. And this is just the first step. The new rules are deliriously high on the licensing system.

Once you have received your ‘authorization’ certificate, you need to submit a separate application to the DGCA to obtain permission for the manufacture or import of a prototype drone (for a fee, of course. There’s a fee to be paid with every application). Each prototype drone that you create or import will be assigned a unique identification number by the DGCA. Hold on to these UINs, because their transfer from one stakeholder to another will also entail a time-consuming paper trail and fee at each step.

Now, to obtain a certificate of manufacture and airworthiness, you send another application to the DGCA, post which you handover your prototype drone and all the design documents to an ‘authorized’ testing laboratory chosen by the Director-General.

And then, you wait. Maybe for weeks, maybe for months. The rules don’t specify any timeline or tracking mechanism for the progress of any of these applications.

What they do specify is that if you need to import a spare part for a drone for which a certificate of manufacture and airworthiness has already been granted to you, you still need to take prior approval of the DGCA by filling out yet another application form. And no, it doesn’t help that the Directorate General of Foreign Trade has already issued you an Importer-Exporter Code (IEC) number.

By now, you should have understood that a passion for seeking approvals is a skill you must be able to highlight on your resumé if you are to survive in the Indian drone industry. So, before each test flight, you take prior clearance from the local authority and the Air Traffic Control – even when these test flights are to be conducted under the direct supervision of an appropriately licensed remote pilot at a predesignated site notified by the Central Government.

Also read: Flying a drone in India? See what 2021 drone rules say for pilots

That said, chances are, you may never reach the test flight stage. It would take nothing short of a miracle for you to find ‘authorized’ manufacturers for all the components the DGCA says your drone must have before it makes its way to a testing laboratory.

And by the time you check off the boxes on the list of the technical requirements, your drone would have become economically unfeasible for today’s markets.

A 360-degree collision avoidance system, for example, has been mandated for a Micro category drone (weighing ≤ 2 kg) that would be flown by a trained, ‘authorized’ operator within the visual line of sight. And an emergency recovery system is absolutely essential for a Small category (weighing ≤ 25 kg) agricultural spraying drone that has been designed to fly only 2 meters above the ground level.

Even toy drones (weighing less than 250 gm) are to be outfitted with Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) receivers and have high-tech features like geofencing capabilities and autonomous ‘Return to Home’ options.

For a hobbyist, however, the higher price point for a beginner drone will not be the only barrier to entry. To fly any drone weighing more than 250 gm for recreational purposes, you are required to undergo a week-long training program costing upward of INR 25,000. Two separate pilot permit applications need to be submitted to the DGCA – first as a student and then, after the completion of the training, as an operator. Two other applications must be submitted to get both the drone and the drone owner registered with the authorities.

And even after all this, you cannot just wake up one morning in a hotel and decide to capture your vacation moments from the air. Here also, you need to take prior permission from the DGCA, defining clearly the area where you want to fly. And how do you take this permission? Through the same defunct online portal, of course!

Interestingly, India is part of Joint Authorities for Rulemaking of Unmanned Systems (JARUS), a group of experts from National Aviation Authorities (NAAs) of five continents, EUROCONTROL, and the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA). In 2019, JARUS published a document – debated and developed over a period of 4 years – to recommend the level of regulatory involvement for various types of drones and drone operations.

This document suggested that based on the unmitigated risk associated with UAS operations, every drone and drone operation should be characterized by one of the following three categories:

Category A (Open)

In this category, JARUS recommends self-certification. Adoption of industry standards may apply but airworthiness requirements should not be made mandatory. Risk mitigation should be applied through the adoption of operational limitations, such as no-fly zones and visual line of sight operations, without requiring approvals issued by an aviation regulator. The operator should be deemed responsible for safe operations.

Examples of operations falling in this category include toy/Nano drones as well as recreational, hobbyist drones of the Micro category. This category could also include commercial drone operations that present a low unmitigated risk, such as low airspace survey of critical infrastructure located far away from human habitation.

Category B (Specific)

As the operations go beyond the limitations of Category A, an acceptable level of risk is ensured by a risk assessment of the operation and identification of mitigation steps. This could include requirements addressing the design of the drone, operational limitations, and qualifications of the drone pilot. Varying levels of oversight are recommended for this category.

Category C (Certified)

This is the category that should have full regulatory oversight because the high levels of risks here cannot be solely mitigated through operational limitations. As such, risk mitigation here would involve a type design approval (Type Certification), a certificate of airworthiness, flight manuals, instructions for continued airworthiness (maintenance), production approvals, and other associated certificates of traditional civil aviation.

India’s 2021 drone rules, it would appear, group all drones and drone operations under Category C. This, when JARUS bluntly provides multiple reasons for having a provision for Category A. Some of the reasons why JARUS members feel Category A self-regulation is important for the growth of the drone ecosystem include:

- Experience in various countries has shown that such a regulatory concept can ensure safety in an effective and efficient manner.

- The classic approach to aviation regulation, even if adapted in a very light manner, would most probably be too burdensome, because aviation authorities are inherently not fit for this task.

- Burdensome and disproportional regulation would most probably lead to the development of illegal operations due to difficulties in enforcement.

To be fair to DGCA, mandating geofencing is something that JARUS also recommends. But their report is quick to clarify that “in keeping with the overall concept of Category A, this technology should be available at a reasonable cost as well as easy to implement. This should be considered when determining if geofencing should be mandated for all drones or just to a subset depending on size or weight.”

India’s first Civil Aviation Requirements (CAR) for drones came out in 2018. It took the drone industry nearly two years after that to reach a stage where a handful of UAS companies could enjoy exemptions granted by government ministries and departments to conduct operations – primarily due to urgent demands presented by global issues like the COVID-19 outbreak and locust infestation. To date, the government’s ambitious online platform for monitoring drone operations, Digital Sky, is inoperative.

Now, the industry is in consensus that the new rules will make compliance virtually impossible, and as such, any drone company that does not have explicit exemptions from the government to do business in India can be penalized – and penalized heavily – at any moment.

Industry insiders and lobby groups, who have been continually engaging with the DGCA for amendments and improvements to the 2018 rules, feel that they have been grossly sidelined by the government. The problem is not only that their suggestions have been ignored by the DGCA but also that several more layers of operational complexities have been added through the new rules. By incorporating a multi-level, multi-license system, the ease of doing business has been impacted adversely even further.

Aviation Ministry officials have been vocal about their vision to make India the “drone capital of the world”. It is truly regretful that we seem to be moving in the opposite direction.

Time to assemble the Avengers? Join the discussion on LinkedIn.

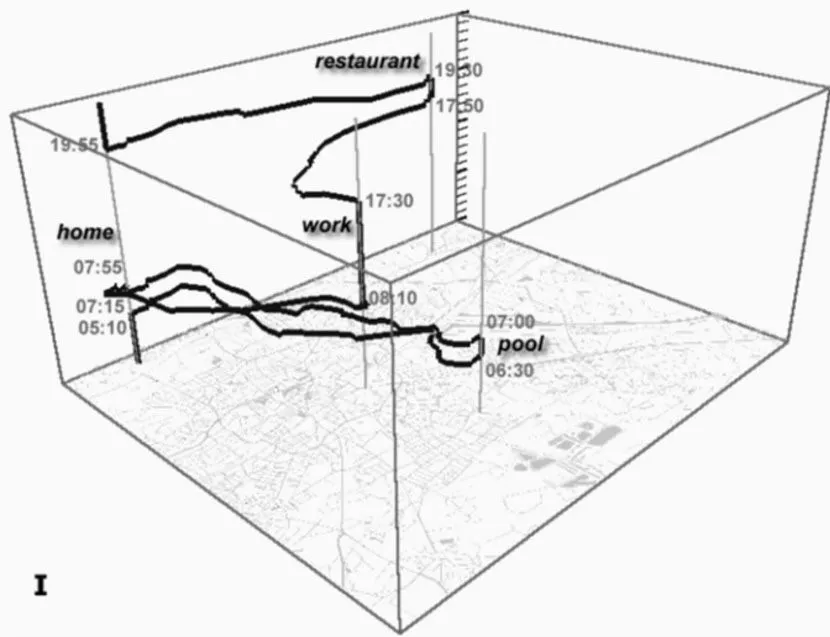

One of the analysis methods for visualization of simple 4D datasets is by using so-called space-time cubes, where the x and y planes represent the spatial aspect of the data while time is modelled onto the z-axis. With these, you can perform a simple visual exploration of those data sets with limited movement: If you only see a vertical line, it’s easy to tell that there is no change in the x and y dimensions, and therefore the object is stationary.

One of the analysis methods for visualization of simple 4D datasets is by using so-called space-time cubes, where the x and y planes represent the spatial aspect of the data while time is modelled onto the z-axis. With these, you can perform a simple visual exploration of those data sets with limited movement: If you only see a vertical line, it’s easy to tell that there is no change in the x and y dimensions, and therefore the object is stationary.