First ever global map of bee species blooms conservation hopes

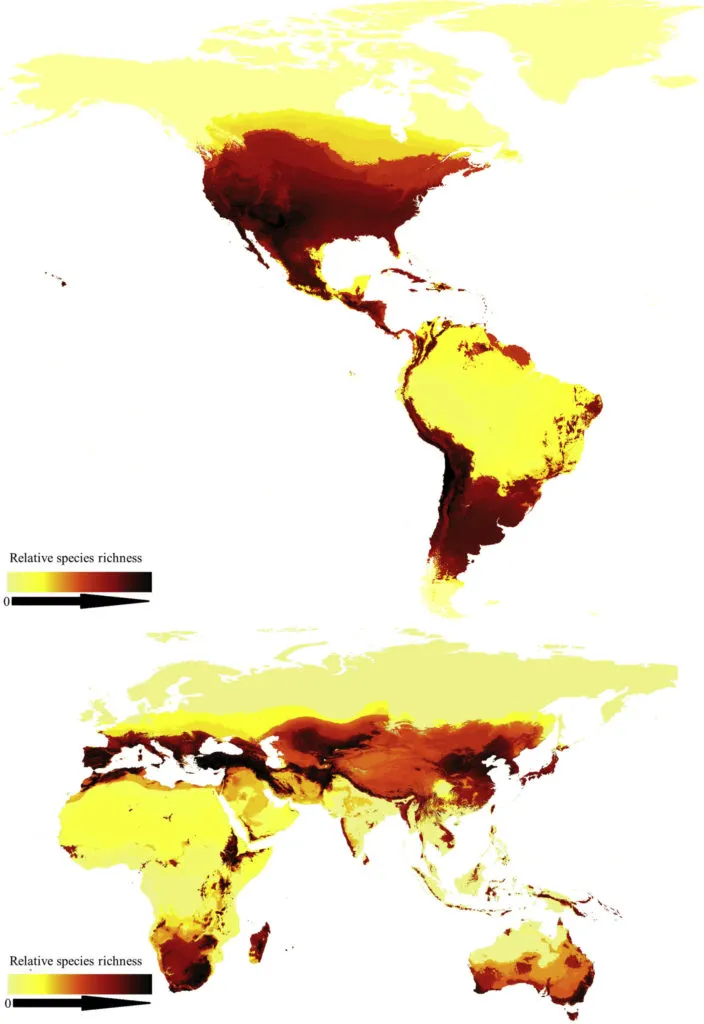

After analyzing almost 6 million public bee occurrence records, researchers are now ready to tell us where all the bees are! For the first time ever, a global map of bee diversity has been created to help in the conservation of these invertebrates as ecologically and economically invaluable universal pollinators.

We already know there are more than 20,000 bee species spread across the world. And as is the case with most plants and animals, it has always been expected that bees also follow a pattern called latitudinal gradient – wherein species tend to concentrate more toward the tropics and less toward the poles.

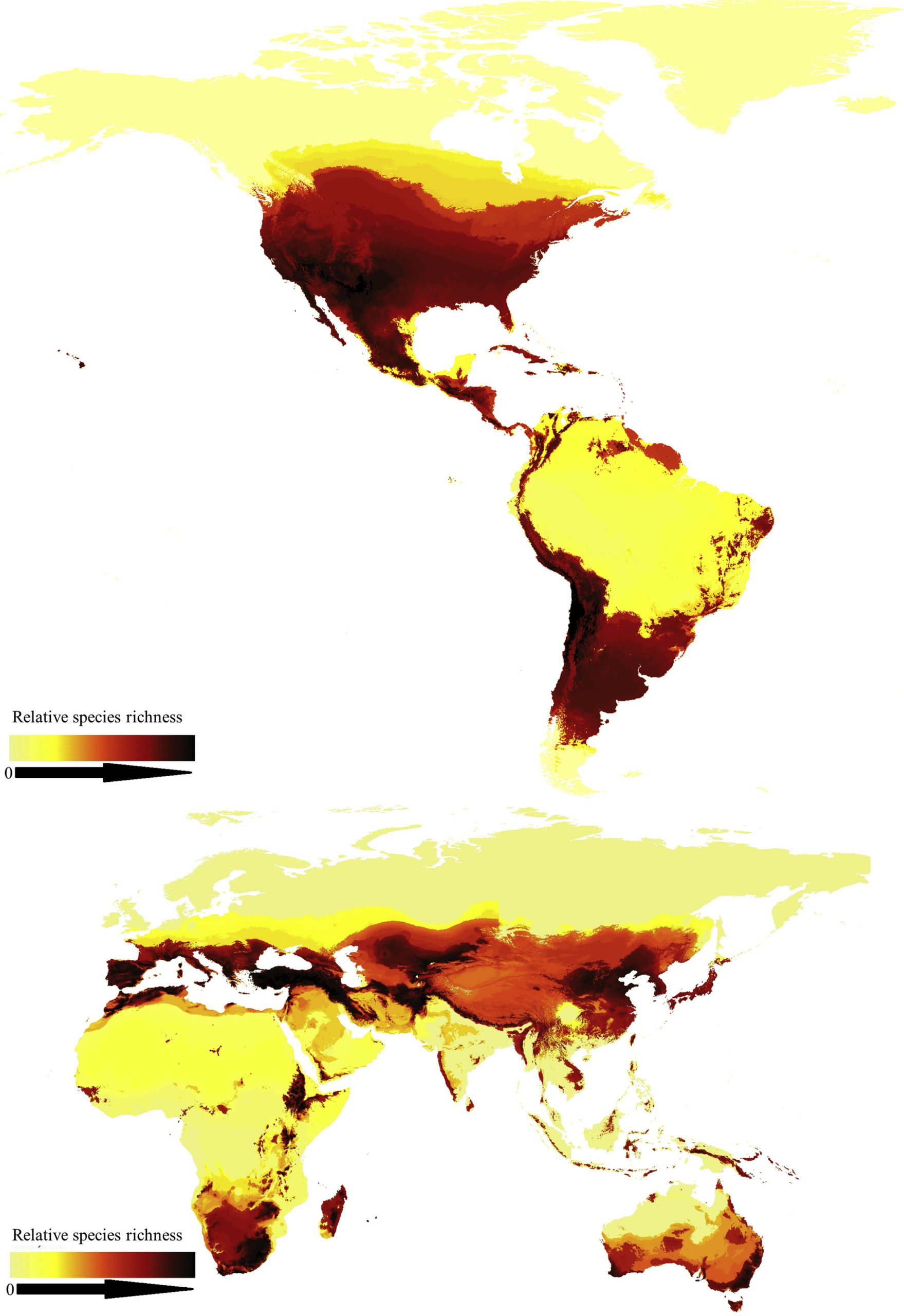

Turns out, bees are not a fan of general conventions. “The United States has by far the most species of bees, but there are also vast areas of the African continent and the Middle East which have high levels of undiscovered diversity, more than in tropical areas,” says John Ascher, senior author of the bee study published in Current Biology. Take a look at the map below:

Courtesy: Current Biology

The reason why there are far fewer bee species in forests and jungles than in arid desert environments is because trees tend to provide fewer sources of food for bees than low-lying plants and flowers. On the other hand, rains in the desert often lead to unpredictable mass blooms that literally carpet the entire area, providing bees with abundant food and nesting choices.

Building and sharing the knowledge of insect distribution is one of the biggest, most important challenges that biologists and conservationists face today. And Ascher, who is an assistant professor of biological sciences at the National University of Singapore, believes that the abundance of bee species cannot be interpreted in a large-scale analysis of distribution and potential declines of bee populations “until we understand species richness and geographic patterns.”

This is what makes this study particularly important.

“Many crops, especially in developing countries, rely on native bee species, not honey bees,” explains Alice Hughes, an associate professor of conservation biology and one of the authors of the study. “There isn’t nearly enough data out there about them, and providing a sensible baseline and analyzing it in a sensible way is essential if we’re going to maintain both biodiversity and also the services these species provide in the future.”