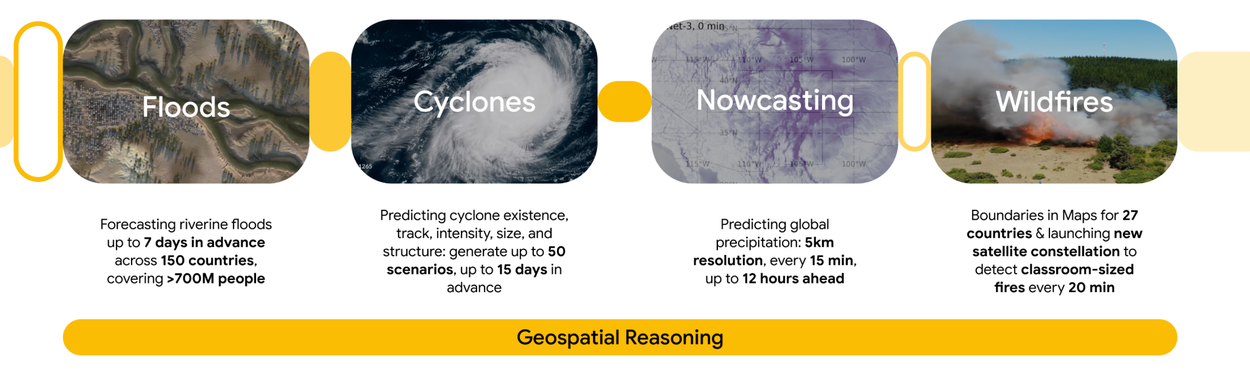

Modern geospatial AI has become remarkably good at prediction. Given enough historical data, models can forecast flood extents, traffic congestion, or infrastructure stress with impressive accuracy. Recent advances, such as Prediction-to-Map flood forecasting, show that complex spatial predictions can now be produced far faster than traditional numerical models.

Yet accuracy alone often fails at the moment decisions matter. When conditions change, planners and responders ask questions that predictive models struggle to answer. Why did flooding concentrate here instead of there? If we block this road or close that floodgate, what breaks downstream? Is a certain outcome even physically possible given the constraints of the system?

This gap has become increasingly visible during recent extreme events, where cascading infrastructure failures revealed that many breakdowns were not caused by missing predictions, but by poor understanding of dependencies and constraints. As several analyses of modern infrastructure risk point out, models trained on past patterns often struggle when the rules of the system are stressed or altered.

This article argues that spatial systems require more than learning patterns from data. They require geospatial reasoning: the ability to respect physical constraints, understand connectivity, and reason about “what if” scenarios. It is written for geospatial practitioners, data scientists, and planners who already use GeoAI, but want to understand where learning ends, where reasoning begins, and why combining both is essential for real-world decision support.

What Geospatial Learning Does Well?

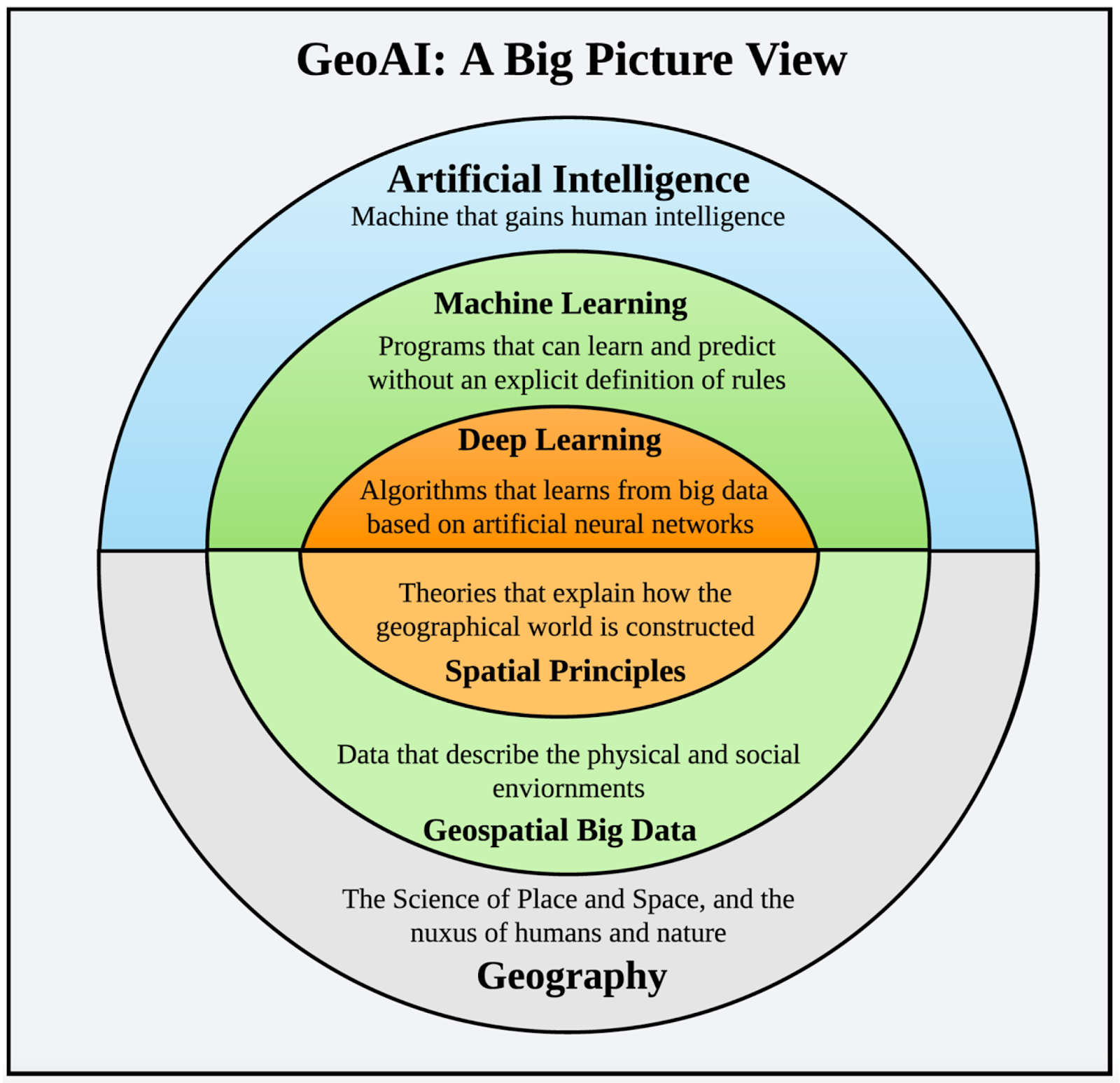

Modern geospatial learning is strong at large-scale pattern recognition. By processing vast amounts of satellite imagery and sensor data, GeoAI systems can extract building footprints, classify land cover, detect vegetation stress, and monitor change at a global scale.

A major advance has been the rise of geospatial foundation models, trained on diverse Earth observation data to generalize across tasks and regions. These models can segment complex scenes, describe imagery, and adapt to new problems with minimal additional training, even in data-sparse settings.

Learning also excels at creating spatial embeddings, compact representations that allow places to be compared, clustered, or searched for similarity. Work on satellite embeddings and large-scale spatial representations shows how embeddings make it possible to compare places, search for similarity, detect anomalies, and transfer insights across cities, ecosystems, and countries

Together, these capabilities have lowered the cost of turning raw geospatial data into useful signals. Learning gives us powerful eyes on the planet. The question is where this approach begins to break down.

Source: MDPI

Where Learning Falls Short?

Learning can estimate what is likely. Reasoning determines what is possible.

As spatial systems grow more complex, the gap between recognizing patterns and understanding mechanisms becomes clear. A core limitation of geospatial learning is its reliance on correlation without awareness of physical constraints. Models may associate flooding with certain visual patterns in imagery, yet fail when terrain, vegetation, or flow dynamics differ from the training data, a weakness widely discussed in analyses of the limits of AI in water resource management.

This issue appears clearly in flood modeling. Evaluations of AI-enhanced versions of the National Water Model show that while learning can improve accuracy, models that ignore dominant physical processes systematically underpredict flooding when conditions shift.

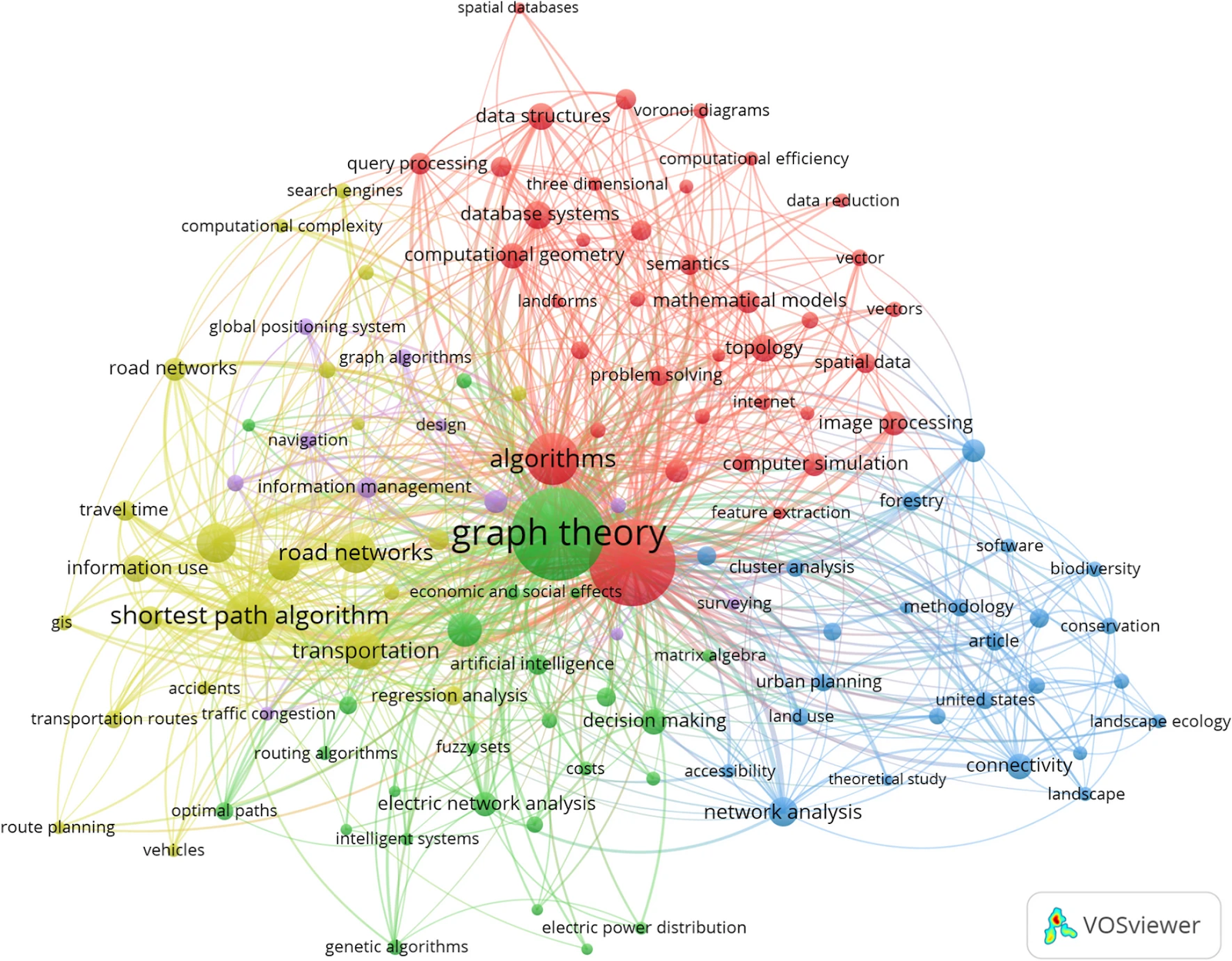

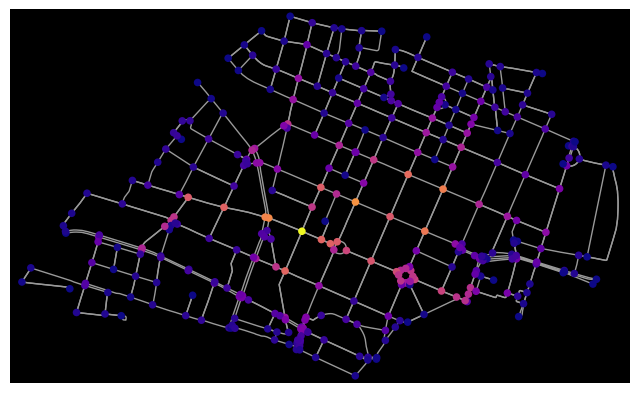

Learning also struggles with topology and connectivity. Geography is governed by networks, yet many models treat spatial data as independent pixels. This leads to failures when disruptions propagate through systems, a problem documented in studies of spatial reasoning errors in AI and benchmarks on LLM spatial reasoning.

Finally, purely data-driven models lack counterfactual reasoning. They extrapolate from the past but struggle to assess interventions that change the system itself. Research on causal machine learning for flood damage estimation shows why prediction alone is insufficient in rapidly changing environments.

Learning can estimate what is likely. Reasoning determines what is possible.

What Geospatial Reasoning Actually Means?

If geospatial learning provides the eyes of a system, geospatial reasoning is the brain. It takes detected patterns and evaluates them against rules about how the physical world works. Instead of stopping at “there is a road here,” reasoning asks whether that road is the only access to a hospital, or what happens if it is blocked.

At its core, geospatial reasoning is a shift from statistical guessing to structural thinking.

First, it respects rules and constraints. Certain constraints are non-negotiable: water flows downhill, vehicles cannot pass through solid barriers, and land uses cannot overlap arbitrarily. Many failures in AI systems stem from violating these basic physical truths, a limitation highlighted in analyses of why AI struggles with real-world physical tasks.

Second, reasoning focuses on relationships rather than isolated features. Geographic entities exist within hierarchies and systems. A drain belongs to a pipe network, which sits inside a watershed. This relational view underpins the concept of geospatial knowledge graphs.

Third, geospatial reasoning propagates effects through space and time. A failure rarely stays local. If a substation goes down, reasoning traces which neighborhoods or services depend on that connection, reflecting the logic of flow and dependency that defines spatial systems.

Finally, reasoning enables “what if” and “what must be true” questions. Instead of predicting what usually happens, it evaluates interventions and constraints. This shift toward scenario-based reasoning is increasingly emphasized in work on geospatial reasoning with foundation models.

Learning helps AI recognize the pieces on the board. Geospatial reasoning gives it the rulebook to understand the consequences of each move.

Source: Google Research

Why Geography Demands Reasoning?

Geography is fundamentally different from most data domains. While many datasets treat records as independent, spatial systems are defined by proximity, flow, and dependency. This makes purely predictive models fragile when applied across regions or scales, a limitation highlighted in work on spatial generalization in machine learning.

This difference comes from a few core spatial properties. Geographic systems are shaped by two factors: connectivity, as roads, rivers, and power lines form networks whose effects propagate, and directionality and flow, as physical rules like gravity constrain what is possible. Ignoring these constraints is a common source of error in hydraulic and infrastructure modeling, as shown in examples of common mistakes in hydraulic models. Geography also exhibits spatial dependence, where the state of a place is influenced by its surroundings, a foundational concept in spatial topology and relationships.

Because of these properties, geographic systems behave as systems of systems. Without explicit reasoning about structure, constraints, and relationships, prediction alone is not enough.

The Role of Graphs and Data Cubes

To bring geospatial reasoning into practice, two data structures matter most: graphs and spatial data cubes. Graphs encode relationships explicitly, treating buildings, roads, pipes, and substations as connected entities rather than isolated features, which allows systems to trace dependencies and understand how effects propagate through networks. Spatial data cubes add time to this picture by stacking maps across days, months, or years, preserving how places evolve instead of freezing them in a single snapshot. Together, these structures align digital representations with how the physical world actually works, enabling reasoning about connectivity, change, and consequence rather than relying on opaque predictions.

Where Geospatial Reasoning Matters Today?

Geospatial reasoning is already changing how high-stakes decisions are made, especially in areas where static maps are no longer sufficient.

In the insurance industry, reasoning is replacing one-size-fits-all hazard zones with contextual risk assessment. Instead of pricing risk solely on whether a property falls inside a flood or wildfire boundary, insurers increasingly use geospatial data for insurance to account for proximity, elevation, directionality, and mitigation. This allows underwriting to reflect local conditions, such as drainage improvements or reduced exposure to wind-driven fire paths, a shift already reshaping pricing and portfolio management, as described in how geospatial analytics is changing insurance.

Geospatial reasoning is also central to climate adaptation planning. Rather than planning for average conditions, cities increasingly plan for threshold scenarios, using adaptation playbooks to link physical changes like sea-level rise or extreme heat to concrete actions. This approach, reflected in climate adaptation playbooks and broader assessments of adaptation costs and strategies, enables proactive rather than reactive decisions.

In these domains, geospatial reasoning does more than refine predictions. It connects spatial data directly to action.

Source: Google Research

From Predictive Maps to Decision Support

Geospatial AI is shifting from producing predictions to supporting decisions. For years, the goal was to answer “what is likely?”, resulting in maps that forecast risk or change. Today, decision-makers increasingly need systems that help answer a different question: “What should we do?”

This is where geospatial reasoning sits on top of learning. Learning extracts patterns from vast datasets. Reasoning evaluates those patterns against constraints, dependencies, and consequences, turning predictions into guidance that can actually be acted upon. The emphasis moves away from interpreting probability surfaces and toward evaluating options, trade-offs, and outcomes.

Looking ahead, the future of GeoAI is not about replacing learning, but grounding it. Learning will remain the eyes of the system, detecting patterns at scale. What comes next is grounded intelligence: models that combine data-driven learning with physical rules, topology, and causal structure, allowing systems to reason about what is possible, not just what is likely.

As these systems mature, geospatial reasoning will also become more accessible. Natural-language interfaces and agentic GIS tools are lowering the barrier between spatial expertise and action, enabling more people to ask meaningful “what if” questions and receive transparent, explainable answers.

Learning gives us vision. Reasoning gives us judgment. Together, they are what will make GeoAI truly useful in the real world.

Further Resources

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g9F-_tCakL8&t=1s

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZyH3-7pBBiQ&t=1s

- https://medium.com/@guneetmutreja/beyond-pixels-a-new-era-of-geospatial-reasoning-with-alphaearths-embedding-calculus-6dcf073db057

- https://arxiv.org/abs/2505.17136

Did you like this post? Read more and subscribe to our monthly newsletter!