Understanding The Earth Observation Value Chain

Editor’s note: This article was written as part of EO Hub – a journalistic collaboration between UP42 and Geoawesome. Created for policymakers, decision-makers, geospatial experts and enthusiasts alike, EO Hub is a key resource for anyone trying to understand how Earth observation is transforming our world. Read more about EO Hub here.

Ever since the Explorer 6 satellite captured the first image of Earth in 1959, organizations have been finding ways to exploit and add value to Earth Observation (EO) data. Although still described as ‘emerging’, the sector has seen significant growth in recent years, and is now a booming market, with EO data being used to monitor land, sea and atmospheric factors; and finding numerous applications, from agriculture and the environment to logistics and security.

Explorer 6 — photo from NASA

The market is expected to grow even more rapidly over the coming decades, in part due to recent technological breakthroughs regarding data collection and storage, as well as new business models, including online data marketplaces and cloud infrastructure to process data. However, the single most important factor has been unlocking the bottleneck right at the beginning of the EO ‘value chain’: the initial cost of launching a satellite into space.

Understanding the EO value chain is critical in providing context, from explaining how the industry got to where it is today to predict where it is headed next.

Defining the Earth Observation value chain

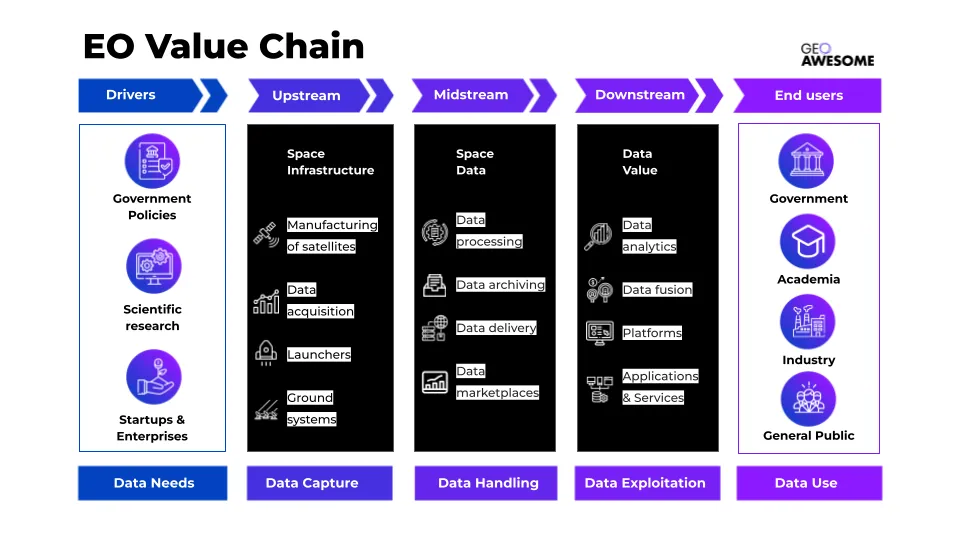

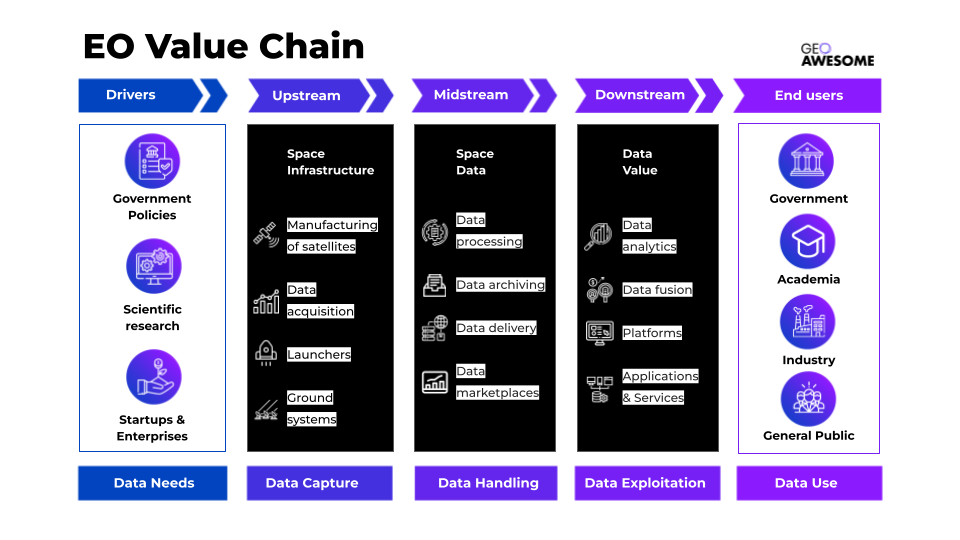

When it comes to the EO industry itself, the core value chain can be divided into three main segments: upstream, midstream and downstream.

The upstream component encompasses data capture. In practice, it refers to the manufacturing and operation of satellites, also covering the launch and ground systems and any other relevant space infrastructure.

The EO midstream is all about data handling. This effectively means how data is received by the ground infrastructure, then how it is stored, pre-processed, catalogued and archived. Midstream also involves data distribution and delivery through EO marketplaces like UP42, among others.

Downstream is where data is exploited—or, in other words, has value added to it, by being processed and converted into products, applications and services. This involves big data and analytics, and will often mean integration with other sources of data.

To paint the full picture, we should also include initial drivers and end users. The market is driven by scientific analysis and R&D, as well as government policies and the mandates of individual agencies and departments. End users at the end of the chain are critical elements, as they are generating the demand for the sector to grow in the first place. In recent years, we are seeing an interesting shift. It is no longer the reserve of the military and science; we are now seeing governments, academia, industry and even the general public as customers for EO products.

The evolution of the Earth Observation value chain

We are currently witnessing a rapid evolution of the EO value chain, with three main drivers: broad technological development, an increasing need to monetize that technology beyond its traditional applications in the military and government, and the entrance of new players into the market.

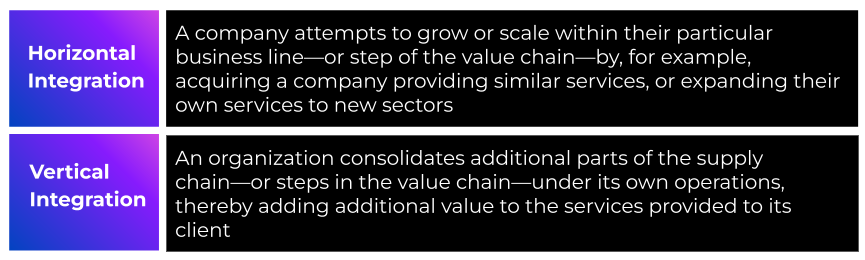

As a result, there are currently multiple examples of both horizontal and vertical integration occurring in the EO market. Understanding where and why this is happening plays a major role in analyzing how the EO sector operates and where its future lies.

Downstream, there has been an explosion in the number of independent startups who are providing niche data analytics services; partnering with large satellite operators or marketplaces to access their enormous archives and then processing the data for clients. Many of these, like LiveEO, Orbital Insights, and Satelligence, are integrating horizontally as they expand their offering to new sectors. Orbital, for instance, now focuses on retail, finance, insurance and defense

Upstream, on the other hand, many satellite manufacturers are in the process of vertical integration. In theory, the aim is to simplify the way that clients purchase, extract, and leverage their data, but from a business point of view it’s about capturing a higher share of value. Planet, for example, is expanding its data processing and analytics capacities with the hope of adding both value and differentiation to its offering, by providing basic tools including change detection, object classification, and more. Another example is Maxar. Back in 2016 the satellite data giant acquired geospatial analytics company Radiant Group, with the aim of strengthening their presence in the intelligence field, especially in the US.

Some large incumbents are integrating both vertically and horizontally. For example, since the early 2000s, Airbus has been investing in the development of the Farmstar platform to capture the agricultural market. In doing this, Airbus is expanding their offering across the value chain right the way to the downstream, by creating software which enables end clients to easily access and analyze the data from their Pleaides and SPOT constellations. At the same time the company has been involved in multiple SAR and optical satellite projects.

Vertical integration is currently the topic of much discussion within the industry. It certainly has advantages, creating customer loyalty and providing the end client with easy access to data. It can also be cost-effective:

However, for the industry more broadly, there are also downsides to vertical integration. There is an argument that satellite manufacturers, for example, should focus on their core business offering of data capture and allow other companies to create solutions which add value. If a satellite operator provides additional services, it is able to offer the data itself at a discounted price, whereas a startup has less flexibility, as it needs to buy the data and then offer analytics on top.

By incorporating data analytics, satellite manufacturers tend to close down opportunities, blocking the market for new entrants and, in a way, cannibalizing their own market. Additionally, from a customer point of view, buying data directly from the satellite operator is likely to restrict clients to a given ecosystem of data and solutions rather than giving them the flexibility of choice.

The importance of the midstream

The midstream has the potential to provide balance to the EO value chain: Marketplaces and data handling solutions provide a service to the upstream value chain players (the satellite operators) by expanding the market for their data, whilst also serving the downstream value chain by making the data more affordable, accessible and practical, so downstream companies can build their own solutions for clients.

Open access programs—like the EU’s Copernicus and NASA’s Landsat—have made EO data freely available to both end users and downstream operators. However, the data from these programs is only of low–medium resolution, and it, therefore, has limited applications. EO data marketplaces like UP42, on the other hand, provide access to high-resolution data, as well as the infrastructure and capacity to process and analyze it.

Marketplaces such as UP42 integrate multiple data providers, including Airbus, Capella Space, and more. This ensures that clients are not limited to a single vendor but are able to take advantage of whichever provider best suits their requirements—adding huge value when it comes to analysis of the data. UP42 is also integrated with Esri, and other significant geospatial software providers; this increase in advanced analytical service integrations will also provide huge value to end users.

This data democratization enables companies across the value chain to expand horizontally; it allows satellite companies to focus on making the best satellites and win the market by having the best data, and allows startups and companies that build data solutions and analytics to do just that, rather than spending energy on solving problems around access to data and data processing. As a result, it accelerates innovation—which in turn brings significant growth to the whole industry.

Satellite image from UP42 platform

Big Tech and EO

One more major development that shouldn’t be overlooked isthe arrival of Big Tech on the EO scene. Digital titans like Amazon (with Amazon AWS) and Google (Google Cloud) began by offering data storage and cloud computing services to players at every stage of the value chain, and are now investing in additional functionalities.

In partnership with Capella Space, Amazon has launched AWS Ground Station, a service which enables clients to “control satellite communications, process data and scale operations”, all without the hassle of creating their own ground station infrastructure.

Google, meanwhile, has been integrating vertically in both directions, investing in satellites and providing data to end users: Having recently acquired an equity stake in Planet, the digital giant has now also secured a multi-year deal to buy EO data from Planet for use in its own services, including Google Maps and Google Earth Engine.

A collaborative ecosystem for a better future

The role already played by Earth Observation data in our society cannot be underestimated, but there is still tremendous opportunity for improvement.

When it comes to EO data, each segment of the value chain (upstream, midstream, and downstream) brings the information held within the data closer to its end user. A value chain perspective is hugely useful in recognizing the interconnectivity of different parts of the EO ecosystem—it helps define how individual pieces of the industry fit into the larger whole.

There is an increasing availability of EO data and processing infrastructure, not only provided by satellite companies themselves but also by marketplaces like UP42 and tech giants including Google. A healthy ecosystem is essential in providing an environment where new entrants can explore new ways to harness the power of EO data. Through collaboration, horizontal integration, and fostering interoperability, access to data can become even more widespread—and EO can thus play a critical role in helping humanity.

Did you like the article? Read more and subscribe to our monthly newsletter!