Beyond NDVI: What are vegetation indices, and how are they used in precision farming?

Editor’s note: This article was written as part of EO Hub – a journalistic collaboration between UP42 and Geoawesome. Created for policymakers, decision makers, geospatial experts and enthusiasts alike, EO Hub is a key resource for anyone trying to understand how Earth observation is transforming our world. Read more about EO Hub here.

Farmers and agronomists tend to be very practical, hands-on people. What they want, above all, is full awareness of the situation in their fields: are there any diseases affecting their plants? Are the plants sufficiently watered? Are they fertilizing effectively and efficiently? If a grower is dealing with an area covering dozens of hectares, it can be very difficult to keep track of the relevant details with field visits and ground sensors alone.

This is where vegetation indices come in. Vegetation indices are a remote sensing technique that can be used to identify vegetation and measure its health and vitality—and they are becoming an increasingly important parameter within crop development analytics, enabling analysis at a local, regional, country-wide or even global level. On the largest scale, vegetation indices may show global trends which can influence policy, inform global aid support and help to prepare for food supply challenges, whereas on the most localized level, they can provide detailed data for individual growers, to help better understand the health of specific parts of a field—or even specific plants.

How do vegetation indices work?

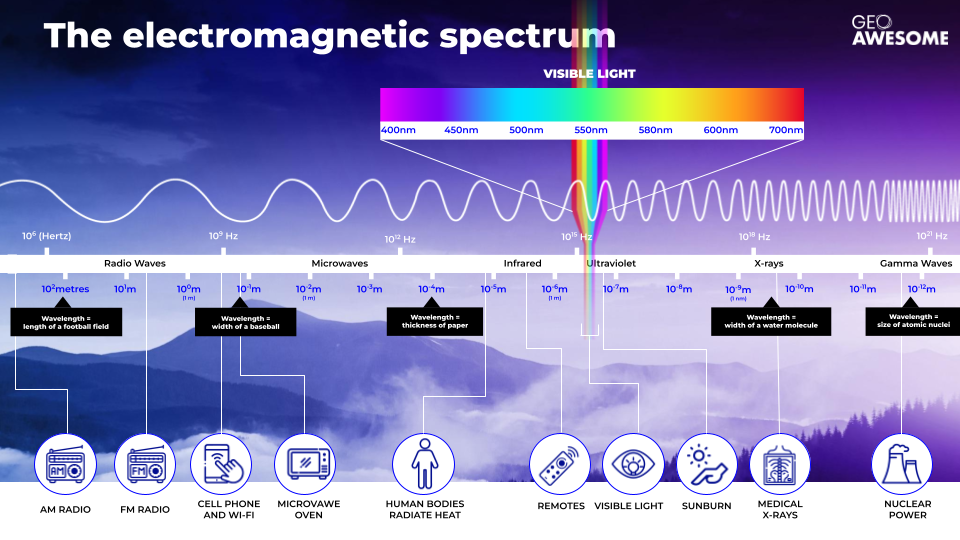

Visible light—the light that reflects off objects and enables us to see them with the human eye—is part of the electromagnetic spectrum; specifically, wavelengths between around 400–700nm. The wavelengths either side of visible light are ultraviolet (UV) and infrared rays.

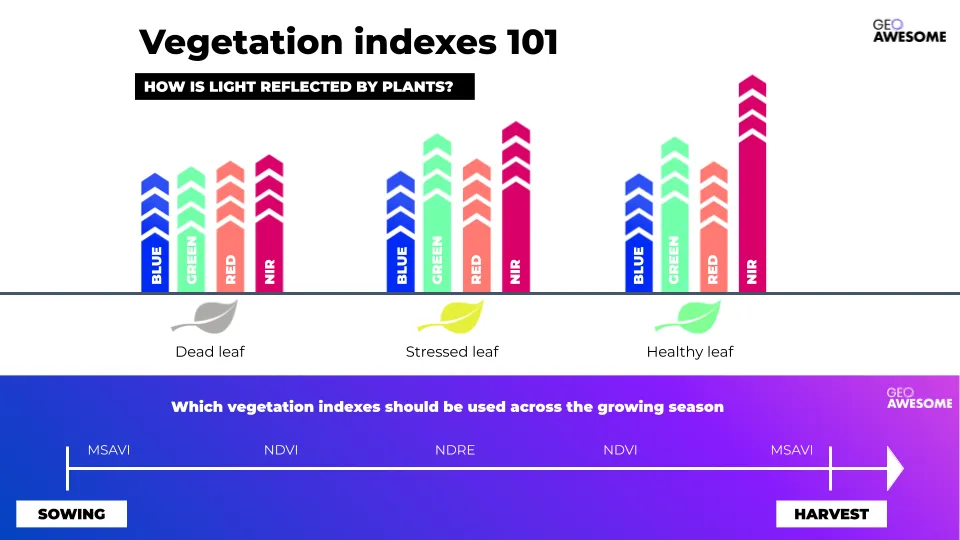

Plants absorb some of this light, and use it to grow, through the process of photosynthesis. Vegetation indices work by analyzing the light which is not absorbed, but instead reflected off the leaves, using this information to detect plantsand evaluate their condition. Broadly speaking, healthy plants (those rich in chlorophyll) reflect more near-infrared (NIR) and green light than those with stressed or dead leaves.

The concept itself is straightforward, and the output from vegetarian indices is relatively easy to interpret: typically, it will be presented in the form of a heatmap, where green color shows healthy vegetation and a red color indicates less healthy plants. This ease of use is one of the reasons that vegetation indices are so widely used in agriculture.

Did you like this article? Read more and subscribe to our monthly newsletter!

How do you like to article so far? Support our blog by subscribing to our monthly newsletter!

NDVI: A half-century of vegetation analysis

The best-known vegetation index is the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index, or NDVI. Developed in the 1970s, the technology takes advantage of what was at the time a breakthrough in earth observation data: the multispectral data provided by Landsat-1. Despite its 50-year history, NDVI has experienced a boom within the last decade, due to the increased availability of open satellite data—including the Sentinel constellation from 2014 onwards—together with the growing popularity of drone technology, combining to democratize earth observation.

Specifically, NDVI works by comparing red and NIR light to identify the amount of chlorophyll in leaves. Initially it was used simply to detect the presence of vegetation—and NDVI remains one of the most widely used indices for detecting plant canopies using remotely-sensed multispectral data—but the technology was quickly adopted to quantify ‘photosynthetic capacity’, a key indicator of plant health.

The primary disadvantage of NDVI is that the index reaches high ‘saturation’ relatively quickly—effectively, as soon as the field is covered by healthy, reflective leaves, the NDVI will be at a very high level. This naturally makes it a good indicator of plant health and biomass, but it lacks subtlety when it comes to warning signs early in the growing season and vegetation changes late in the season.

Beyond NDVI

Given the limitations of NDVI, and to avoid misinterpretation of results, online farming platforms provide agronomists with a wide range of other vegetation indices to complement NDVI. Some of the most popular ones include:

Modified Soil Adjusted Vegetation Index (MSAVI)

MSAVI is a variation on the Soil Adjusted Vegetation Index (SAVI). Both indexes are designed to mitigate the effects of soil on light analysis, making them more sensitive in circumstances where there is a high percentage of bare soil, scarce vegetation, or low chlorophyll content—all instances where NDVI struggles to provide accurate measurements. MSAVI is therefore most useful for monitoring crops in the first months following sowing.

Normalized Difference Red Edge (NDRE)

Another popular vegetation index, NDRE works by analyzing ‘red edge’ light—the narrow band of the visible light spectrum where red becomes NIR. It’s particularly sensitive to chlorophyll content, changes in leaf area, and the effect of soil in the background. It can measure the NIR light which has penetrated through to the lower part of the canopy, and is therefore ideal for analyzing the health and vigor of mid- and late-season crops, when the leaves have accumulated high levels of chlorophyll. NDRE can also be very helpful for determining the relative nitrogen content of crops, independent of the quantity of nitrogen in the soil.

Canopy Chlorophyll Content Index (CCCI)

CCCI analyzes the relative levels of reflected red, red edge, and NIR light, and is used to estimate the amount of nitrogen—a key component of chlorophyll. By correlating CCCI with tissue samples from crops, farmers are able to accurately estimate the nitrogen (N) variation of across a field. This method can provide information on N levels much earlier in the growing season than other indices, which helps growers to fertilize more precisely and efficiently.

Each vegetation index has a different sensitivity, and therefore they should be applied at different stages in the growth cycle: MSAVI is applied in early stages, when there is limited leaf coverage; NDVI during the period of rapid growth; then NDRE at later stages when leaf coverage is fuller. It can then be useful to return to NDVI and finally MSAVI again as foliage decreases and the crop transitions to ‘senescence’.

How do farmers use vegetation indices in practice?

The tools above are just a small sample of the many vegetation indices which can help farmers understand different parameters of crops or soil, including nitrogen variation, moisture levels, and more. Farmers can access and calculate these indices via farm management platforms, GIS tools, or satellite data and algorithm marketplaces such as UP42, where multiple complex vegetation indices such as NDVI, NDWI (Normalized Difference Water Index) EVI, and MSI (Moisture Stress Index) are all available.

However, the increasing popularity of vegetation indices can also lead to a misconception that reflectance values are the definitive measure of vegetation health. This is not the case, and researchers are keen to point out that a vegetation index is a qualitative measurement, rather than a quantitative one. Furthermore, a similar output may mean a completely different thing for two different fields.

Data-driven farms should therefore use multiple indices to analyze the performance of their crops through the season, and integration with other sources of data is key in avoiding misinterpretation. It’s only once these additional data layers are applied that the true meaning of a vegetation index can be understood. An example might be a field in which NDVI indicates underperformance in two separate areas. Without additional data, the assumption may be that the cause of this is the same in both areas. However, other data sources can reveal different issues, including erosion, moisture, or nutrient content.

Fortunately, farmers and agronomists are traditionally hugely risk-averse. They know that one poor decision can have devastating effects on yields. As a result, most agronomists—those who are progressive enough to use vegetation indices at all—will not implicitly trust the data on its own. They will verify the data in person, physically going to the field to inspect the areas, and overlaying the satellite data with other data layers including soil samples and elevation data.

Indeed, knowing how to interpret and apply the data is often more important than the type of camera used to capture it. And of course, vegetation indices do not eliminate the job of the agronomist, as the most important factor in interpreting the data is understanding the physiology of the plant itself. Vegetation indices are useless unless they are used by someone who understands the data, but also the plant, the soil, and the wider environment.

What’s next for vegetation indices?

Researchers, data scientists and agronomists are constantly searching for new formulas that can provide much needed information on crop performance. In some cases, farmers are even looking to create their own custom indices, and some companies already provide index calculators that meet this need. If someone has a thorough understanding of both the physiology of their plants and the data, they can customize an index to answer their specific questions.

There’s also potential to be mined in Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR). SAR is very well understood by the agriculture industry, and embraced for its ability to penetrate cloud cover, but currently it’s used on a fairly broad level. The fact that it can provide data from below leaf canopies holds great promise for more specific indices.

Finally, the drone industry can offer a different perspective, as the imagery is captured from closer to the ground, with fewer atmospheric factors to contend with. There is therefore less pre-processing and correction needed, and the image resolution is much higher, meaning drone data can potentially be used to more accurately calculate an ‘absolute’ reflectance value from which all the ‘relative’ indices are calculated. Additionally, centimetre level resolution means that it can be observed and calculated with much higher level of detail, even for an individual plant.

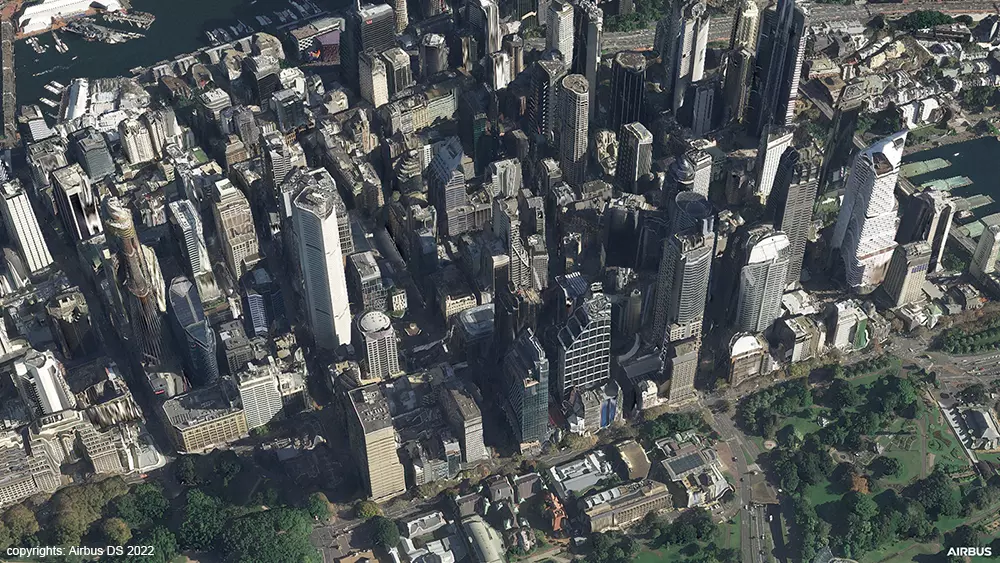

Interestingly, very-high resolution satellite data such as Pléiades Neo with 30cm GSD also opens a wide range of possibilities to analyze the conditions of individual plants. Such data are particularly useful for high-value crops like vineyards and olive orchards, which are now facing increasing challenges of drought, so farmers need to use water resources in a far more efficient way.

Combining this ultra-targeted information with more generic overview coming from open satellite imagery may well provide farmers with that perfect combination of data that they seek. Such scenarios are getting more and more feasible with the wide availability of open and commercial satellite data via easy to use marketplaces such as UP42.

Vegetation indices—a vital part of a modern, digitalized farm

There is a whole world of vegetation indices available to the agriculture industry, going way beyond NDVI. In practice, even regular RGB or true color maps will give an agronomist highly relevant information—and very often there is a clear correlation between NDVI and RGB data. Each additional data source can be another powerful instrument in the agronomist’s toolbox, helping them to make informed decisions on the farm.

However, vegetation indices are not absolute values; they are indicators of the health and condition of a plant. To truly understand the information, and to use it for more detailed analysis of crop performance, farmers should combine vegetation indices with other data layers, including elevation models and soil samples. And of course, to make the most effective use of vegetation indices, a farm needs to be operating digitally already—this means using farm management software, variable rate spraying machines, and digitalized processes across the board.