Creating Livable Spaces: Introducing the Walkability Index for Sustainable Mobility

Walkability is increasingly being recognized as essential element of healthier, more sustainable, and more livable communities. Given that the transport sector is one of the largest contributors to CO₂ emissions, and—with limited progress in reducing these emissions—promoting sustainable mobility has become an urgent priority. Walking and cycling are among the most efficient, low-impact modes of urban transportation, making their improvement essential for creating healthier, more livable cities. Furthermore, walkability is an important component of the “15-minute city” model, where essential services and amenities are accessible within a short walk from any point in the city.

What is Walkability?

Walkability refers to how friendly an area is to walking, influenced by factors such as pedestrian pathways, street safety, proximity of amenities (like benches or cafés), and the overall comfort and attractiveness of the walking environment. A walkable city encourages residents to choose walking over commuting by car, regardless of the season or time of day. This shift reduces carbon footprints, improves energy efficiency, and benefits public health. Walkability also brings economic and social advantages, such as increased business activity in walkable neighborhoods and active social interaction within the community.

Our Approach to Walkability

At the core of climate-friendly urban design is the need for practical, data-driven indicators that guide effective local action. HeiGIT, the Heidelberg Institute for Geoinformation Technology, addresses this need by developing indicators to support sustainable mobility and other urban climate action initiatives. These indicators help local stakeholders make informed decisions by visualizing key aspects of urban environments, from transportation options to patterns of land use, highlighting both community strengths and areas for improvement.

Recognizing that there is no universal approach to fostering urban mobility and reducing climate impact, HeiGIT tailors geospatial indicators to reflect the distinct walkability needs of each city. These tailored indicators enable urban planners, NGOs, and other stakeholders to address specific walkability challenges in their cities, factoring in unique cultural, environmental, and socio-economic conditions.

Using a co-creation process, we are building a walkability index that can adapt to diverse regions and contexts worldwide. Through a series of workshops, we identify which factors are most important to consider for walkability in that specific context. For example, in one city, sidewalk availability and safety might be top priorities, while in another, factors such as air quality or accessibility might take precedence. These factors can range from the presence of benches and rest areas, to the condition of surfaces and the level of traffic. Other indicators, like the proximity of essential services or the extent of lighting, may also play a critical role in enhancing walkability.

This adaptable approach is exemplified in cities like Lagos, Nigeria. Here, despite the lack of formal sidewalks, low car traffic allows pedestrians to walk comfortably on the main streets. This phenomenon is far from unique. In many parts of the world, areas with very low car traffic naturally become walkable, even without traditional sidewalks. Such contexts challenge conventional definitions of walkability and demonstrate the importance of considering local conditions when assessing what makes an environment “walkable.”

Methodology and Data Collection

We are working on a walkability index that will be globally accessible but locally adaptable, leveraging open data and additional tools. OpenStreetMap (OSM) is our primary data source, providing detailed information about urban transportation infrastructure and its properties. This crowdsourced, open-access data enables diverse cities to incorporate walkability into urban planning and design, ensuring that each city’s unique landscape and requirements are met.

We currently have developed three separate indicators that use OSM data to assess different aspects that influence how walkable streets and paths are.

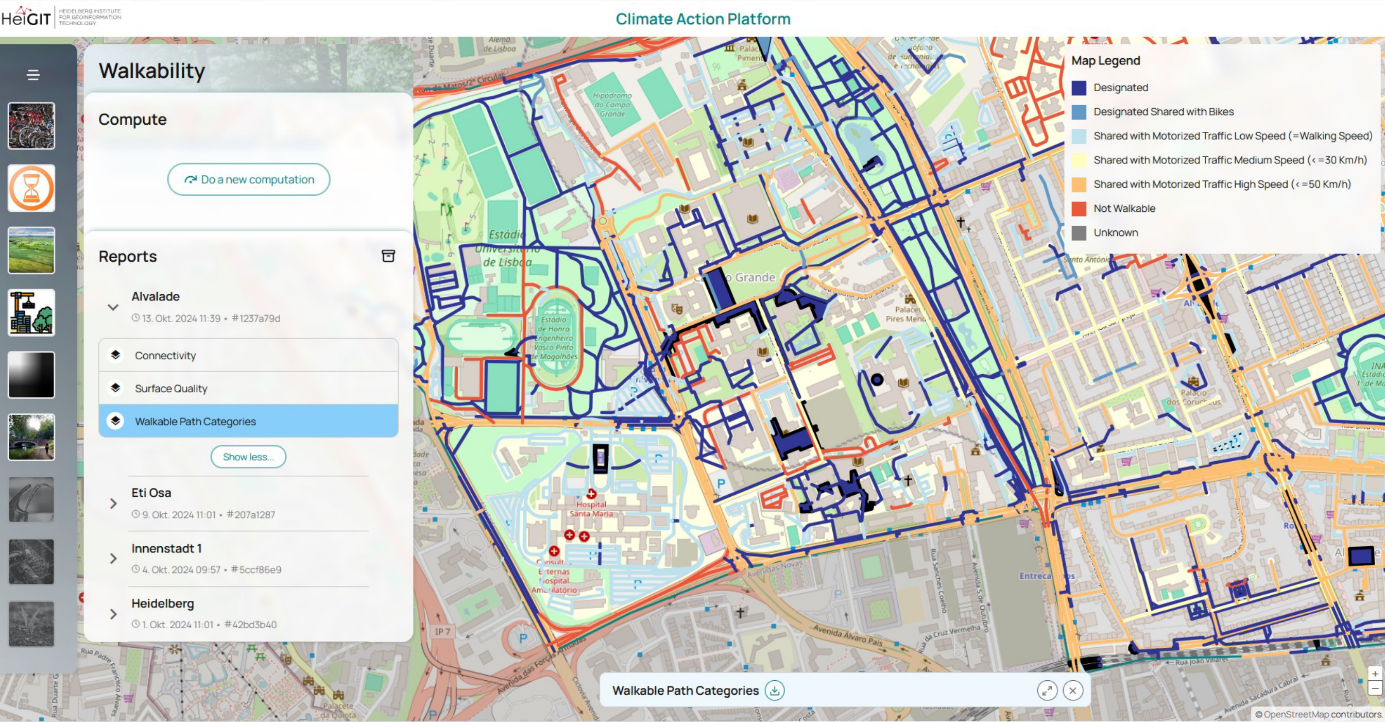

- Our first indicator, “Walkable Path Categories”, answers the question: “Who do I have to share this path with?”. It is a classification of all potentially walkable ways (OSM tag “highway=*”) and polygons (e.g., train platforms, squares, parking lots, etc.) according to whether they are designated for exclusive use by pedestrians (e.g., most sidewalks), or they are shared with bikes (e.g., paths tagged as “foot=designated & bicycle=designated & segregated=no”), or motorized traffic of different speeds (using OSM tag “maxspeed”). A street can still be relatively walkable even when shared with cars, as long as these have to drive very slowly and pedestrians have priority (e.g., “highway=living_street”). But as cars gain priority over pedestrians and drive faster, walking quickly becomes unsafe and less enjoyable.

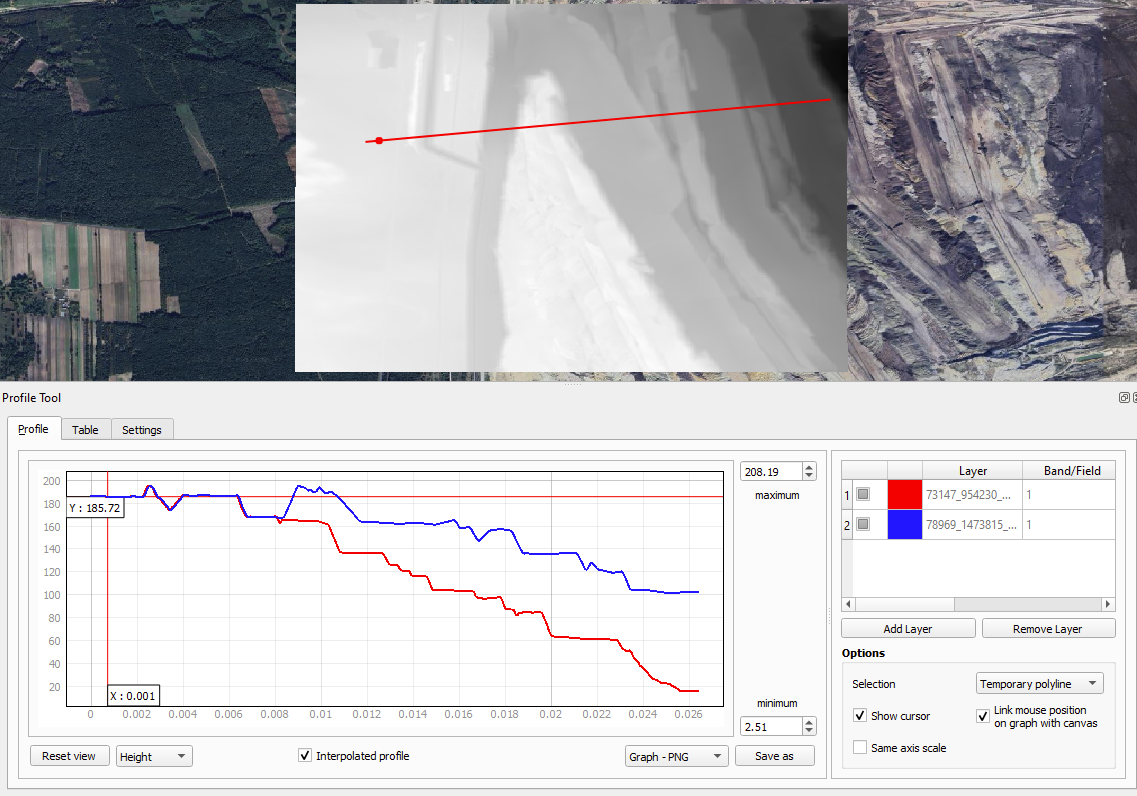

- A second indicator, “Surface Quality”, answers the question: “How comfortable is it to walk on this surface”, and describes how smooth the surface of walkable paths is. This is also an indicator of accessibility, especially important for people with limited mobility, or those who need to use wheelchair or wheeled walking frames. The indicator classifies paths into different surface quality levels using information of “smoothness” OSM tags. When these are not available, we also use the tags “surface” (e.g., asphalt, concrete, cobblestone, gravel) and “tracktype”.

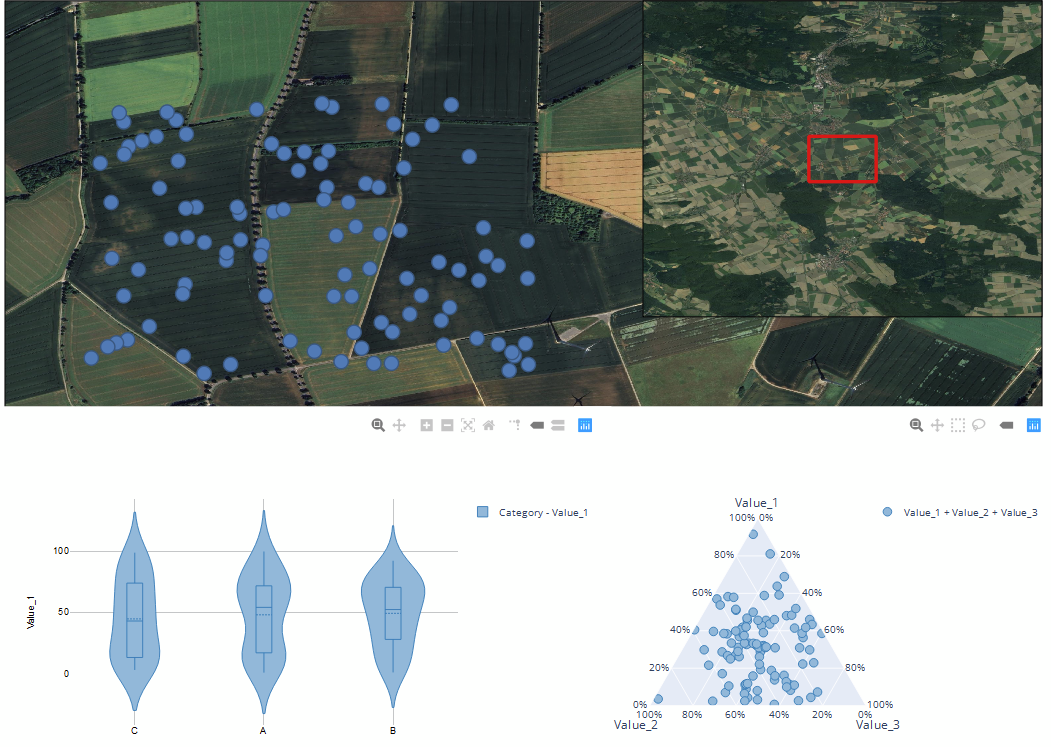

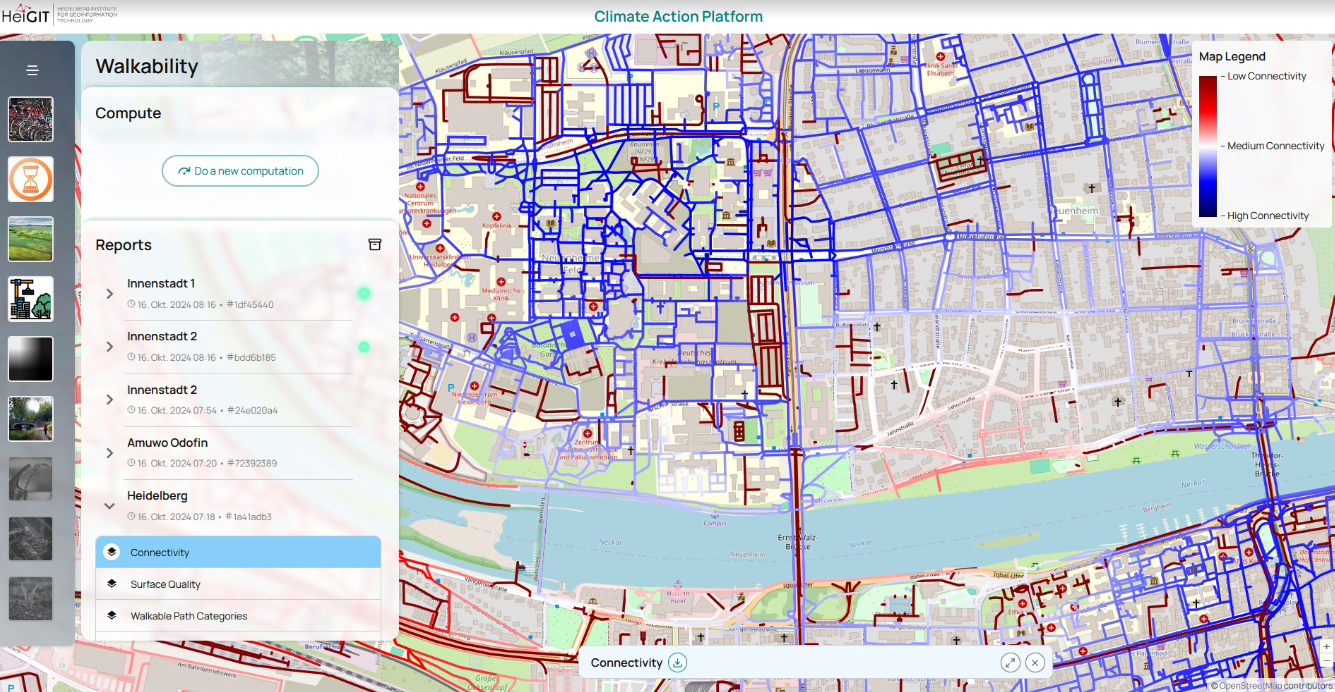

- Our third indicator, “Connectivity”, answers the question: “How directly do I get where I want to go?”, and captures how directly streets are connected to other locations in the surrounding area. Specifically, our indicator measures the fraction of nearby locations that can be reached within a short walk (e.g., 15 minutes) from a given street segment, relative to the number of locations that could be accessed “as the crow flies” (i.e., in a straight line). The better connected paths are in a street network, more locations are easily accessible by foot, which makes walking a more attractive transportation mode.

Future Developments

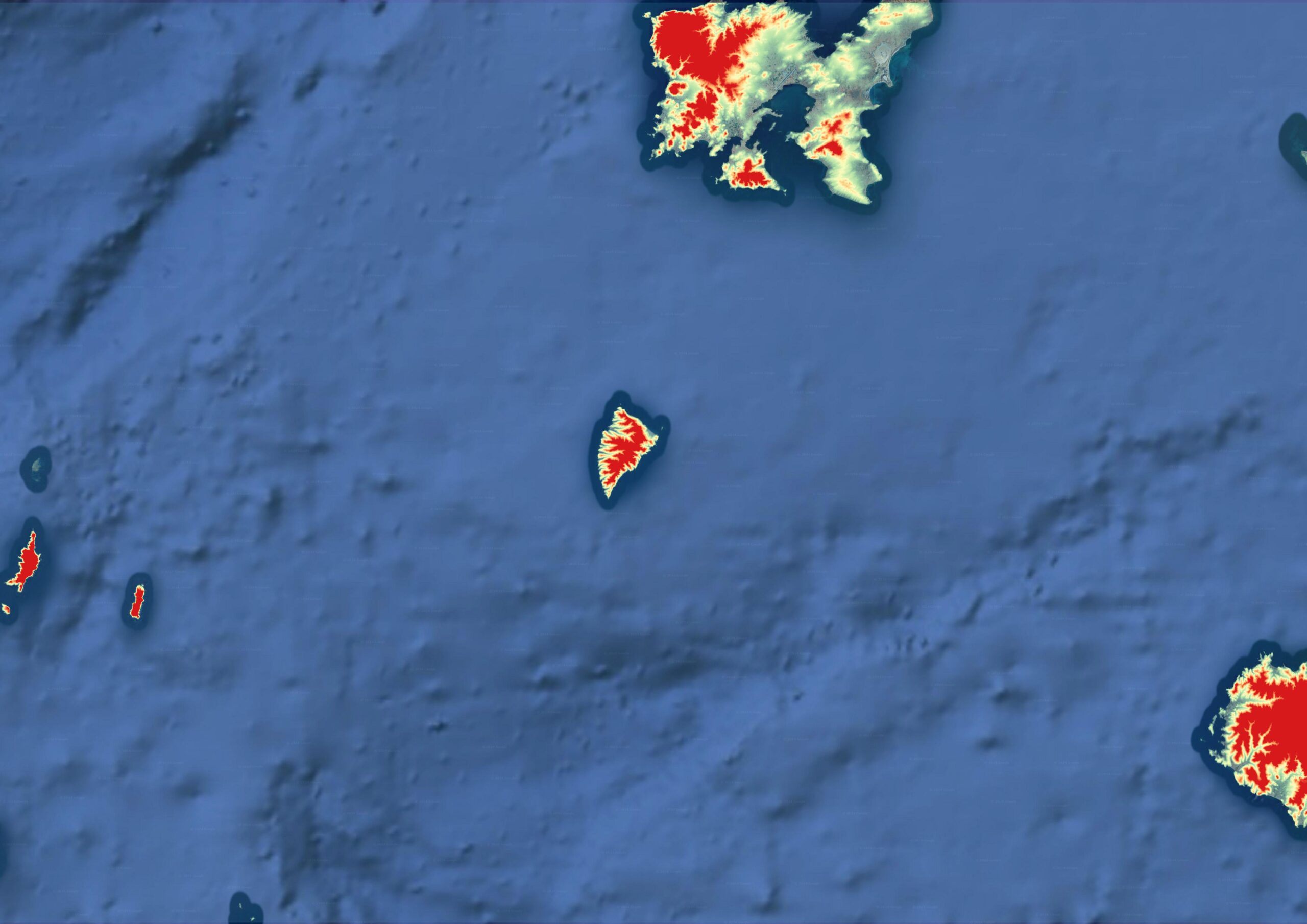

We continue to refine our current indicators and plan to develop new ones. For example, an upcoming indicator of “Greenness” will combine OSM-data with Sentinel-2 satellite imagery to calculate the average Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI, a proxy for vegetation density) of a small area surrounding each street. Greener streets, with more trees and surrounding parks and gardens, are more pleasant and attractive to walk through. We are also planning indicator to calculate the levels of noise and air pollution of different streets, which also impact how pleasant it is to walk through a given area.

So far, our indicators are limited by the quality and completeness of OSM data. To enhance the reliability and scalability of our walkability index, we plan to integrate remote sensing data and street-level imagery from the Mapillary platform. Remote sensing and street-view data offer complementary insights, helping confirm and correct OSM tags. Combining additional data with OSM tags will allow us to refine our classifications, ensuring that path types and traffic conditions are as accurate as possible.

Looking Ahead

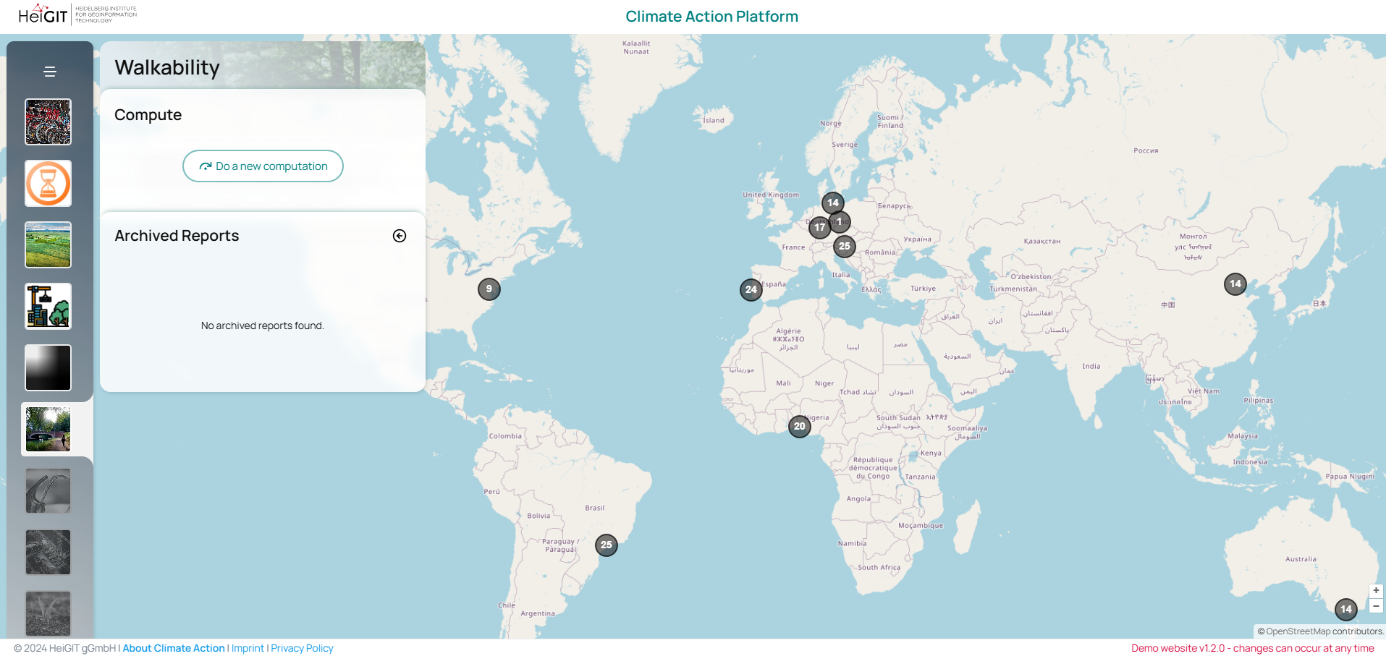

The walkability index is still under development, and future research will assess how well our adapted analysis of pedestrian friendliness aligns with the real-world experiences of different population groups. Ultimately, we plan to share this index via an online platform, providing cities with the tools they need to create more climate-conscious urban environments.

If you are interested in this work, want to collaborate, or help develop new tools, contact Kirsten at kirsten.vonelverfeldt@heigit.org.