When you think about viral content, maps are not the first thing that comes to mind. And yet, it is not uncommon to see maps of all shapes and sizes dominating social conversations about various issues – as well as non-issues.

In January 2020, the Australian bushfires were “the hottest” topic for every media. The artist Anthony Hearsey pulled publically-available satellite data about the fires from NASA and created a 3D rendering of all the fires that had been detected in a one-month period.

Courtesy: Anthony Hearsey

People mistook that compilation to be a recent satellite photo showing the live extent of the fire. Singer Rihanna put out a tweet of that visualization, and in no time, it had amassed 76,8000 retweets and comments. News organizations had to step in and clarify what that graphic actually represented.

But that’s just one example of a trending map. Virtually anything interesting could make up for the content of a viral map – if done correctly.

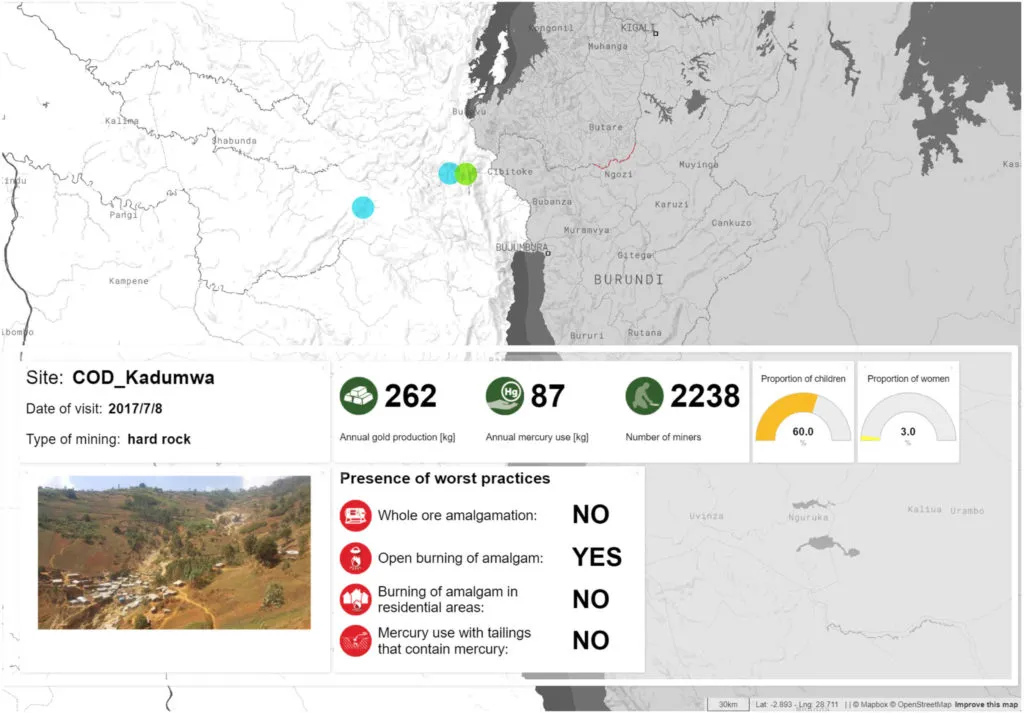

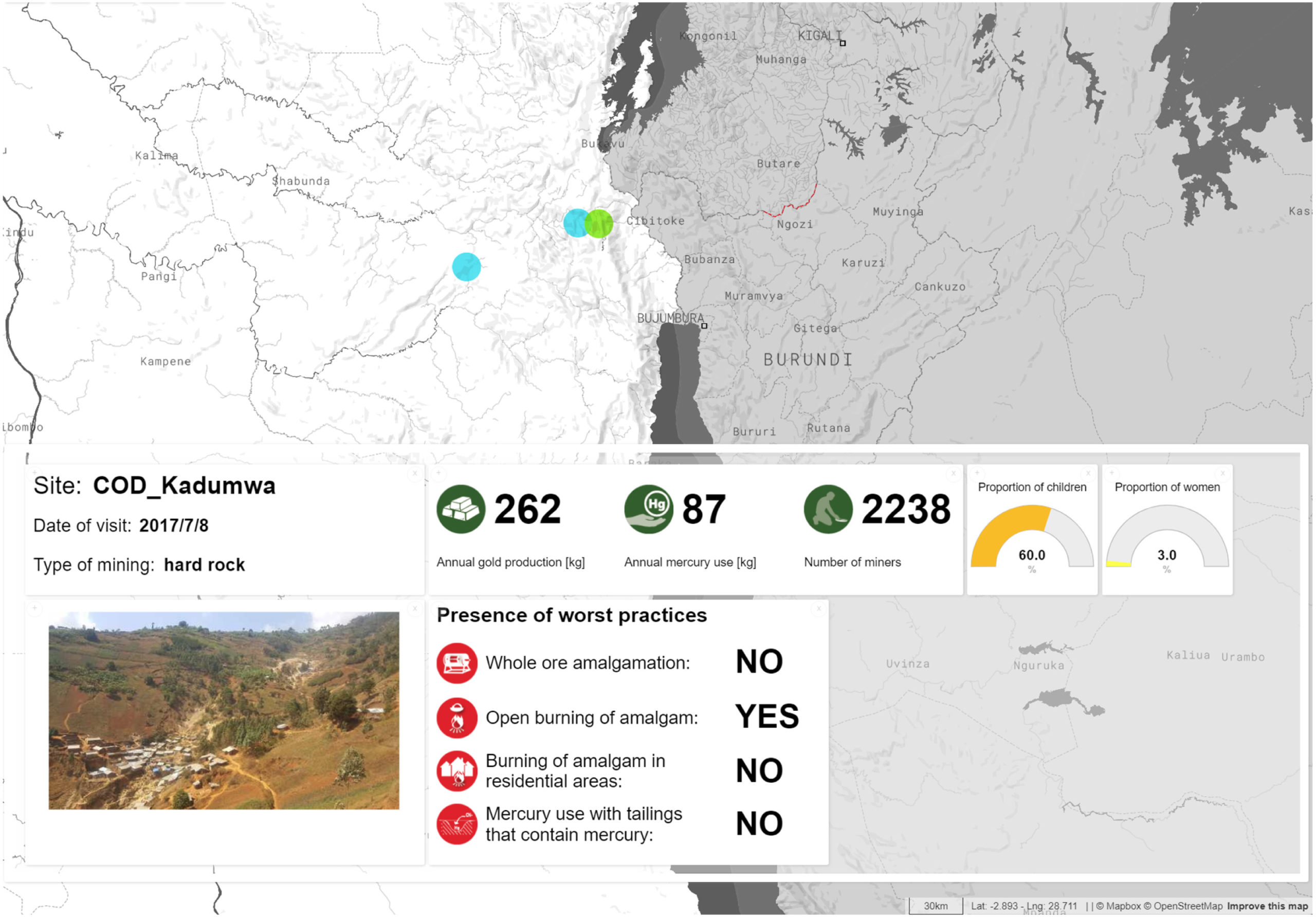

Like Nik Freeman’s map of the nearly 5 million Census Blocks in the United States where no one lives:

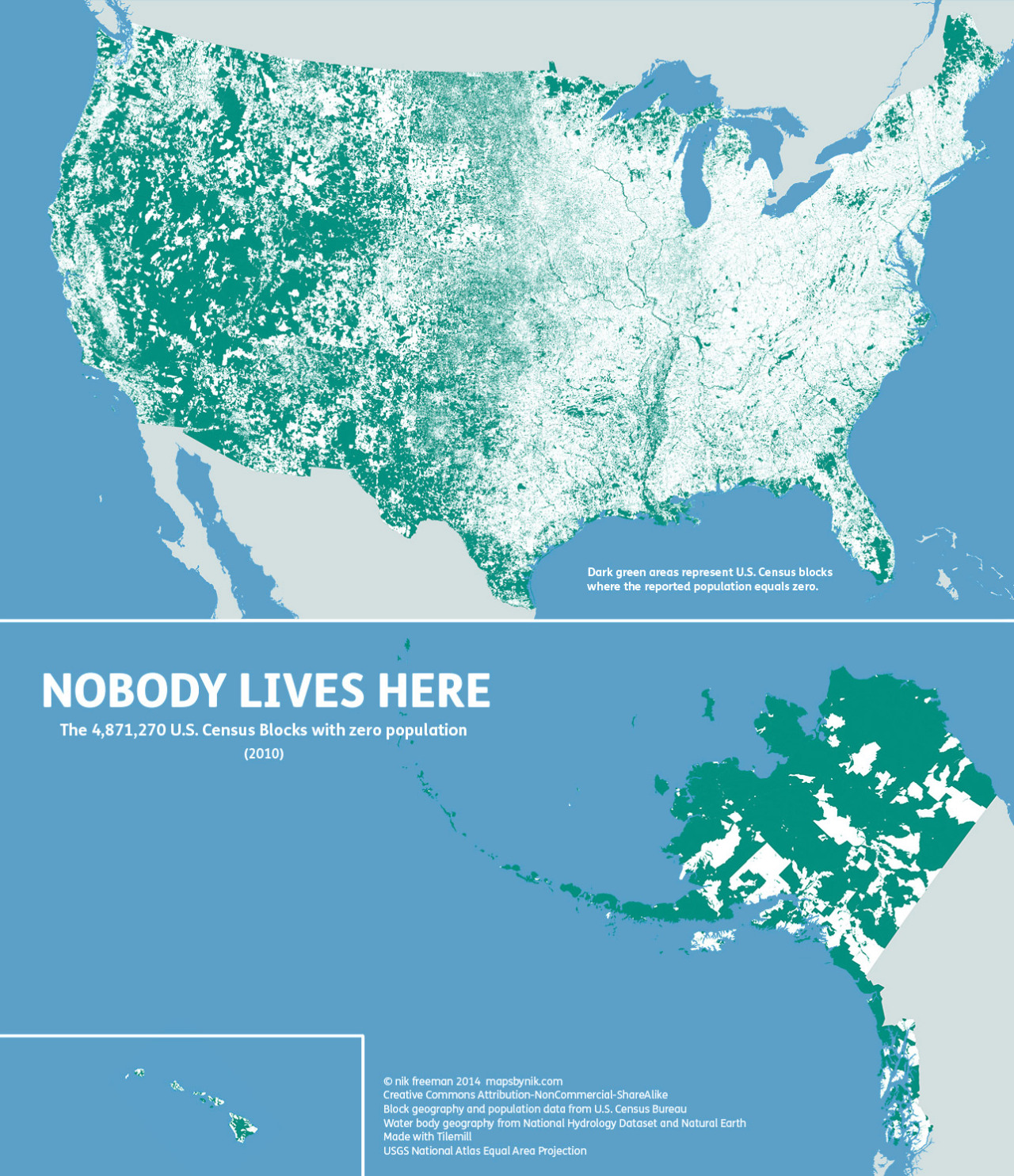

Or Rome2rio’s modern-day heatmap of the travel times from London to every airport around the world – which uses a map from 1914 as its base:

But what is it that makes a map click with its audience? Researchers and cartographers alike are trying to decode the mystery.

And while nobody has stumbled upon a fixed formula using which you would be able to craft viral maps intentionally, case study examples have shown that there are certain elements that can be associated with maps that are shared widely on social media or, depending on their content, via news organizations.

Elements of viral cartography

1. Simplicity

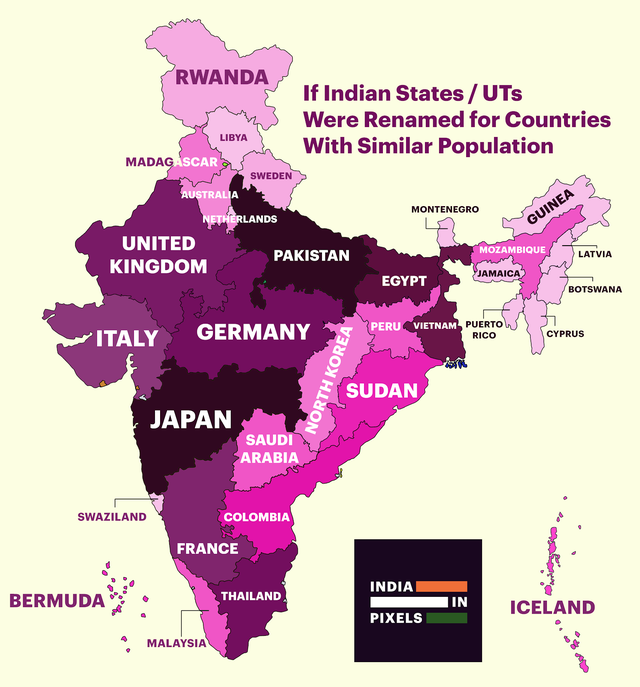

Like all good maps, viral maps are easy to understand. It shouldn’t take anyone more than a few second to get what the map is talking about – like the one below that shows you just how densely populated India is:

Courtesy: India in Pixels

2. Usefulness

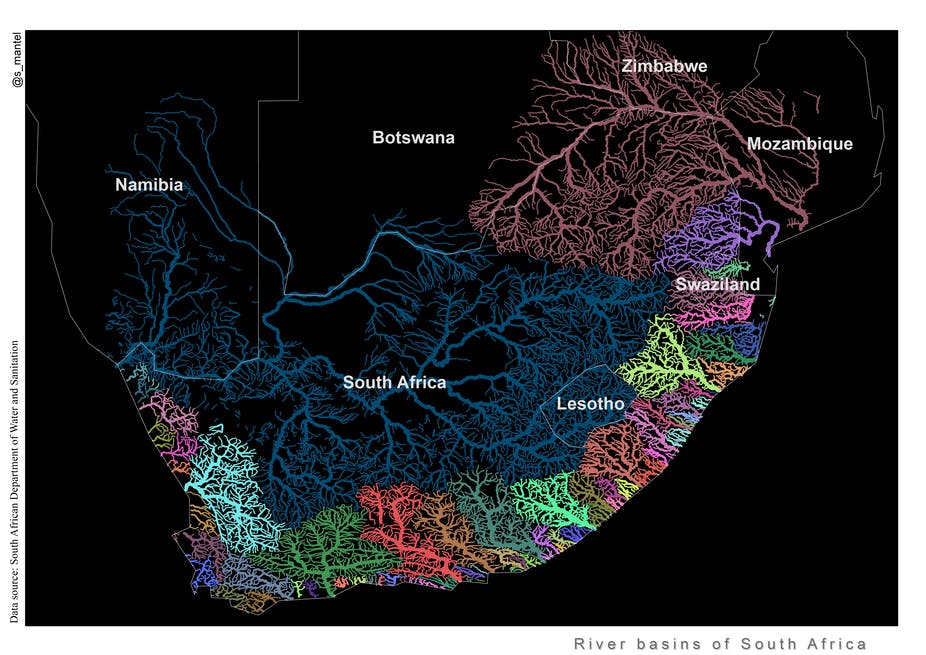

A map could also go viral if it answers a question of interest for a diverse group of people. When river ecologist Sukhmani Mantel decided to bathe the river basins of South Africa in the colorful palette below, she didn’t know it was going to go viral. But South Africans told her how they wished they had access to this map when they were in school. And you have to admit, maps like this would have made geography even more fun for all of us!

3. Aesthetics

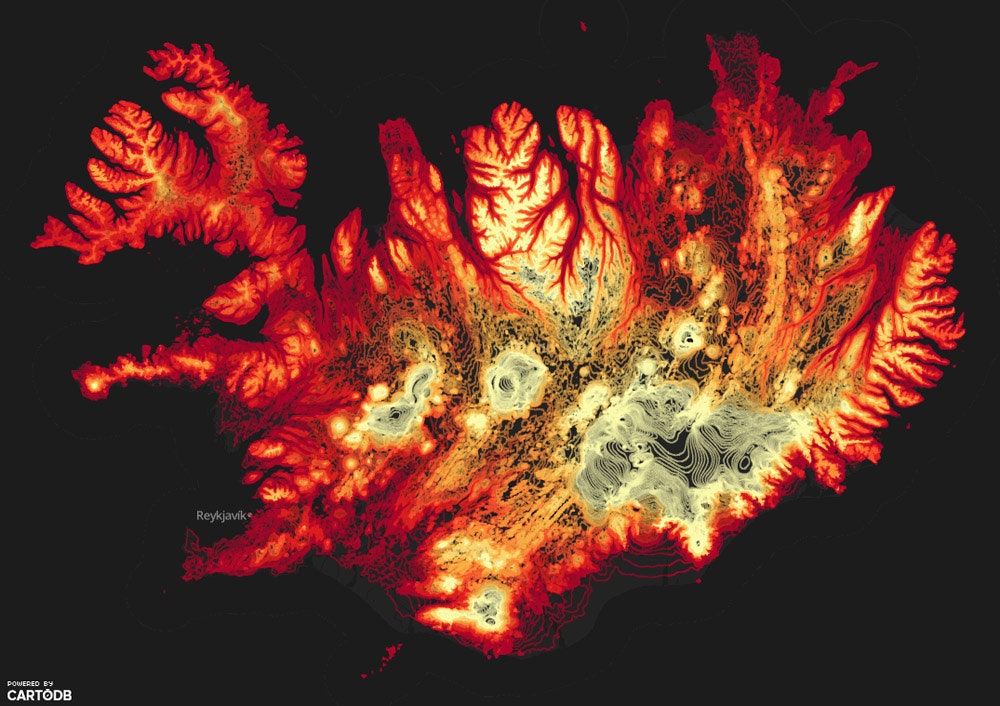

Aesthetics also plays a very important role in making a map appeal to the masses. Let’s take the topographic map of Iceland below as an example. When you think about Iceland, you think icy whites or cold blues – not the deep reds that show the lowest elevations or the bright yellows that show the highest!

Courtesy: Aitor Garcia Ray

4. Emotional resonance

It doesn’t matter if its awe, or surprise, or joy, or fear, or anger – if a map is able to elicit an emotional response from you, chances are, you would want to share it with your friends or colleagues. Like the map below that divides Russia according to which country is the nearest to any particular point within the country, as the crow flies.

Courtesy: galacticpasta

You only have to go to Reddit to see some of the responses to this map to understand the importance of emotional resonance. Like this Norwegian guy who just found out that there is only one country that separates Norway from North Korea!

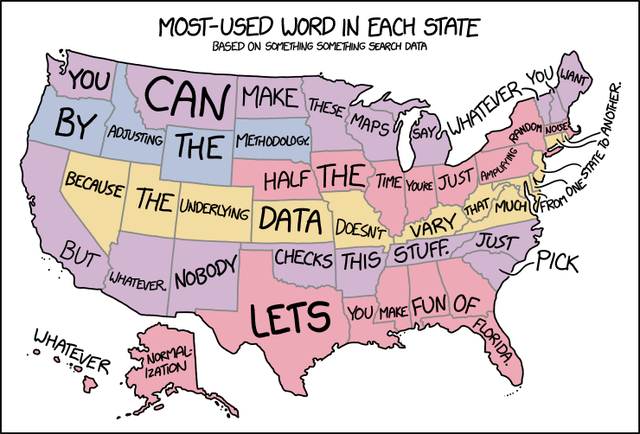

5. Humor

Courtesy: xkcd

The map above is a pointed critique that many maps that get shared on social media are just fluff rather than substance. But a little lightheartedness goes a long way to exorcise stress and connect us to each other – especially in these challenging times.

6. Topicality

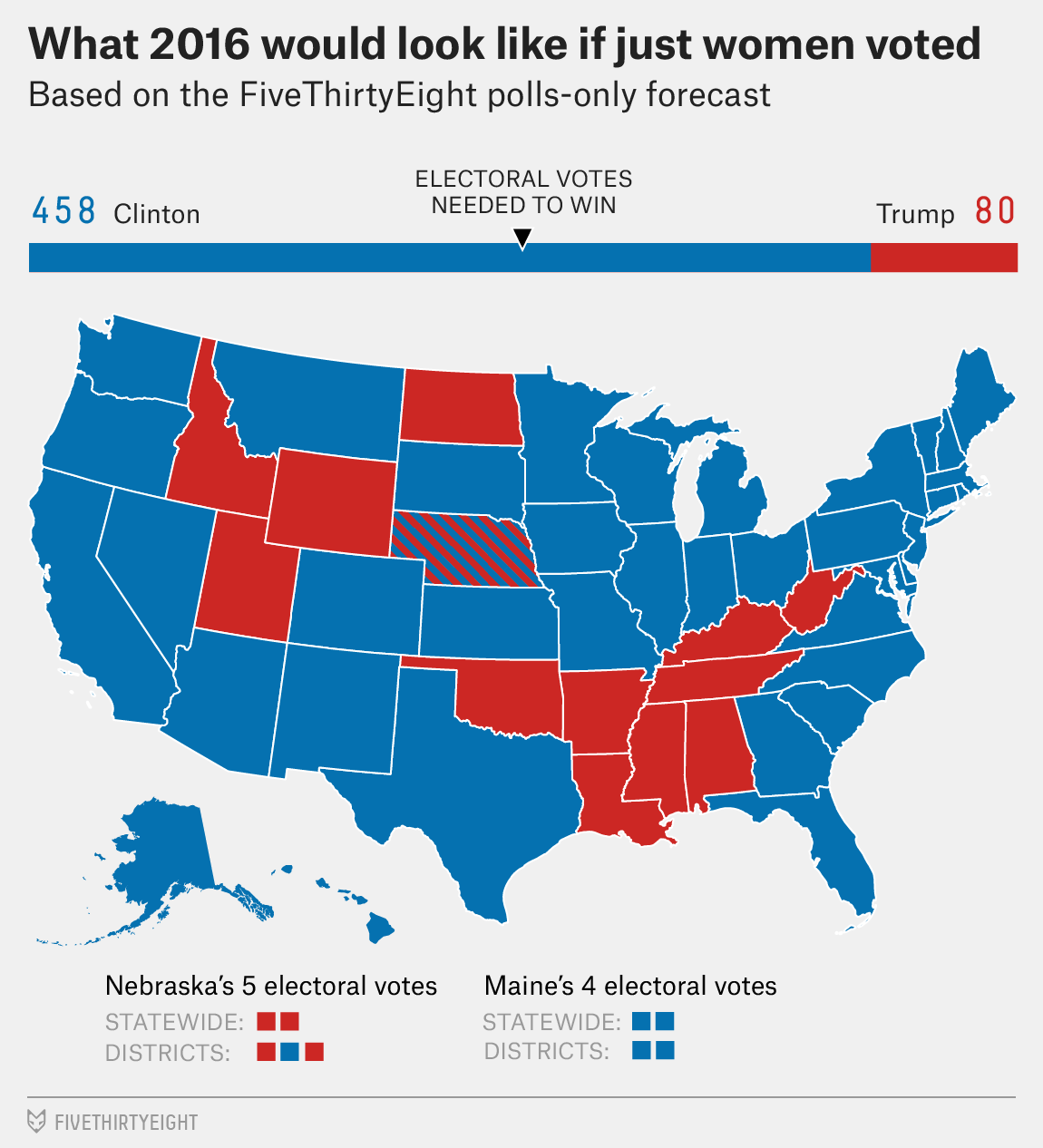

Timing, of course, can also play a crucial role in making a map viral. Nate Silver’s map below was released by statistical news website FiveThirtyEight just as the 2016 US presidential elections were heating up. It’s a projection map that gives you a view into a potential future – “if only women voted”. Not only has this map been viewed and shared millions of times on social media, but it also checks the box for the argument that imitation is the sincerest form of flattery.

Viral maps and fake news

While researching viral cartography, Penn State geographer Anthony Robinson found that the above map had spawned a series of copycat maps, many of which also went viral. These included both the serious (what “if only people of color voted”) and the silly (“if only goats voted”).

Robinson found more than 500 such unique maps on the internet. And in the context of our battle with fake news, this is a very dangerous thing. When a map conveys more validity than it deserves, it becomes very easy to fabricate the truth; we all know how convincing auto-generated videos called “deep fakes” seem.

As Robinson says, “It’s cool that anybody can make a map now. They can take election data and do something creative with it, and it can be very helpful. But it’s also easy to make something that looks like it’s authoritative and use it as a weapon.”

The copycat maps

We must move beyond the notion that maps only show what’s “already there”. Maps can help to “create” perceptions and shape people’s “future actions” as well.

This is why it is more important now than ever to understand where a map has originated. In an ideal world, people would question map accuracy or introspect the intentions behind the map. In our world, technology will hopefully make up for the lack of skepticism among people soon. Machine learning image detection algorithms, like those from Google Cloud Vision, can be used to trace the provenance of viral maps and see how they spread online.

But until that happens, it’s our job to ensure that we and those around us, map responsibly and not just create anything for the sake of virality.

Watch this as a video story: