This research shows what is understanding of the term “map” and how it evolved over time

With the rise of digital technologies, mobile apps, autonomous driving, IoT, and other technologies, the word “map” has significantly evolved. It seems that its meaning has evolved with time, and it is now understood differently between generations, cultures, and geographies. No doubt, the development of location-based technologies has led to a growing need for the systematization of basic concepts, including defining what a map is. Last year we’ve supported reachers trying to gather the data about differences in understanding of the term “map” and now the research is finally out.

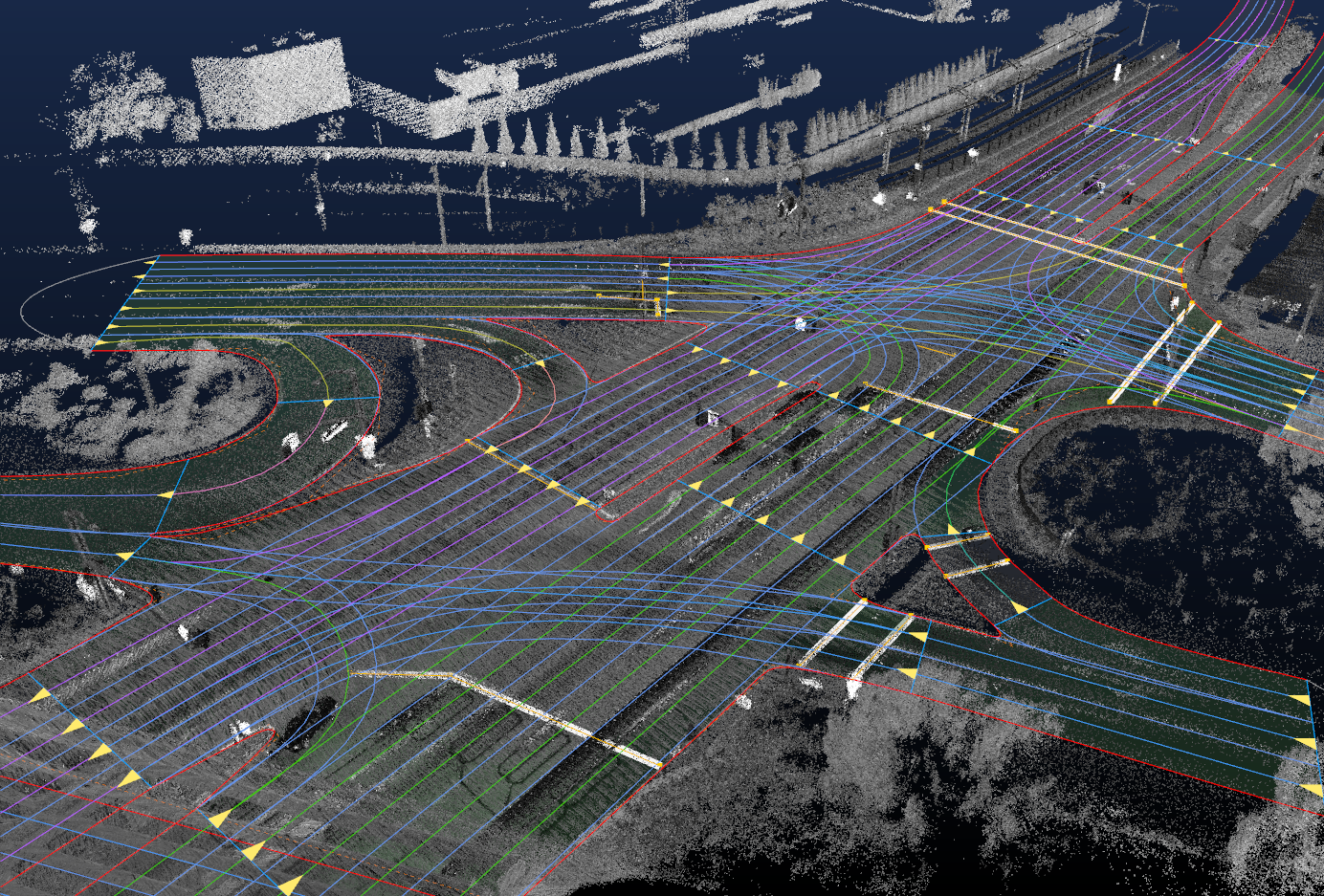

The research conducted by Dariusz Gotlib and Robert Olszewski (Faculty of Geodesy and Cartography, Warsaw University of Technology), and Georg Gartner (Department of Geodesy and Geoinformation/Research Division Cartography, Vienna University of Technology), explored how modern geoinformation technologies, affect the understanding of what a map is. The research reveals the role of the map in indirect cognition and learning of geographical space. This research on a group of nearly 900 respondents from various countries shows that a social understanding of mapping concepts is evolving and covers the entire spectrum of geoinformation products. Without a doubt, the latest geoinformation solutions, for instance, navigation applications and, specifically, applications supporting autonomous vehicles’ movement, have had a particular impact on the map concept.

Of course, you must have come across several instances in which the words “map” and “mapping” have been used, for example, mathematics, logic, biology, cartography, robotics, and computer technology. You will find all these terms in cartography virtually because it is a discipline that deals with the art, science, and technology of making and using maps. According to International Cartographic Association (ICA), a map is “a symbolized representation of geographical reality representing selected features or characteristics, resulting from the creative effort of its author’s execution of choices, and is designed for use when a spatial relationship is of primary relevance.” However, there is no one fit all definition for maps. For instance, a commonly used description is; “a map: graphic representation, drawn to scale and usually on a flat surface, of features—for example, geographical, geological, or geopolitical—of an area of the Earth or any other celestial body.”

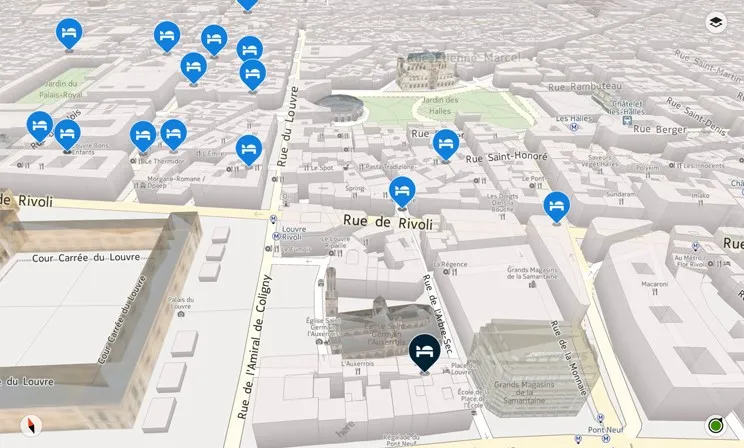

According to the research, more than 75% of the interviewees believed that they could use a car navigation system without looking at the screen. In contrast, two-thirds thought that the visually impaired could use a map. Most of the respondents, more than 80% actually, claimed that autonomous cars need a map to drive correctly. In comparison, another vast majority-more than 90%, concluded that a map could be three-dimensional as well as virtual.

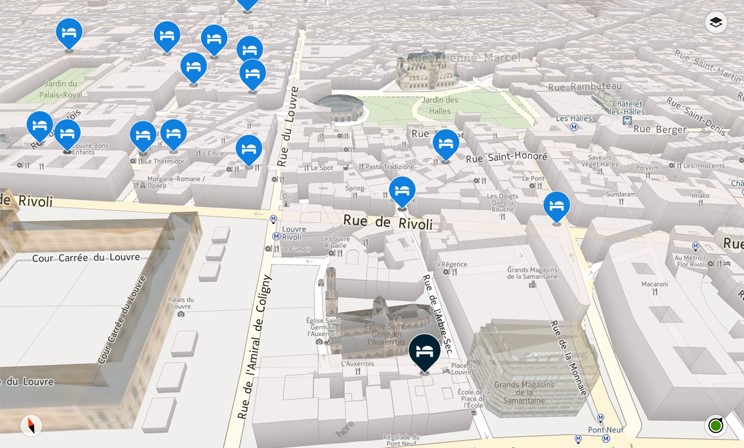

The survey also revealed some exciting responses when the interviewers were asked what they were willing to consider a map. Most respondents strongly believed that LBS applications are maps or use maps. In the car navigation application assessment, 40% of the respondents thought a car navigation application is a map. Interestingly, 80% agree with this assertion in the case of the Google Maps portal. Interestingly, as for many use cases, Google Maps is, in fact, a car navigation map.

Noteworthy, the survey results show consistency across respondents using different languages. In other words, the vast majority of the responses to questions raised in the questionnaire were consistent despite the different languages used, except for subjectivity or objectivity of the cartographic information message. 62% of the English-speakers thought the map is a cartographer’s subjective way of seeing reality, while 14% thought otherwise. 49% against 34% of German-speakers held similar views, while 57% of Chinese people believed the map is an objective reflection of reality and only 30% said the opposite.

This research definitely represented different cultures, places of residence, and different languages, and it is worth noting that the respondents had a comprehensive understanding of maps. In other words, there was no significant relationship between the responses and the gender, age, country of origin, and cultural backgrounds of the research participants.

Interestingly, many people believe that the graphic form of a map is not crucial in calling the product a map. The good news is that most of them are aware that the map user is no longer necessarily a human being. And that the cultural difference or language does not affect one’s understanding of the map concept. In fact, many people, as shown in the survey, considers maps to be models of geographical space that facilitate navigation. It has also come out clearly that many think maps to be carriers of information, not graphic images. This broad understanding of the map’s role today is precious in an era of widespread use of navigation and LBS applications.

Without a doubt, the general public’s perception of the map concept is extensive and far different from the “flat graphic representation at a specific scale.” In other words, the public seems to agree that maps are not solely associated with visualization. That is, visualization is not a prerequisite for the existence of maps. Instead, the map is a geographical reality model that can be communicated to the user in many ways by utilizing many senses. It is also important to note that the vast majority of the public admits (indirectly) that the user of the cartographic modelling process is not necessarily a human; it may be a machine, such as an autonomous vehicle.

In conclusion, we can say that digital technology development has significantly influenced the public perception of cartography’s role and the meaning of the map. It is apparent that the map concept is understood much more broadly now than even a decade ago. It is critical to note that regardless of age, gender, or language, people recognize the association between modern geoinformation products and the map understood as a reality model. Therefore, we can easily say modern cartography’s role is to adapt geoinformation products to the needs of a wide range of consumers of contemporary maps, including those who do not use graphic images as a source of information about surrounding space.

As noted by the authors of the research, when understood as an organized spatial dataset, a map becomes an essential element of interpersonal communication and the decision-making processes performed by robots, as exemplified by M2M (machine to machine) communication. The authors of the research determined that “a map means arranging data and giving them a proper structure in a way that is appropriate for cartography, according to a particular data model, to ensure optimal spatial information communication.”

Detailed research results and authors’ views on this subject can be found in the article available here.