Subtitle: Using Google DeepMind’s AlphaEarth on avocado site selection

A few years ago, I worked on a project evaluating potential sites for Hass avocados in Colombia. The process involved benchmarking existing farms, consulting agronomists, traveling across the country, and assembling climate and elevation data. It was fragmented, and the hands-on kind of work that’s hard to scale.

So when Google DeepMind released a model called AlphaEarth, I was curious. It encodes the entire planet as searchable environmental fingerprints. And it got me thinking about a simple question:

What if you could point at the coordinates of successful farms and ask, “Where else on Earth looks like this?”

That’s similarity search applied to agriculture. What makes it practical now is that satellite observations are encoded as embeddings – compressed representations that capture environmental patterns – rather than raw data across dozens of variables.

How It Works

AlphaEarth captures a full year of satellite observations into a 64-number fingerprint for every 10×10 square meters on Earth. The model was trained on optical imagery, thermal data, and radar, but also learned to predict climate variables, elevation, and vegetation structure. So the fingerprint also encodes seasonal patterns, temperature regimes, and terrain, among others.

Two locations with similar fingerprints have similar environmental conditions. If you know where something works, you can find other places with matching conditions. This means taking some productive farms and searching globally for environmental analogs.

What I Tested

I chose Hass avocados partly because of my Colombia experience, partly because there’s no global suitability map for the crop. The FAO has frameworks for staples (maize, wheat, rice) but not for specialty crops. Some avocado maps exist, but don’t distinguish varieties. Academic studies exist at the country level, but nothing global.

I identified 24 productive Hass farms across Mexico, Colombia, South Africa, Kenya, California, Spain, Peru, Chile, and a few other regions. I extracted their AlphaEarth fingerprints and computed similarity scores for every land square on Earth.

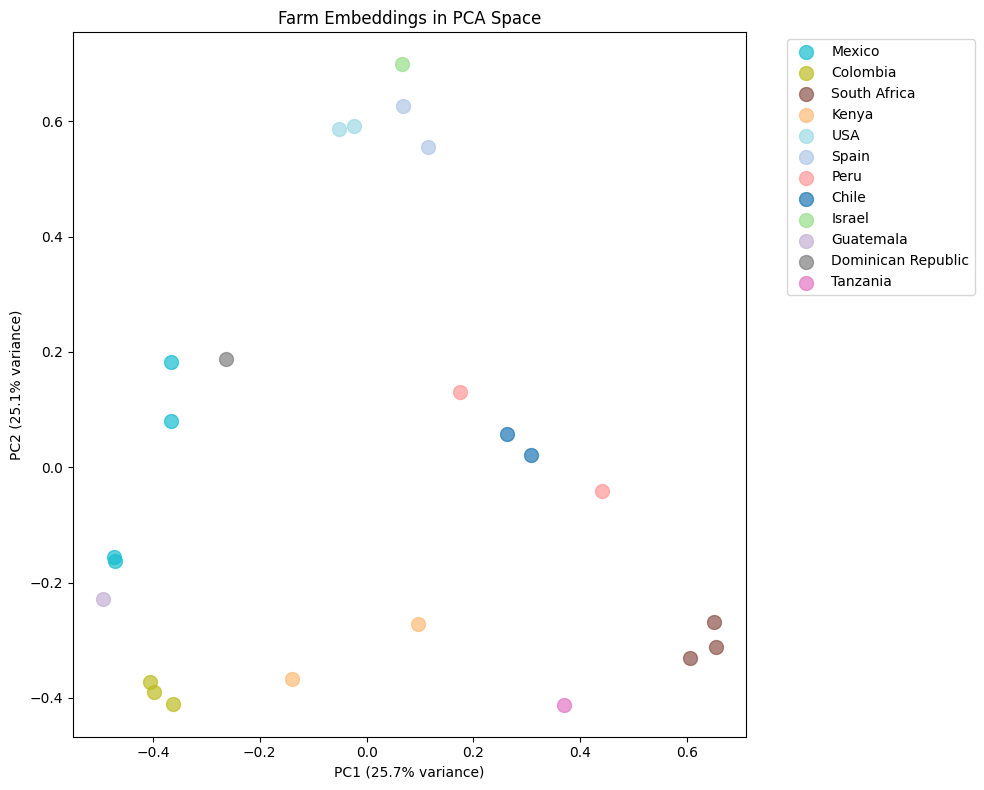

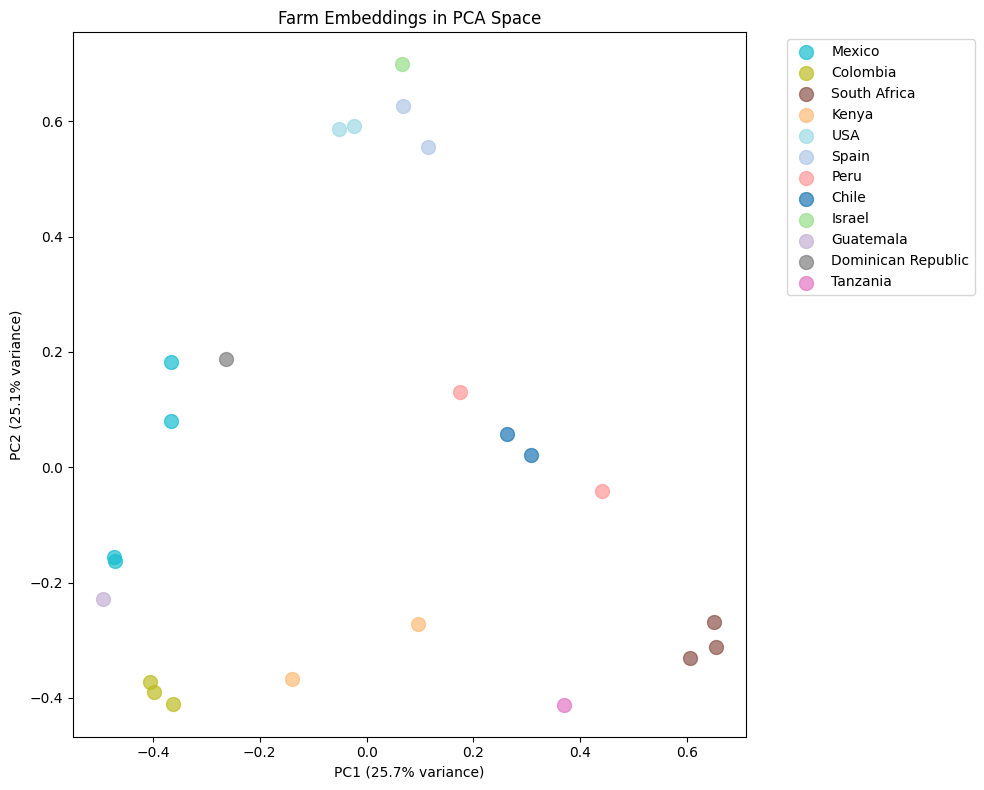

Figure 1: PCA projection of farm embeddings. Farms cluster by environmental similarity, not geography – Peru and South Africa sit close together despite being 10,000 km apart

The map highlighted known production regions, which was reassuring. More interesting were the cross-continental matches: Spain and California overlapped despite being 9,000 km apart. Peru matched South Africa. The model identified environmental analogs across distant regions, which serves as a powerful hypothesis generator for site selection.

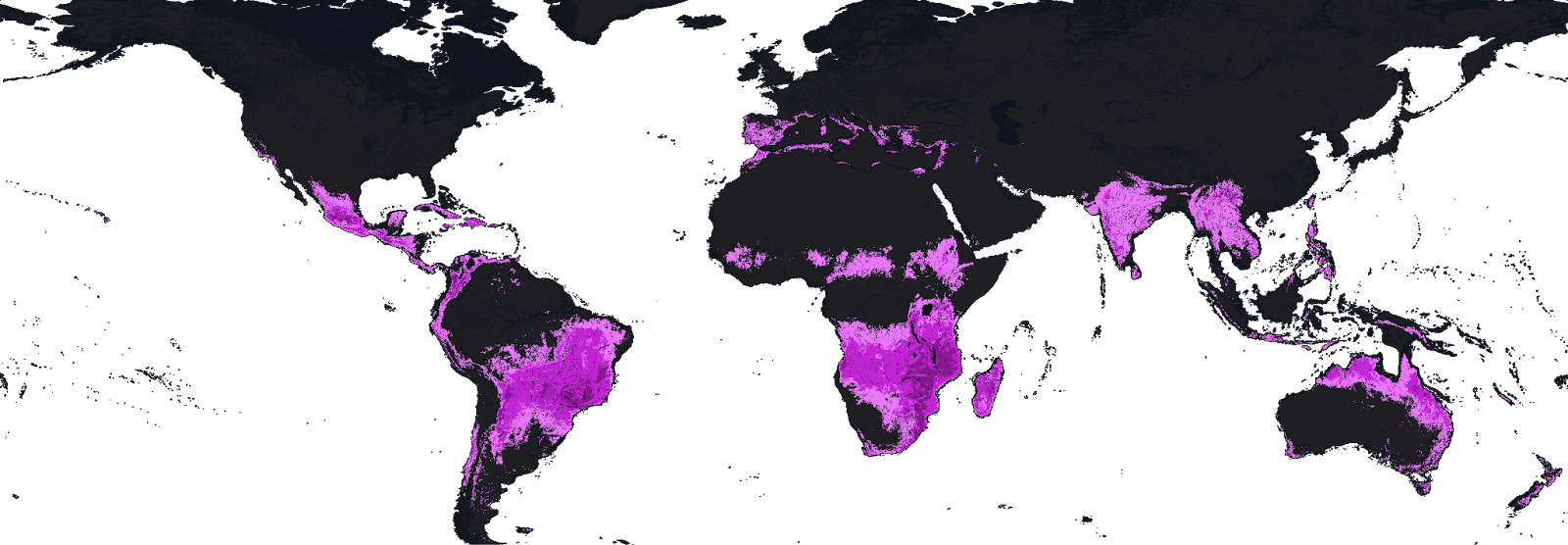

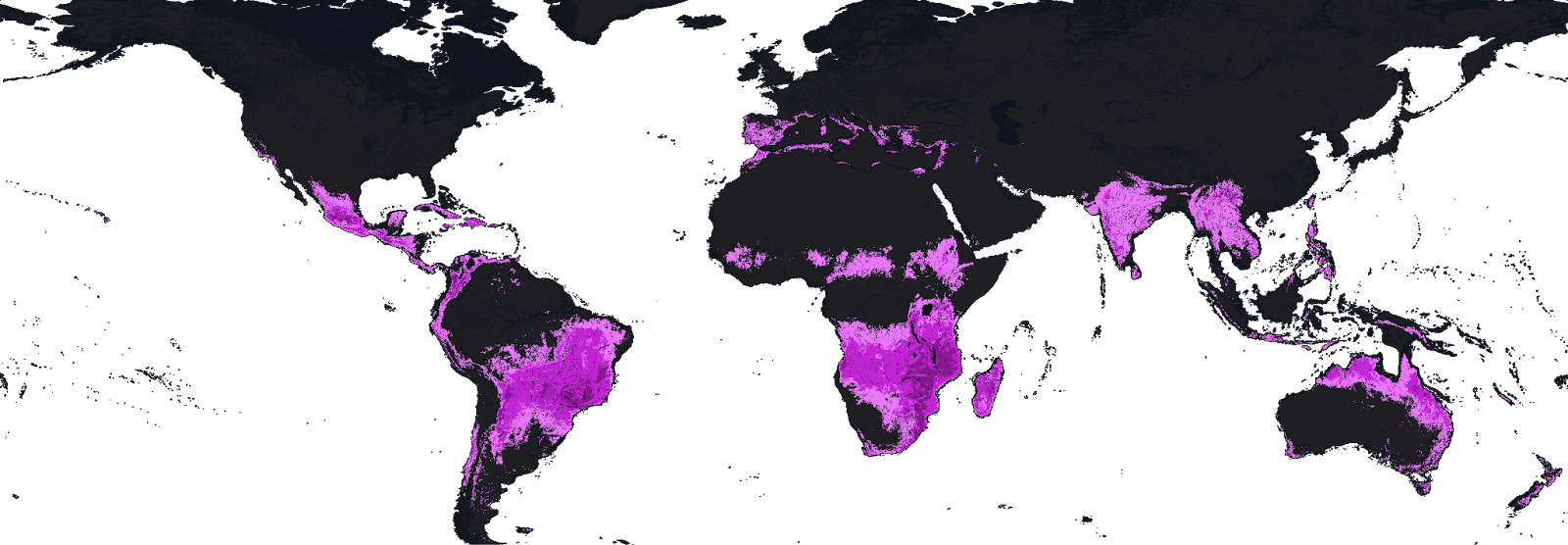

Figure 2: Global similarity map. Global similarity to 24 reference Hass avocado farms. Brighter = higher biophysical similarity. Image by author.

After filtering out established exporters, ten high-scoring potential new regions stood out:

| Country |

Region |

Likely Match |

| 🇦🇷 Argentina |

Salta Province |

Chilean farms |

| 🇿🇼 Zimbabwe |

Manicaland |

South African farms |

| 🇲🇼 Malawi |

Southern Region |

South African farms |

| 🇦🇺 Australia |

Queensland |

Kenyan farms |

| 🇧🇷 Brazil |

São Paulo highlands |

Colombian farms |

| 🇨🇷 Costa Rica |

Central Valley |

Colombian farms |

| 🇷🇼 Rwanda |

Western Province |

Kenyan farms |

| 🇬🇷 Greece |

Crete |

Spanish farms |

| 🇮🇹 Italy |

Calabria |

Spanish farms |

| 🇨🇳 China |

Yunnan |

Kenyan farms |

Whether these could actually support commercial production depends on many factors the satellite can’t see. But as starting points for investigation, they’re interesting.

What It Can’t Do

Similarity search finds places that look environmentally similar to reference sites. It doesn’t account for water rights, soil chemistry, access to markets, infrastructure, regulations, or pest pressure. A location can match perfectly with biophysical signals and still be unviable.

The approach also inherits whatever biases exist in the reference set. If your 24 farms skew toward irrigated lowland production, the model will find more irrigated lowlands. Diversity in the training data matters.

So this isn’t a replacement for agronomic expertise or on-the-ground assessment. It’s a screening tool, a way to narrow the search space before doing the expensive work.

Where It Gets Interesting

The Hass avocado exercise was a test case. The broader question is what similarity search could enable for agriculture.

Niche crops without suitability maps. Similarity search provides a fast way to screen potential regions for specialty crops like macadamia, saffron, truffles, or dragon fruit. If you have 20-30 reference farms, you can query the entire planet.

Climate adaptation monitoring. Run the same analysis year over year and track how suitability zones shift. Where is it becoming more similar to productive regions? Where is it becoming less? The dataset provides a consistent baseline.

Analog-based knowledge transfer. If a region matches Colombian highland farms, Colombian growing practices-variety selection, irrigation schedules, pest management-are a reasonable starting point for trials. The “likely match” column could be a hint about where to look for relevant expertise.

Investment screening. Before committing to detailed due diligence on a region, a similarity check could serve as a filter and flag whether the biophysics even make sense.

The Bigger Picture

Google made AlphaEarth openly available through Earth Engine. Using it requires some basic programming, but the data barrier is gone. That’s a shift from a world where global environmental analysis required significant resources.

What gets built on top of it is an open question. The avocado map I made is one example. Someone else might use it for reforestation site selection, or renewable energy siting, or tracking ecosystem change. The same infrastructure applies.

For agriculture specifically, similarity search won’t replace the hard work of agronomy, soil science, and market analysis. But it might change where that work starts. Instead of selecting regions based on intuition or proximity, you could select based on environmental analogs and then do the real diligence.

That’s a small shift in process, but it could open up options that wouldn’t otherwise get considered.

Would you like to share your story? Contact us: info@geoawesome.com