Building on the themes of our previous coverage in Tech for Earth, the past month has seen a convergence of space technology, artificial intelligence, and cartographic innovation. Currently, the field is producing real-time, decision-ready intelligence designed to address climate resilience, infrastructure safety, and environmental protection. This evolution is creating what can be described as a “living digital nervous system,” where multiple technologies – once considered separately – are now intersecting through real-world and spatial information.

Orbital Vision: The Completion of the Sentinel-1 Family

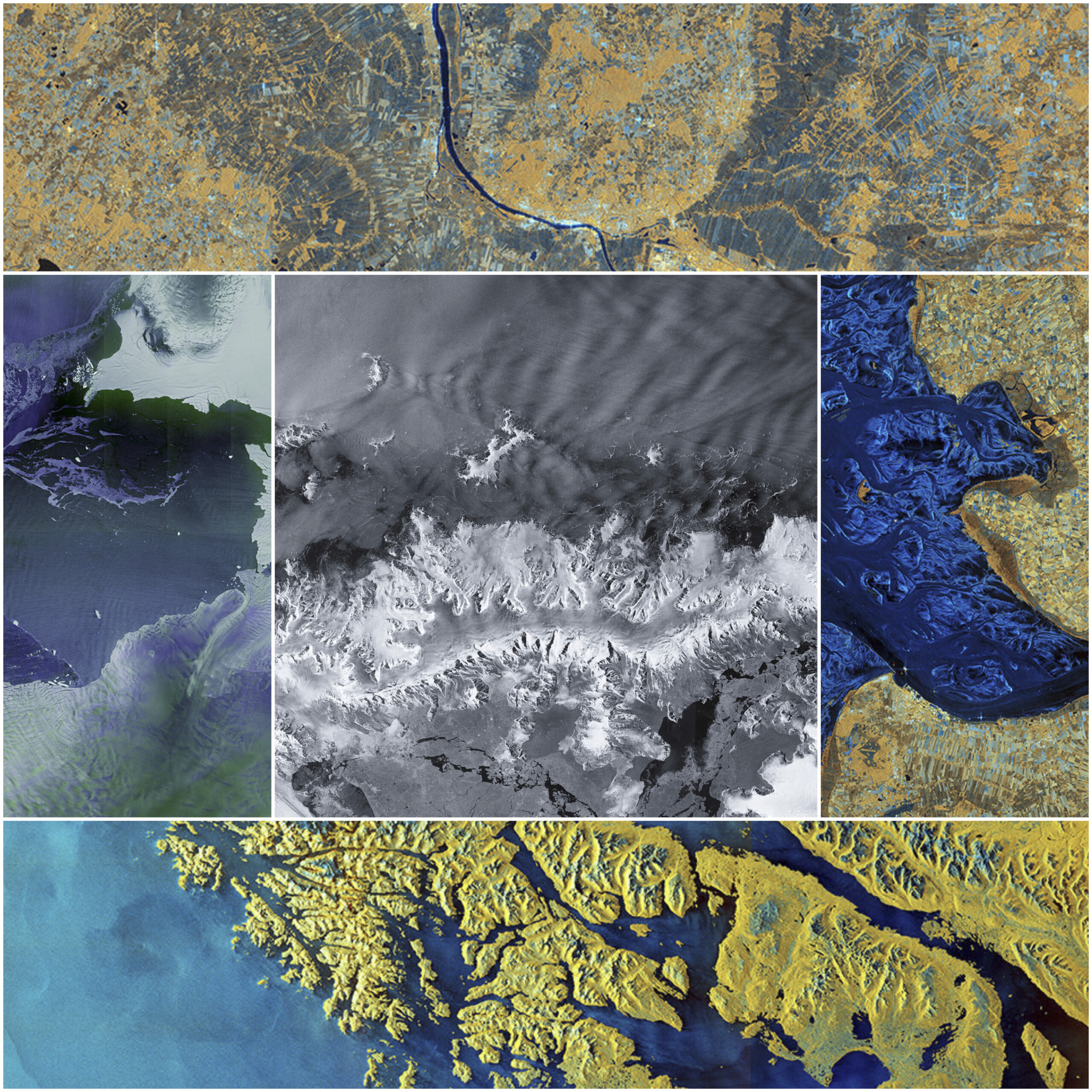

A major milestone for the European Space Programme occurred on November 4, 2025, with the successful launch of the Copernicus Sentinel-1D satellite aboard an Ariane 6 rocket. This satellite completes the first generation of the Sentinel-1 constellation, ensuring radar data continuity for the next decade. Remarkably, Sentinel-1D delivered its first high-resolution radar images within just 50 hours of launch, a feat believed to be a new record for space-based radar. These “first light” images captured the fragile beauty of the Antarctic Peninsula and the Thwaites Glacier, as well as the southern tip of South America and the city of Bremen, Germany.

The Sentinel-1 mission provides a “radar vision” that can penetrate thick cloud cover, fog, and rain, acquiring images day or night. This capability is essential for tracking subtle changes in tropical forests, monitoring volcanic activity, and quantifying ground deformation after earthquakes. In tandem with this radar expansion, the EU Space Programme is also preparing for the launch of Copernicus Sentinel-6B, which will continue a thirty-year legacy of centimeter-precision sea-level monitoring. This mission is dedicated to coastal cities like Rotterdam and Venice that face increasing flood risks as global sea levels rise at record rates.

AI-Powered Environmental Intelligence

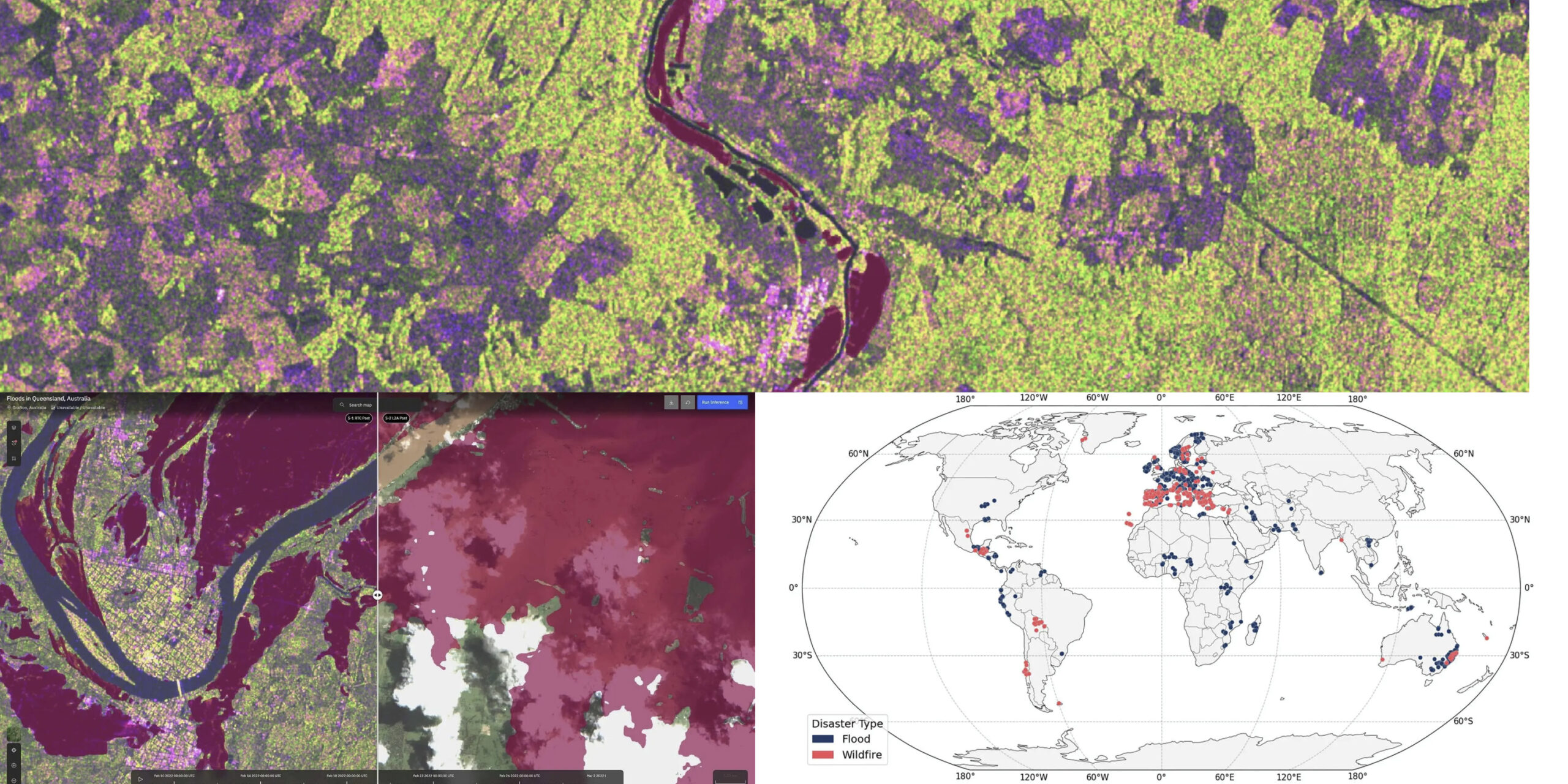

The integration of generative AI and geospatial data has reached new heights with several major releases. IBM and the European Space Agency (ESA) have open-sourced ImpactMesh, the first global multi-modal dataset for analyzing extreme floods and wildfires. By fusing radar, optical, and elevation data from the last decade, their fine-tuned TerraMind model can now produce burn scar maps with 5% higher accuracy than traditional methods. These models are designed to improve disaster preparedness by allowing responders to see through storm clouds or smoky fires that typically block optical sensors.

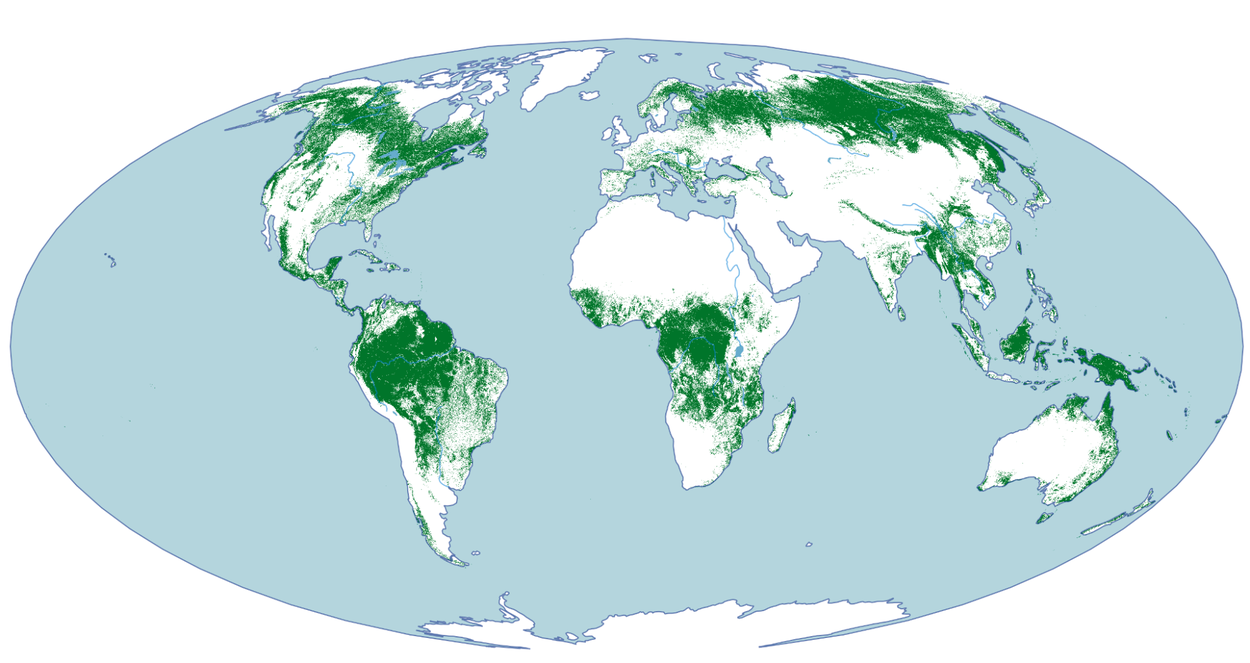

In the realm of meteorology, Google DeepMind introduced WeatherNext 2, an AI forecasting model capable of generating hundreds of possible weather scenarios in under a minute. It is 8x faster than previous versions and provides hourly resolution, surpassing previous state-of-the-art models on 99.9% of variables such as temperature, wind, and humidity. Furthermore, in a move for biodiversity, Google Research and DeepMind released a 10-meter resolution map that distinguishes natural forests from commercial plantations. This dataset is useful for compliance with the EU Regulation on Deforestation-free Products (EUDR), ensuring that products like coffee and cocoa sold in the EU do not contribute to the degradation of biodiversity-rich ecosystems.

The Advent of Autonomous and Agentic GIS

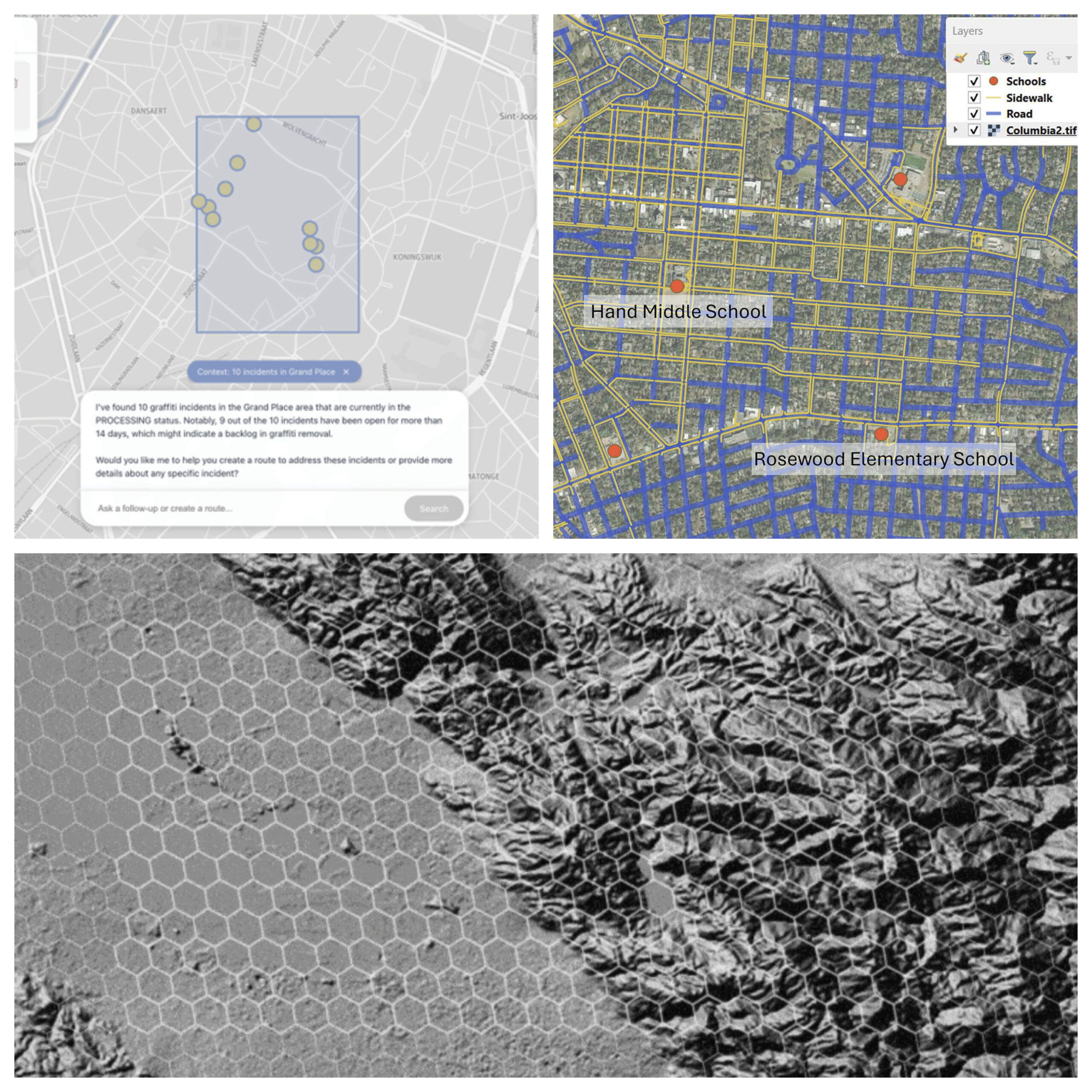

In the field of Geographic Information Systems, we can notice the rise of autonomous AI agents. A multi-institutional team led by Penn State researchers demonstrated agents capable of performing complex geospatial tasks with minimal human oversight. Their LLM-Find agent can autonomously retrieve specific geospatial datasets based on natural language prompts, while the GIS Copilot completed over 100 multi-step spatial tasks with an 86% success rate. This suggests a future where non-experts can perform sophisticated spatial analysis through conversational interactions.

Complementing this, AWS and Foursquare have introduced geospatial AI agents that enable domain experts to answer complex spatial questions in minutes instead of months. By using the H3 hierarchical spatial grid as a universal join key, these agents can combine disparate datasets – such as property insurance records and climate risk projections – without requiring custom data engineering. Similarly, the Strands Agents framework is being used in the public sector to help government workers manage incident reports and optimize resource routing through simple conversational requests.

Infrastructure Safety and Urban Resilience

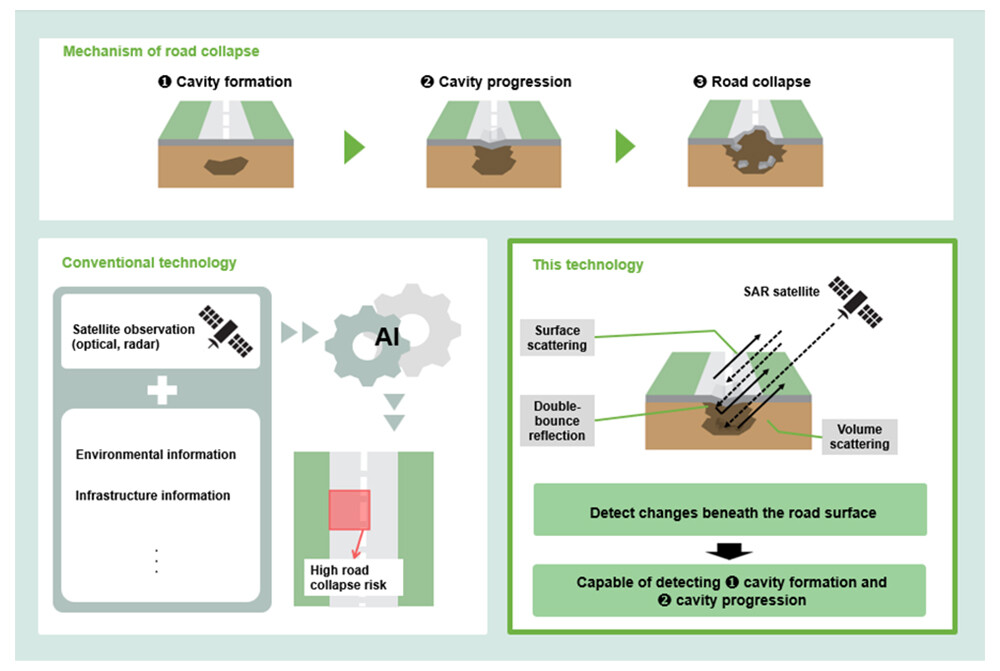

Technological breakthroughs are also being applied to immediate human safety concerns. NTT successfully demonstrated a world-first method for detecting early signs of underground road cave-ins using reflected radio waves from SAR satellites. By analyzing radio waves capable of penetrating asphalt, this technology can identify potential cavities beneath the surface without the need for on-site survey vehicles, a move expected to reduce inspection costs by approximately 85%.

In Europe, nations are deploying GIS-based noise maps to combat the “silent killer” of noise pollution, which is linked to thousands of premature deaths and an annual economic loss of $111 billion. These maps, such as those maintained by the Irish Environmental Protection Agency, allow policymakers to visualize noise hotspots – like the M50 freeway in Dublin or the Guinness Brewery – and implement infrastructure solutions like noise barriers. Additionally, an ESA-led “AI for Earthquake Response Challenge” recently recognized international teams for developing models that automate building damage detection from space, a capability critical for rapid search-and-rescue efforts.

The Evolution of Cartography and Historical Discovery

The past month has highlighted the enduring power of maps as “memory engines” that connect place and emotion. Allen Carroll, the creator of ArcGIS StoryMaps, released his new book, Telling Stories with Maps, reflecting on how the platform has enabled over 3.5 million stories to be told, ranging from Indigenous territories in the Amazon to wildlife migrations.

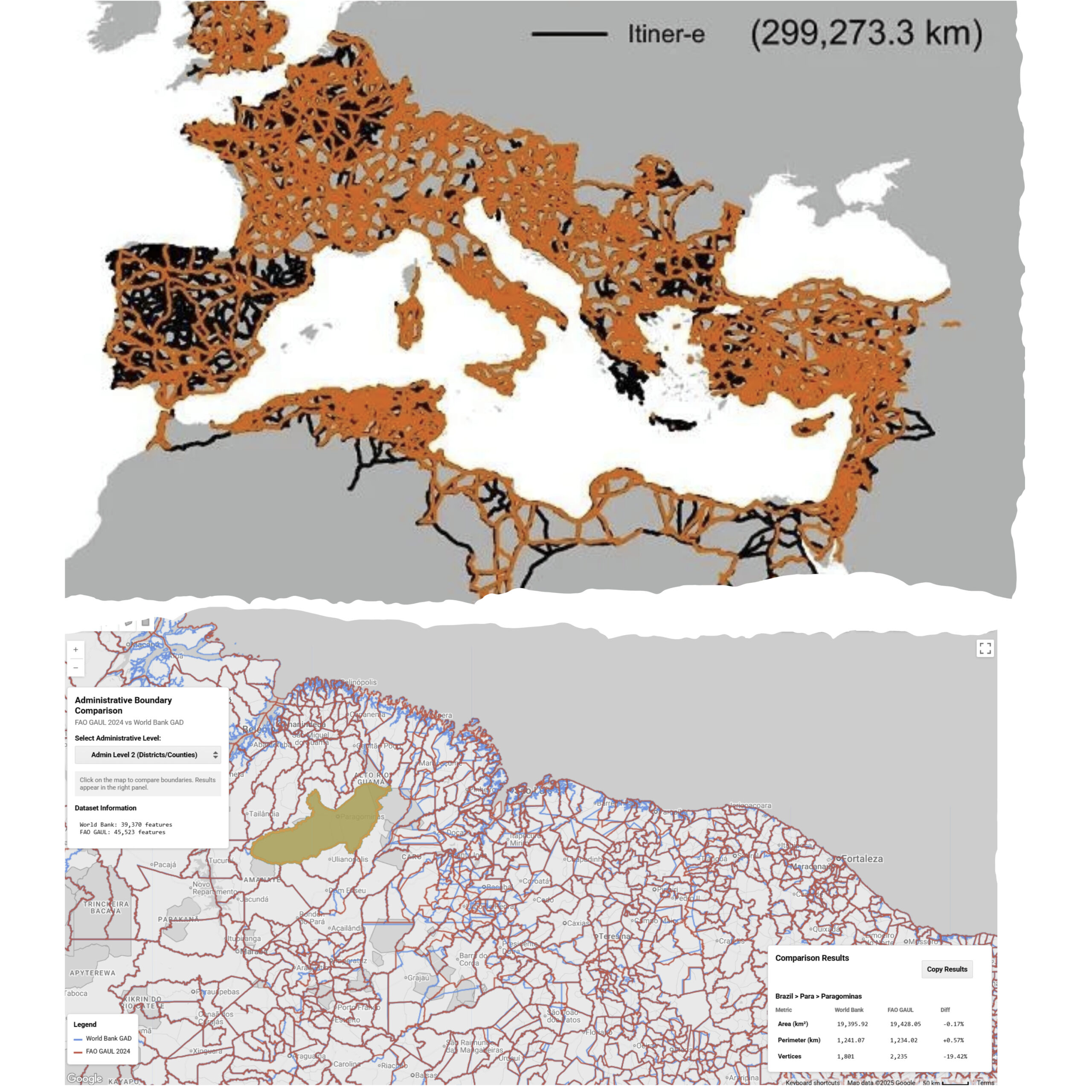

This spirit of discovery extends into our past with the release of Itiner-e, a high-resolution digital map of the Roman Empire around 150 CE. This dataset nearly doubles the previously known length of the Roman road network, documenting 299,171 kilometers of roads. Simultaneously, the World Bank has released new high-resolution global administrative boundaries as an open public good to improve the quality of subnational development research and support smarter decision-making.

In summary: Tech for Earth as a Living Digital Nervous System is becoming reality: data streams interact continuously, sensing subtle changes across the planet and enabling faster, coordinated, and informed responses.

Did you like this post? Follow us on our social media channels!

Read more and subscribe to our monthly newsletter!