The University of Groningen (the Netherlands) is one of the Dutch universities with a dedicated expertise centre for spatial data and GIS: the Geodienst (Geoservices). At the Geodienst we believe that almost all data have a spatial component, or should have one! We therefore support students, staff members and external parties with the use of GIS and spatial data, and show them the opportunities of location data. On our quest to promote the application of geospatial research to a large audience, we’ve already experienced that maps are appreciated by many, as they are received well on our social media. Additionally, we’ve witnessed that geospatial research can have a large societal impact, for on multiple occasions our analyses and maps have led to parliamentary questions. Since 2014 we’ve worked together with many students, researchers, journalists, officials and… citizens!

Citizen science is no new concept, but the subject has seen an increase of awareness in recent years. Gathering data with the help of non-specialists is an effective method in the geospatial domain as well. We want to share with you some examples of how geospatial research can benefit from citizen science, and some of the lessons we’ve learned during this process.

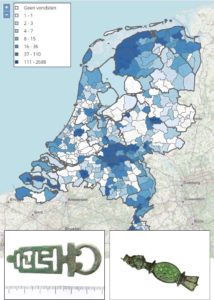

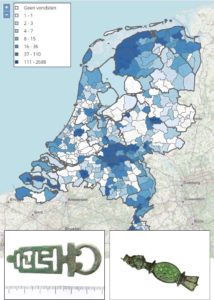

Portable Antiquities of the Netherlands (PAN)

Link: https://www.portable-antiquities.nl/pan/#/public

For a long time it was prohibited by Dutch law for non-specialists to search for, and take home, archaeological artefacts. Yet although it was not allowed, it was tolerated and happened regularly. This resulted in many archaeological finds disappearing in private collections, never to be studied by historians and/or archaeologists. Valuable information about the artefacts and the location they were found in, that could lead to a better understanding of the past, were never published or shared. Furthermore, owners of these private collections are getting older and when they’d come to pass, the archaeologically crucial information about the location of the finds would be lost forever.

However, in 2016 the Dutch law was changed, and now hobbyists are permitted to actively search for and take home archaeological artefacts at a maximum depth of 30 cm. With this new law, and the aging of private collectors, there was need for a platform to record all these privately owned artefacts. This in when the Portable Antiquities of the Netherlands (PAN) project was launched. PAN is a project of the VU Amsterdam, and was made possible by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) and Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands (RCE). The Geodienst is responsible for the technical realisation of the project. PAN is the most complete and advanced overview of Dutch archaeological finds by non-specialists. Most of the online platform is openly accessible and contains pictures and descriptions of artefacts which are linked to the location they were found in. The part of the site that is publicly available only shows the municipality in which the find was made, but researchers can request access to the restricted part of the site and view the exact location. The responsibility for adding the find(s) to the database lies with the discoverer. The artefacts are then validated by a specialists.

PAN is an example of a successful large-scale citizen science project. The database currently contains over 18.000(!) validated artefacts from private collections. More importantly, the project stimulates the interaction between specialists and hobbyists, two groups that initially didn’t speak highly of each other. PAN allows all of them to share in a fascination for history and/or archaeology, and aids archaeological and historical research.

Waddenplastic.nl

Link: https://www.arcgis.com/home/webmap/viewer.html?webmap=3eb9b39fda224e1086ce8b8ffdacf053&extent=6.0562,53.4204,6.2258,53.4812

While PAN is a large-scale project with an extensive and complex backend, the implementation of citizen science does not necessarily require such an intricate application. Depending on the goal and budget of a project, it is also possible to implement citizen science with a smaller budget and shorter time span. An example of such a project is Waddenplastic.nl.

On the 1st of January 2019, 345 containers accidentally went overboard a large container ship sailing the North Sea. The contents of the containers washed ashore on, among others, the Dutch Wadden Isles. These islands in the north of the Netherlands are listed by UNESCO as World Heritage because of their unique geological and ecological values. Especially packing materials, in the form of small and lightweight plastic granules, are a potential danger to the ecosystem of the area as they scattered across the coastline. The distribution of the plastic granules is being mapped with the help of citizen science. Inhabitants and visitors of the region share their location and the number of recorded granules on a 40 x 40 cm square. The locations and amount of granules are immediately recorded on a map available on ArcGIS online. With the help of citizens it is now possible to comprehend the spatial distribution of the plastic granules, and this information is essential in determining where targeted cleaning actions should be started. Additionally, these data are suitable for future research.

Closing thoughts

An imaginable critique on the implementation of citizen science is the possibility of fraud and/or the recording of false information. However, this concern for a loss of (scientific) integrity is unfounded, for the recording of false information does hardly occur.

The implementation of citizen science in geospatial research has great potential. The gathering of data is relatively fast, and it yields fruitful results for academic research. Additionally, the amount of enthusiastic participants shows that people like to be involved in the research based in their own area, or research about topics that interests them. Citizen science therefore also stimulates public engagement in science, and improves the public outreach value of the project.

So let’s continue to promote spatial technology for science and society!

References: