Geographers, Cartographers, Geospatial engineers, GIS professionals are usually the kind of people we would refer to as Geogeeks! But then, as location data and spatial analysis become mainstream, more and more people with a different (and colourful) background are contributing to spatial sciences and map making with their unique perspective. The quintessential offbeat Geogeeks. Hence the new series (yup, it’s a new year thing) OffBeat Geogeeks!

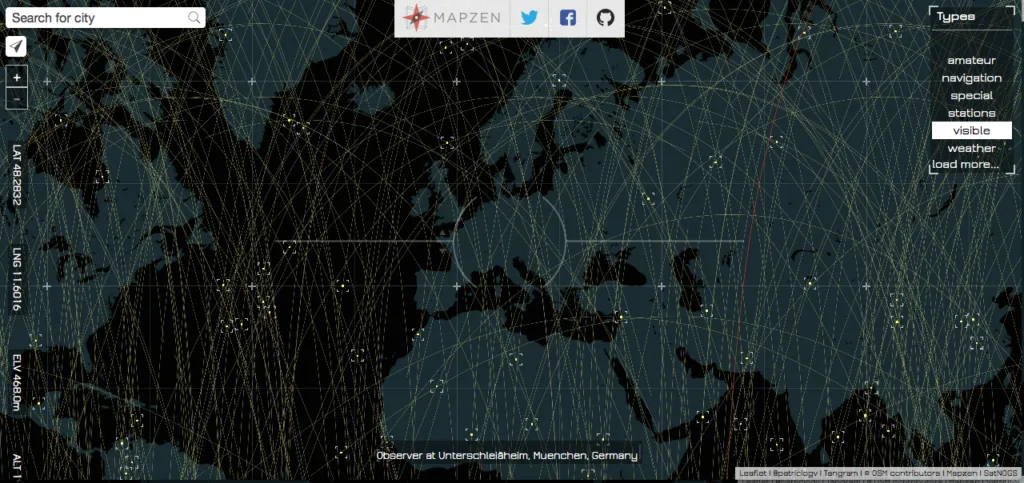

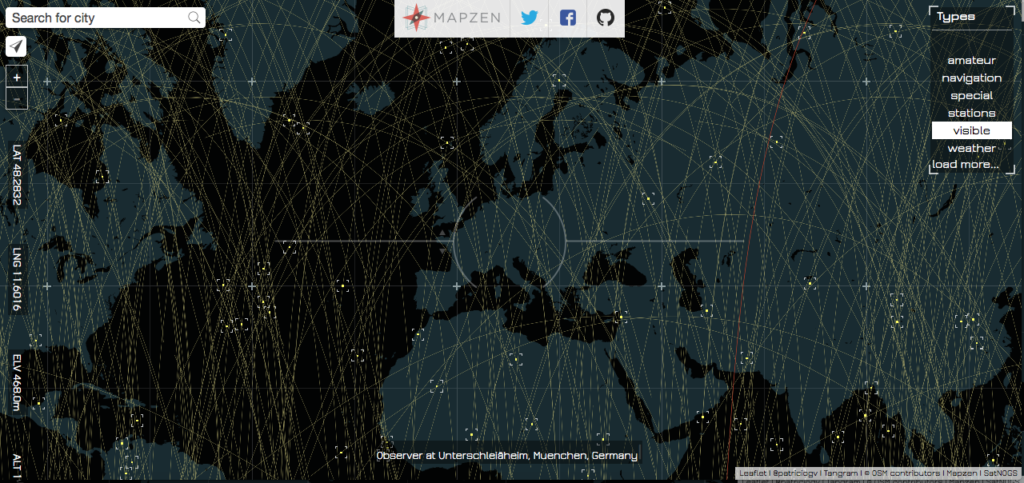

It’s really inspiring to know that people from non-geo background are just as crazy about maps as we are! One of the recent projects that really amazed me was the Line Of Sight project, where the designer visualised satellite trajectory data in a really interesting manner. The project was featured on several magazines and even people from NASA tweeted about it 😉

I had a blast talking to Patricio, the guy behind the Line of Sight project (Scroll to the bottom for more about Patricio). Patricio is currently working at Mapzen as a graphic engineer. Here’s what he had to say to Geoawesomeness.

How life at Mapzen? Do you consider yourself as a GeoGeek now that you work with a “mapping lab”?

I don’t have a geo-background. Luckily, here in Mapzen, most of the people have very uncommon backgrounds. I remember my job interview with Randy (our CEO) & Brett (our CTO) and how interested they were in my art background. I thought how cool it was that Mapzen was really interested out of the box perspective to make a mapping lab. For me is the equivalent of working in the original Bell labs, where we have lot of freedom to push the boundaries of mapping.

Line of sight is an amazing project. What was it that attracted your attention to tracking and visualizing satellites?

I have been interested on the subject of landscape for a while. One of the things that most seduce me about it is the scale and complexity of it, to the point that our perception need assistance to really perceive what’s really going out out there. That’s where technology becomes a prosthetic medium of perception.

Recently I become interested on radio frequencies, this “old” and omnipresent technology is invisible to our sense but influence almost every aspect of our life. Radio waves is an essential part of our modern life, we use it constantly but never in a direct way. I was excited to discover that most satellites can be seen with naked eyes at nights, and also is not to hard to communicate with them. So I decide to make a tool that helps discover if a satellite is on the line of sight and how I could listen or talk to it.

Obviously you had to write more than a few lines of code to get the Line of Sight map but one very mystical aspect was the animation 😉 Could you tell us more about the magic behind the scenes.

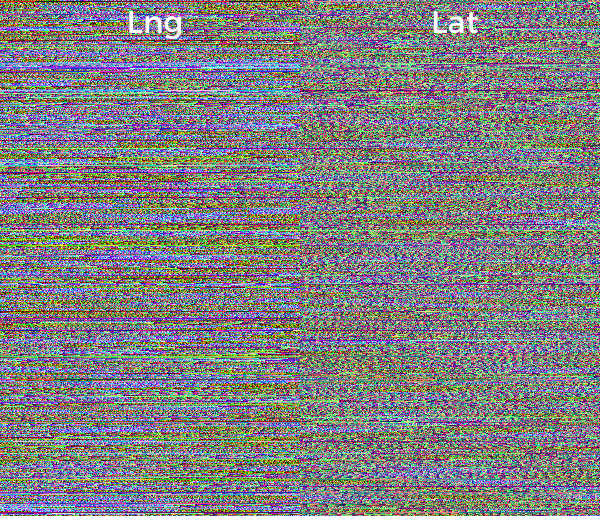

As an artist, it was very important the experience of finding this invisible objects. That’s where the idea of smoothly moving satellites become important. But there was a technical limitation I need to solve in order to smoothly display the accurate position of over 2000 satellites. For solving these I use Mapzen’s powerful and flexible 2D & 3D map engine, call Tangram. Tangram is a webGL engine designed to combine vector tiles with GLSL shaders (one of my favorite languages). The trick is based on the old-school computer graphic technique of encoding data on an image. Values (in this case coordinates) are transform into colors using the RGB channels. Satellites future positions are precompute, translated to colors and finally incorporated to a big image. These image is then loaded to the graphic card, which have parallel processing power, and can nicely animate and draw satellites for a given moment on time.

Line of Sight texture from Github

The poetic twist of this technique is that ironically the concept of “hided” information on color is not new for astronomers. As you know stellar spectra, use the color spectrum of the light coming from a star to determine the composition of it.

Talking about programming, you mentioned that you are a self-taught programmer (P.S: he has a degree in clinical psychology). What was the motivation behind the move and where did you start?

I always like to figurate out how things work. I guess my past life as a clinical psychologist, was motivated by trying to understand us. I like to experiment a lot, so as a therapist I start learning new techniques, like expressive art therapy, which finally introduced me to arts. I discover a community of brilliant and generous artist in the field of new media. They were making different frameworks to do art with computers. I got hooked immediately! I teach my self how to code using Processing and openFrameworks. Both libraries, are easy to learn and have huge communities around them. I start with Daniel Shiffman’s Learning Processing orange book, then I spend a lot of time on OpenFrameworks Forum, learning C++. I believe I have had millions of teachers for different part of the world that barely knows they have been important in my career. That’s why I have a big appreciation of openSource initiatives.

The community plays an important role in Open Source. Is that what makes you work on Open Source projects?

Definitely YES! I’m very lucky to be part of Mapzen. We are all-in for open source. I enjoy working on the open. I believe deeply on the power of it.

As a celebrated designer and Open Source contributor, whats your advice to upcoming geospatial professionals?

Stay open, keep your self in the learning zone and found others to collaborate with.

ABOUT:

Patricio Gonzalez Vivo is an artist and engineer who uses code and light to turn data into stunning landscapes. His landscapes address the problem of scale and the development of technology to perceive beyond the world in front of us. This technology helps us to see where our eyes are otherwise blind, pushing our cognitive limits. Patricio’s landscapes are not just representations of space but compositions of time and perception. Although his work is technically sophisticated his process is driven by curiosity and playful tinkering. Binoculars, telescopes, astrolabes, compasses, grids, maps, and photographs are some of the apparatus that trigger his imagination.

Patricio Gonzalez Vivo is an artist and engineer who uses code and light to turn data into stunning landscapes. His landscapes address the problem of scale and the development of technology to perceive beyond the world in front of us. This technology helps us to see where our eyes are otherwise blind, pushing our cognitive limits. Patricio’s landscapes are not just representations of space but compositions of time and perception. Although his work is technically sophisticated his process is driven by curiosity and playful tinkering. Binoculars, telescopes, astrolabes, compasses, grids, maps, and photographs are some of the apparatus that trigger his imagination.

Patricio’s work has been shown at FILE Festival (2012, 2013), Espacio Fundación Telefónica, and FASE. He was a MediaLab resident at Centro Cultural Español. Patricio currently makes open source mapping tools at Mapzen. His work has been featured inGizmodo, The Atlantic, and Fast Company. He developed visual systems for the interactive Clouds documentary. He teaches at Parsons The New School, where he received his MFA in Design and Technology.

Patricio lives in Brooklyn and Buenos Aires. In his previous life he was a clinical psychologist and art therapist. He believes in developing a better together.