New Earth Observation Business Models: From Price‑Per‑Kilometer to Insights‑as‑a‑Service

The Problem with Traditional EO Pricing Models

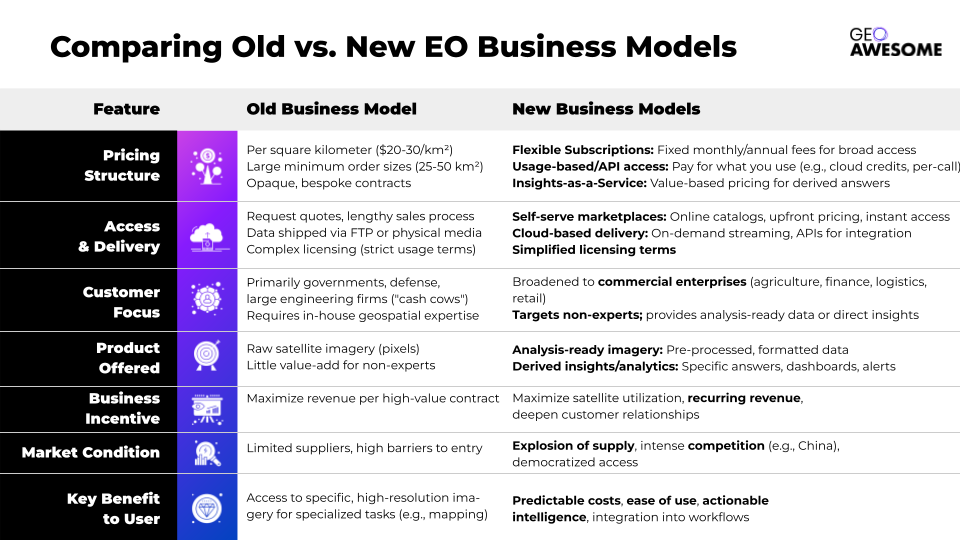

For decades, satellite imagery was sold much like land – by the square kilometer. Legacy Earth observation (EO) companies often charged on the order of $20–30 per km² for high-resolution imagery, with minimum order sizes of 25–50 km². In practice, that meant a customer might have to spend $500–$1,000 or more even if they only needed a single snapshot of a small area. This price-per-kilometer model, born in an era when governments and militaries were the primary buyers, came with strict licensing and sizable minimum buys to protect providers’ revenue. It worked for defense clients – the U.S. government, for example, has long been willing to pay top dollar for the best imagery. But for many commercial and nonprofit users, it made satellite data prohibitively expensive or simply impractical.

Traditional pricing was also notoriously opaque and inflexible. For a long time, vendors did not even publish price lists online – interested buyers had to request a quote and navigate a sales process, factoring in archive vs. new tasking fees, resolution, licensing terms, and more. Each contract was bespoke. This lack of transparency and standardization kept new, smaller customers at bay, especially startups or non-expert users who found the process confusing.

Selling imagery by the km² with complex usage licenses is a remnant of the defense sector that holds little appeal for users who lack in-house geospatial teams and only require the derived product or information. In other words, outside of government, defense and engineering firms, raw imagery on these terms brought limited value.

From a business standpoint, incumbent satellite operators long relied on big government contracts as “cash cows.” These multi-million dollar deals (e.g. a 10-year, $3+ billion contract that Maxar received from the U.S. National Reconnaissance Office) guaranteed revenue. With such clients footing the bills, companies had little incentive to overhaul pricing structures or risk cannibalizing their high-margin sales. Indeed, industry veterans admit that legacy providers grew “reluctant to change their pricing” so as not to conflict with key government customers. The downside is that these inflexible models became a barrier to wider adoption of EO data in the enterprise market. A business that might benefit from satellite insights – a farm co-op, an insurance firm, a supply chain manager – often couldn’t justify the cost or hassle under the old model.

Technical barriers compounded the issue. Purchasing imagery by itself requires handling large files and performing GIS or remote sensing analysis – tasks beyond the scope of many potential end-users. A company interested in, say, tracking forest change didn’t really want gigabytes of raw pixels; they wanted to know “how much deforestation occurred in my supply area this month.” The traditional model didn’t cater to that need for actionable information. All of these challenges set the stage for new approaches to emerge.

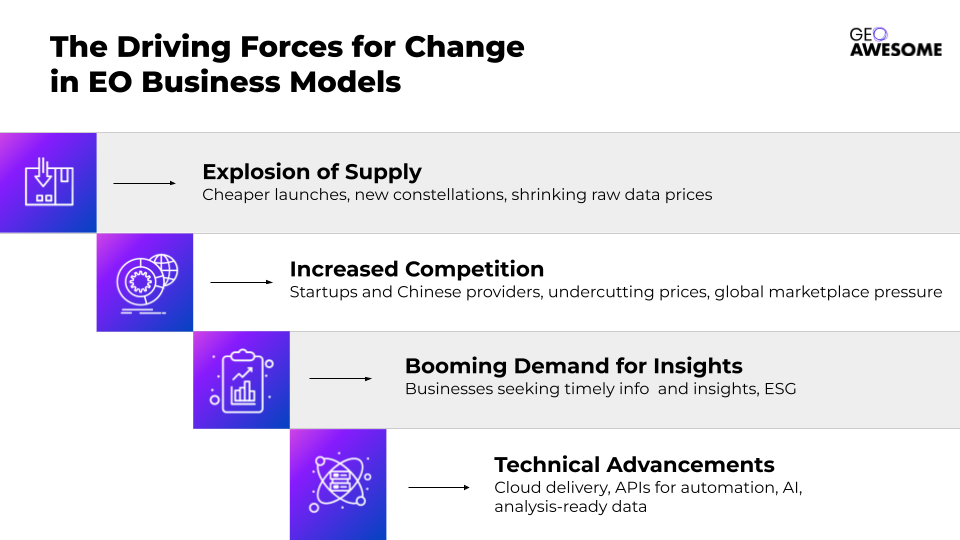

Pressure to Change: More Satellites, More Data, More Demand

Several trends in the last few years have forced the EO industry to rethink its business models. First is the explosion of supply. Thanks to cheaper launches and smaller satellites, dozens of new EO constellations have been put into orbit. Companies like Planet, for example, deployed hundreds of microsatellites, flooding the market with daily images of Earth’s entire landmass. This radical increase in available imagery (and the entry of many new players) has begun to shrink the price of raw data – the old high-price paradigm became less tenable when newer constellations offered lower-cost or even freemium imagery. An industry that once had only a handful of suppliers now has a glut of data from optical, radar, and other sensors.

Competitive pressure is coming not just from Western startups but also international providers – especially China. Chinese companies have launched high-resolution satellites (such as the SuperView and Jilin constellations) and are aggressively seeking clients abroad. They’re often willing to offer comparable imagery at significantly lower prices. For instance, China’s SuperView-1 satellites (50 cm resolution) sell imagery for as little as $14 per km², undercutting the typical $20–$25+ per km² Western rate. This price competition means that if American or European vendors stick to old pricing, they risk losing customers to cheaper foreign alternatives. As one security analyst warned, Chinese firms that become the low-cost “partner of choice” for satellite imagery could “undercut [US and EU] companies in the global marketplace” – a scenario that also carries geopolitical implications, since whoever controls the imagery supply can influence the narrative in international crises.

At the same time, legacy providers themselves have been expanding capacity, launching new, more advanced satellites. Maxar’s WorldView Legion constellation (finally launching after delays) and Airbus’s Pléiades Neo are bringing more 30 cm-class sensors on-line. More satellites in orbit inherently mean more imagery supply – and an imperative to keep those satellites busy. An EO satellite costs a fortune whether its images are sold or not; every pass it makes without a customer is lost revenue. This is pushing providers toward models that maximize utilization, even if that means charging less per scene or finding new types of customers. As one observer quipped, a satellite image is a perishable resource – like an airline seat on a flight – once the moment passes, you can’t sell it later. This mindset is driving more flexible pricing schemes.

Another catalyst is the booming demand for timely geospatial information in various industries. Sectors like agriculture, finance, and logistics have started to see the value of EO data, especially as big topics like sustainability and climate risk move to the forefront. But these new users aren’t traditional imagery experts, and they won’t come online under the old buy-your-own-imagery model. The EO industry recognizes that to capture enterprise demand, it must provide data in more accessible, user-friendly ways. In short, the world wants more satellite-driven insights than ever, but on different terms – and both upstart and incumbent providers are responding.

Emerging Business Models: Toward “Imagery-as-a-Service”

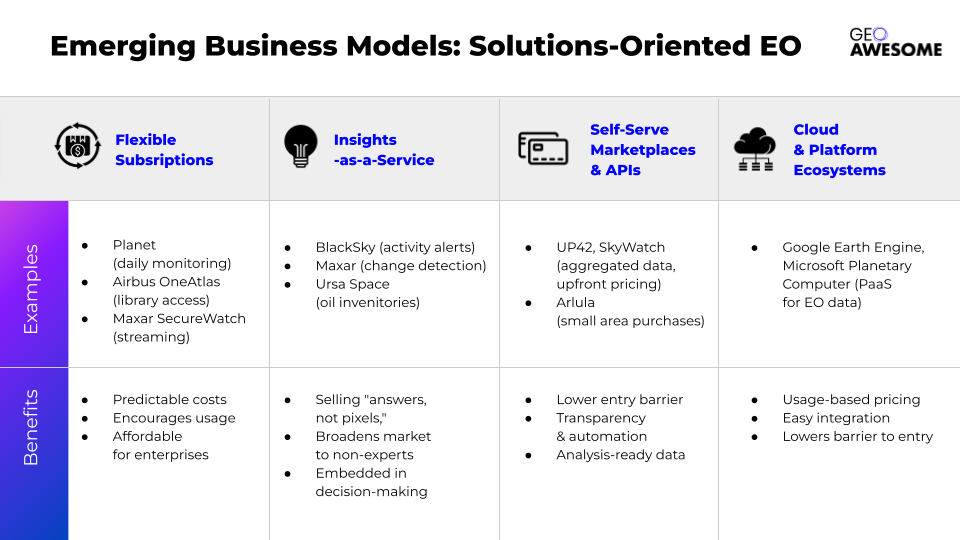

1. Flexible Subscriptions Instead of One-Off Sales

One of the biggest shifts has been moving from transactional sales to subscription models. Rather than buying imagery scene by scene (with unpredictable costs), customers can now pay a fixed monthly or annual fee for broad access to a pool of data. This ensures predictable costs and encourages usage. Several leading vendors have rolled out subscription offerings in recent years:

- Planet offers subscriptions for daily monitoring. A client can subscribe to Planet’s platform to get frequently-updated imagery (3–5 m resolution) over their areas of interest without limit on the number of images. Higher-resolution 50 cm SkySat images can be accessed on demand as a premium add-on, creating a tiered service model.

- Airbus has its OneAtlas Living Library, a subscription that unlocks multi-resolution optical imagery (SPOT 1.5 m, Pléiades 50 cm, and the new 30 cm Pléiades Neo) including decades of archives. Rather than buying individual scenes, users get a buffet-style license to Airbus’s entire data library, plus regular updates in their regions of interest.

- Maxar (DigitalGlobe) introduced SecureWatch, an online platform where subscribers can stream Maxar’s 30 cm imagery of anywhere in the world, updated frequently. SecureWatch also integrates basic analytics and tools for users. Even governments have embraced this: the NGA (National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency) now often contracts via online portals for broad access instead of ordering single images.

Importantly, these subscriptions are becoming affordable to mid-sized enterprises. In the past, only a government could spend millions on imagery annually. Now, entry-level plans for some commercial subscription services start in the tens of thousands of dollars per year – still a substantial sum, but within reach for a larger corporation or a well-funded startup. For that price, the customer gets access to petabytes of data that would have cost much more if purchased piecemeal. The result is a win–win: the provider gets recurring revenue and higher overall data utilization, while the customer gets bulk buying power and simplified, predictable budgeting.

2. Self-Serve Marketplaces and APIs

Another game-changer is the rise of online platforms that aggregate imagery from multiple sources and offer it through modern APIs. Think of these as the “App Stores” or “Netflixes” for satellite data. Instead of a user having to know which company to go to for a given imagery need (and negotiate each deal), a number of EO marketplaces now provide one-stop access:

- SkyWatch and UP42 are examples of platforms where a user can search a catalog spanning many satellites (optical, radar, etc.), see pricing upfront, and purchase or task imagery on the fly. These services often use cloud credits or standard pricing tiers to abstract away the complexity of different vendors. A buyer can get a Planet image today and a Maxar image tomorrow using the same interface and account. This aggregation lowers the entry barrier for developers and smaller organizations. It also introduces pricing competition and transparency that were previously lacking, since multiple options appear side by side. As an illustration, an analyst can use SkyWatch’s API to pull a satellite image into their application with just a few lines of code, or an agriculture startup can programmatically order imagery when their field locations hit a certain drought index – all without human intervention in the ordering process.

- Arlula and Astraea (among others) similarly provide API-based storefronts for imagery. Some even allow very small area purchases – for example, buying a few square kilometers of archive imagery for only a few dollars – which was unheard of in the traditional scheme that mandated large minimum areas. This granularity enables use cases like incorporating a quick satellite snapshot into a construction site report or a journalism piece, without breaking the bank.

These marketplaces not only make purchasing easier, they often handle data preprocessing and formatting, delivering analysis-ready data. A lot of the “dirty work” (format conversion, georeferencing, tiling) gets done in the cloud, so the customer receives imagery that’s ready to plug into GIS software or machine learning models.

It’s worth noting, however, that not all incumbent providers initially embraced the marketplace concept. Some have been cautious, fearing it could commoditize their data or disrupt existing client relationships. Complexities in licensing and revenue-sharing also needed to be sorted out for multi-vendor platforms to thrive. Despite these challenges, the momentum is toward greater interoperability. In fact, even Esri – the GIS software giant – integrated a marketplace (e.g. UP42) into its ArcGIS software, so users can directly order imagery from Airbus, Capella Space, Head Aerospace (a Chinese data distributor), and others from within their GIS workflow. This kind of integration highlights how “satellite data on demand” is becoming a reality for end-users.

Crucially, APIs are enabling automation and integration of EO data into enterprise systems. Rather than treat satellite imagery as a special, one-off input, companies can wire it into their daily operations. For example, an insurance company might set up an API feed that automatically pulls in new flood imagery for an area when a heavy rain event is detected, then triggers a claims analysis algorithm. This kind of seamless integration was exactly what the EO industry lacked in the past, and it’s key to broader adoption.

3. “Insights-as-a-Service” – Selling Answers, Not Pixels

Perhaps the most profound shift in business model is the move up the value chain: providing information or insights directly, instead of just selling the raw imagery. This is often dubbed “Insights-as-a-Service”. The idea is that many customers don’t ever need to see a satellite photo at all – what they need is the analysis derived from it (for instance, a report on how a competitor’s construction project is progressing, or an alert that a certain crop’s health index has dropped). By delivering the answer straightaway, EO companies can vastly broaden their market to include clients who have zero remote-sensing expertise.

A number of startups have led the charge in this arena. Companies like Privateer (prevously known as Orbital Insight), Descartes Labs (acquired by Earth Daily) , SpaceKnow, and Ursa Space Systems pioneered a model in which they ingest imagery (sometimes petabytes from various satellite sources), apply algorithms and AI, and output easy-to-digest insights for business users. For example, Orbital Insight famously used satellite images of parking lots to generate a retail index (counting cars to estimate consumer foot traffic), which finance firms could simply buy as a data feed. Ursa Space provides energy traders with weekly estimates of oil inventories by analyzing radar satellite images of storage tank farms – the client doesn’t need to handle any imagery, they just get the numbers. These services are typically delivered via web dashboards, APIs, or reports, on a subscription basis. In effect, they translate raw pixels into the “metrics that matter” for specific industries.

Some satellite operators themselves have pivoted to this approach. A case in point is BlackSky, a company that operates a small constellation of imaging satellites but markets itself as a geospatial intelligence provider. BlackSky’s platform can send an alert (with analytics and imagery attached) whenever it detects activity changes at a site – for example, increased traffic at a factory – allowing customers to act on the insight rather than sifting images. Similarly, Planet now offers analytic add-ons (like automated crop yield estimates or road change detection) along with its imagery platform, moving toward delivering insights instead of just pictures.

This trend hasn’t gone unnoticed by the big incumbents. Even Maxar and Airbus are increasingly pitching value-added solutions. Maxar’s website, for instance, proclaims that by combining change detection, object recognition and predictive modeling, they “deliver insights as a service” to help clients quickly identify challenges. In practice, this might mean Maxar provides a finished intelligence report or live monitoring service (e.g. monitoring illegal mining in a rainforest, and giving the client updates with annotated maps) rather than just raw imagery for the client to analyze. Airbus Defence, for its part, has partnered with analytics firms and launched projects like the Verde service for forestry analytics, signaling a move in the same direction (shifting from selling “pixels” to solving customer problems).

From a business-model perspective, Insights-as-a-Service is typically delivered in a subscription or recurring revenue format as well. Clients might subscribe to a dashboard or analytic feed (for example, “keep me updated monthly on how this list of 100 shopping malls is changing”). This smooths the revenue for providers and makes costs predictable for users – very much a SaaS-like arrangement. It also deepens the relationship with customers, since the service can become embedded in their decision-making processes.

One challenge with this model is that it requires deep understanding of customer workflows. Providers must identify which insights different industries will pay for at scale. There’s no one-size-fits-all: an agro-finance company might want drought and yield forecasts, whereas a city government might pay for automated mapping of new building construction. Companies are experimenting to find those “killer apps” of satellite data. The payoff, however, could be huge – by abstracting away all the complexity of satellite technology and delivering just the insight, EO data can reach entirely new user bases. Many end-users simply want to “ask a question and get results powered by EO data,” and the industry is slowly getting there.

4. Embracing Cloud and Platform Ecosystems

Underlying many of these new business models is a shift to cloud-based delivery. Instead of shipping gigabyte imagery files via FTP (the old way), EO data is now often hosted in the cloud, ready for on-demand access. This has enabled large tech companies to enter the fray with their own platforms, which in turn influences EO business models:

- Google Earth Engine (GEE) started as a free tool for scientists and NGOs to analyze huge geospatial datasets (like Landsat and Sentinel imagery) in the cloud. It familiarized a generation of users with the idea that geospatial data can be accessed and processed on-demand without one-off purchases. Google has since commercialized Earth Engine as well, offering it as a paid service for enterprise customers within Google Cloud. That means companies can build applications on Earth Engine’s platform and pay by usage (for compute and some premium data) rather than handling raw imagery themselves – effectively a Platform-as-a-Service model for satellite data.

- Microsoft’s Planetary Computer similarly hosts a vast catalog of open EO datasets (and even some commercial data in partnership with providers) in Azure cloud, providing APIs for data discovery and analysis. Developers and startups can prototype geospatial solutions without any upfront data costs, then scale up on Azure if they find a market. This lowers the barrier to entry – you don’t need to buy imagery to start using imagery. It’s driving a culture where new EO applications expect data to be available “as a service” (often via a few API calls).

While Google and Microsoft aren’t selling satellite imagery per se, their cloud platforms are reshaping expectations. They encourage subscription or usage-based pricing (pay for what you use) and make it easy to integrate satellite data with other enterprise data streams. For EO companies, plugging into these ecosystems (through partnerships or marketplace listings) can be a business model boost in itself. For example, if an EO analytics company gets its product listed on the Azure Marketplace or AWS Data Exchange, enterprise customers can subscribe through a familiar channel, and the cloud provider handles the billing and delivery.

How These New Models Drive Enterprise Adoption

The shift from rigid, data-heavy transactions to flexible, service-oriented models is making satellite data far more accessible to enterprise users. Here are a few key impacts and remaining challenges:

- Lower Barriers, More Users: A company that once balked at spending $100,000 on imagery and hiring a remote-sensing expert can now, for example, subscribe to an “insights” service for a few thousand a month or integrate an imagery API for pennies per use. This significantly broadens the customer base. Industries such as insurance, agriculture, mining, logistics, and retail – which historically did not directly buy lots of satellite imagery – are increasingly adopting EO solutions via these new models. The focus on delivering value (e.g. “count my assets”, “flag risks for me”) means businesses can justify the expense as it ties directly to their KPIs and decisions. We’re essentially seeing EO data go from a niche product to a more mainstream business intelligence input.

- Faster Decision Cycles: By embedding satellite-derived insights into regular workflows, enterprises can respond faster to changes on the ground. For instance, an energy company might use a subscription service that alerts them if new construction appears near their pipelines (indicating potential encroachment). In the past, they might have commissioned a one-time study or purchased imagery sporadically; now it’s a continual monitoring feed. This “always-on” paradigm is only feasible because pricing has shifted from per-image to all-you-can-eat or subscription models. It encourages customers to treat satellite data as a steady resource rather than a special occasion tool.

- Higher Satellite Utilization: From the providers’ perspective, these models help ensure their expensive orbital assets are fully utilized. Instead of letting imagery go unsold (or not even capturing it due to lack of immediate orders), a subscription or API model means someone, somewhere is likely using any given bit of coverage – if not as a raw image, then as part of an analytic product. This drives up overall revenue and spreads the cost of satellite operations across many more customers. It’s analogous to how streaming services maximized the value of a film library by shifting from per-DVD sales to subscription access. In EO, a fruitful outcome of this is that even 30 cm high-resolution imagery – once used almost exclusively by military clients – is finding its way into civilian applications, because providers found new ways to package it at scale.

- Incumbents Balancing Old and New: Traditional players like Maxar and Airbus are in a transitional phase – they are adopting new business models while still catering to legacy clients. They are unlikely to abandon the classic large-contract model (governments still sign big multi-year deals for assured access to imagery). However, to compete in the burgeoning commercial market, they’ve launched parallel offerings (web platforms, analytic services, developer APIs) as discussed. Internally, this can be a culture shift – e.g., sales teams used to million-dollar single sales must adjust to smaller, volume-driven deals. We can already see a change in mindset: where older contracts focused on square kilometers delivered, newer ones focus on metrics like number of subscribers, retention, usage rates of a platform. Over time, as revenue from commercial and enterprise clients grows, the hope for these firms is to be less dependent on a handful of government “big fish.” In fact, the new models can complement the old: archive imagery paid for by governments can be repurposed and resold to commercial users via subscriptions, essentially monetizing assets multiple times.

- Continued Challenges – One Size Doesn’t Fit All: Despite the promising developments, there are challenges ahead. Enterprise customers still need education and confidence-building. Some companies may be hesitant to rely on third-party analysis (what if the “insight” is wrong?). Providers must back up their services with validation, offer transparency into how insights are generated, or allow users to drill down to the raw data when needed for verification. Initiatives to establish quality standards for automated geospatial analytics are underway to address this concern. Additionally, while many use cases have been identified, the EO industry must find scalable solutions that can be deployed to many customers, not just custom analyses for each client. This is where a lot of startups are experimenting – from monitoring supply chain deforestation to predicting retail foot traffic – figuring out which products have repeatable market demand.

- Competition and Price Pressure: With an influx of providers (and especially the lower-cost entrants), there is ongoing pressure to keep prices competitive. We may see further price drops or innovative pricing (e.g. pay-per-insight pricing, or success-based pricing) in the future. There’s also the possibility of consolidation – not every small EO company will survive, and some may merge or be acquired (as seen with UP42 being acquired in 2024, for example). The giants, meanwhile, have to continue justifying their value by offering the best quality and reliability, or by bundling unique capabilities (like very high resolution or a decades-deep archive) that newcomers can’t match. The increased supply – including dozens of Chinese satellites flooding the market with imagery – means old pricing models simply won’t hold. Even defense agencies are encouraging commercial providers to adopt new approaches so that the dual-use (military and commercial) market flourishes, ultimately to the benefit of national security as well.

In summary, the evolution of EO business models – from selling pictures by the pixel toward providing information-as-a-service – is making satellite data a far more mainstream and powerful tool. The industry is not fully transformed yet, but it has undoubtedly reached a tipping point where flexibility, openness, and user-centric services are the new norm. As legacy players and startups alike navigate this change, the ultimate beneficiaries will be the end users across the globe who can finally tap into the literally astronomical value of Earth observation.

A New Era for “Geoawesome” Business Models

It’s clear that the future of Earth observation will look very different from its past. The old guard of selling single scenes with hefty price tags is fading, pushed out by demand for more accessible and outcome-driven services. In its place, a new ecosystem is emerging – one where satellite imagery is available on tap, via cloud platforms and subscriptions, and where insights derived from space are delivered in real time to the people who need them. The EO industry, under pressure from increased supply and savvy new entrants, is reinventing itself in real-time.

This shift can be likened to the broader digital transformation in tech: we’ve gone from hardware to the cloud, from licensed software to SaaS – and now from raw imagery to “Imagery-as-a-Service” and “Insights-as-a-Service.” The companies that thrive will be those that fully embrace these models. They’ll treat utilization of their satellites as paramount (maximizing the data collected and sold), even if it means rethinking cherished legacy practices. They’ll also focus on solving customers’ problems, not just selling them data. That might mean providing an API for farmers to get crop health alerts, or a subscription for a retailer to track parking lot traffic, or a platform for a city to monitor development – all without the user needing to be a geospatial expert.

As of 2025, we are well on our way into this new era. Customers are already voting with their wallets, favoring solutions that are easy, flexible, and insight-rich. Many in the industry expect an acceleration of this trend – with more partnerships (e.g. satellite operators teaming up with AI analytics firms), more marketplace consolidation, and even greater integration of EO data into everyday business tools. The endgame might be that using satellite data becomes as unremarkable as using GPS navigation or cloud storage – a ubiquitous component of the information economy.

For now, the signs of change are everywhere: from Maxar bundling analytics with imagerymaxar.com, to startups openly declaring their mission to “fix” Earth observation business models, to Chinese constellations forcing competitive pricing, to geospatial data appearing in Google’s and Microsoft’s cloud catalogs. The movement has even caught the attention of industry influencers on platforms like LinkedIn, who frequently discuss the need for EO to adopt modern pricing and delivery mechanisms in order to unlock its full potential.

In conclusion, the shift to new EO business models – be it subscription access, on-demand APIs, or insights delivered as a service – is transforming the sector from a niche, high-cost club to a dynamic marketplace of data and intelligence. This transformation is especially crucial for enterprise adoption: it’s turning satellite imagery from a difficult, pricey product into an integral, affordable part of the data toolkit for businesses large and small. And as this trend continues, we can expect Earth observation to become ever more “geoawesome,” powering decisions and innovations in ways that were simply not possible under the old regime.

Did you like the article? Subscribe to our monthly newsletter!