How a ‘fake’ map of America almost fetched Christie’s $1.2 million

A ‘rediscovered’ rare map, a million-dollar art scandal in the making, and some hawk-eyed shrew of rare-map historians that helped a premier auction house save face… No, this isn’t the plot for a Netflix thriller, it’s an incident that unfolded in London over the past few months.

Three months ago, a man claiming to be paper restorer Arthur Bruno Drescher’s relative visited Christie’s London office. He said he had found amongst his late relative’s papers a copy of German cartographer Martin Waldseemüller’s globe gores – a 510-year-old map, famous for using the word ‘America’ for the first time.

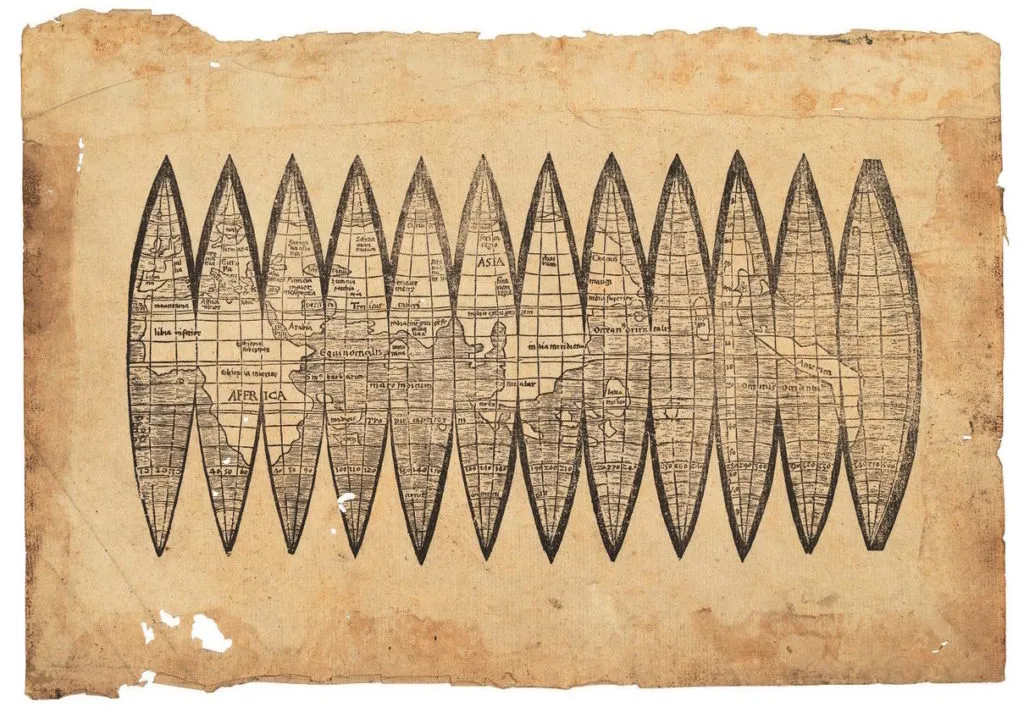

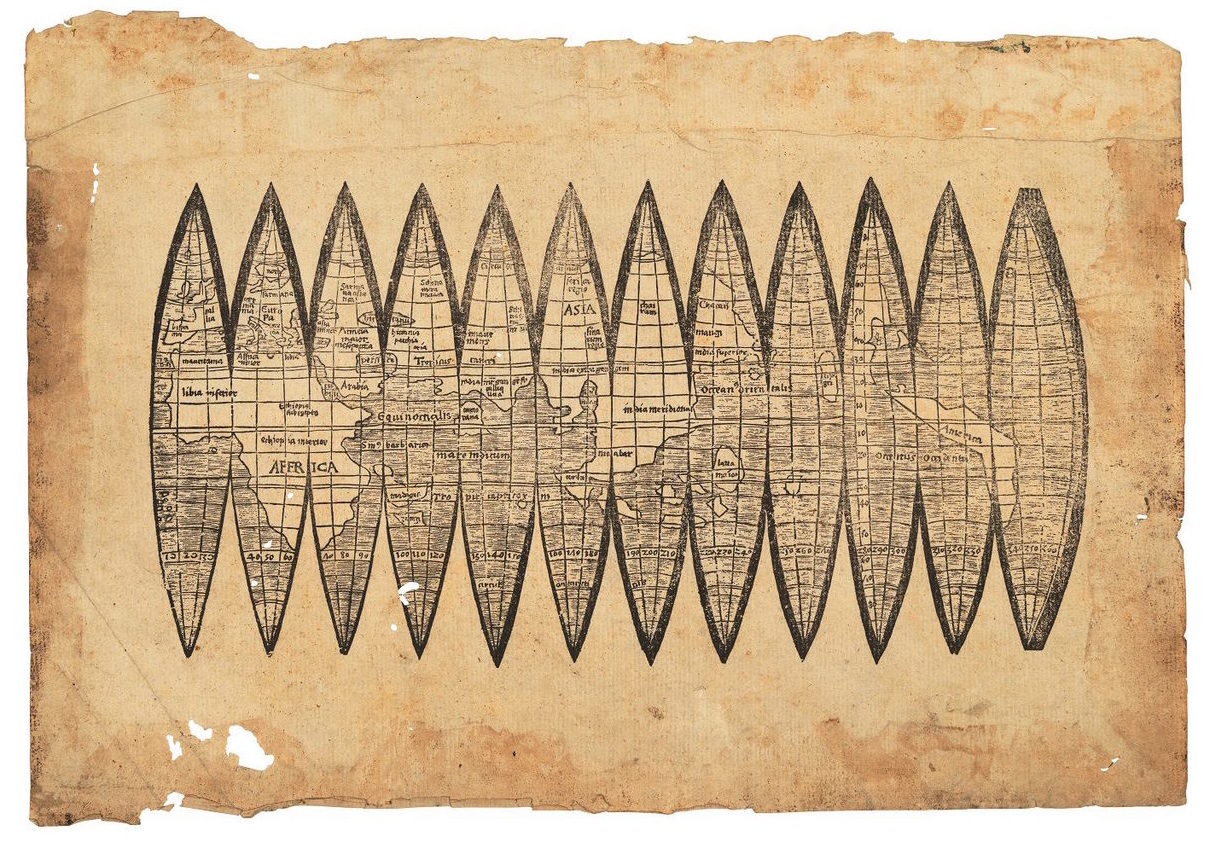

Courtesy: Christie’s

The map, printed on carved woodblocks, had ‘gores’ which are supposed to be cut out and pasted onto globes to deliver an accurate picture of the world in 360-degrees. About 1,000 copies of this map are thought to have been produced originally for a geography book, but only a handful survive – and that too because they were never cut out from the paper. Copies that were made into globes are believed to be chewed by dogs, played with by children or destroyed by fire – and permanently lost to history.

Naturally, Christie’s couldn’t believe its luck on coming across this extraordinary find. The executives at the auction house consulted their experts and visited the Bavarian State Library in Munich to compare the rare artefact with a version stored in Germany. Satisfied with what they saw, Christie’s put the map up for sale, estimating its value between $800,000 and $1.2 million.

And then came the plot twist. A group of rare map dealers and paper restorers came forward with the suggestion that the ‘rediscovered’ map was actually a forgery. These experts included a rare-map dealer working with Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps, Alex Clausen, Houston-based paper restorer Michal Peichl, and rare-book specialist Nick Wilding, according to The New York Times.

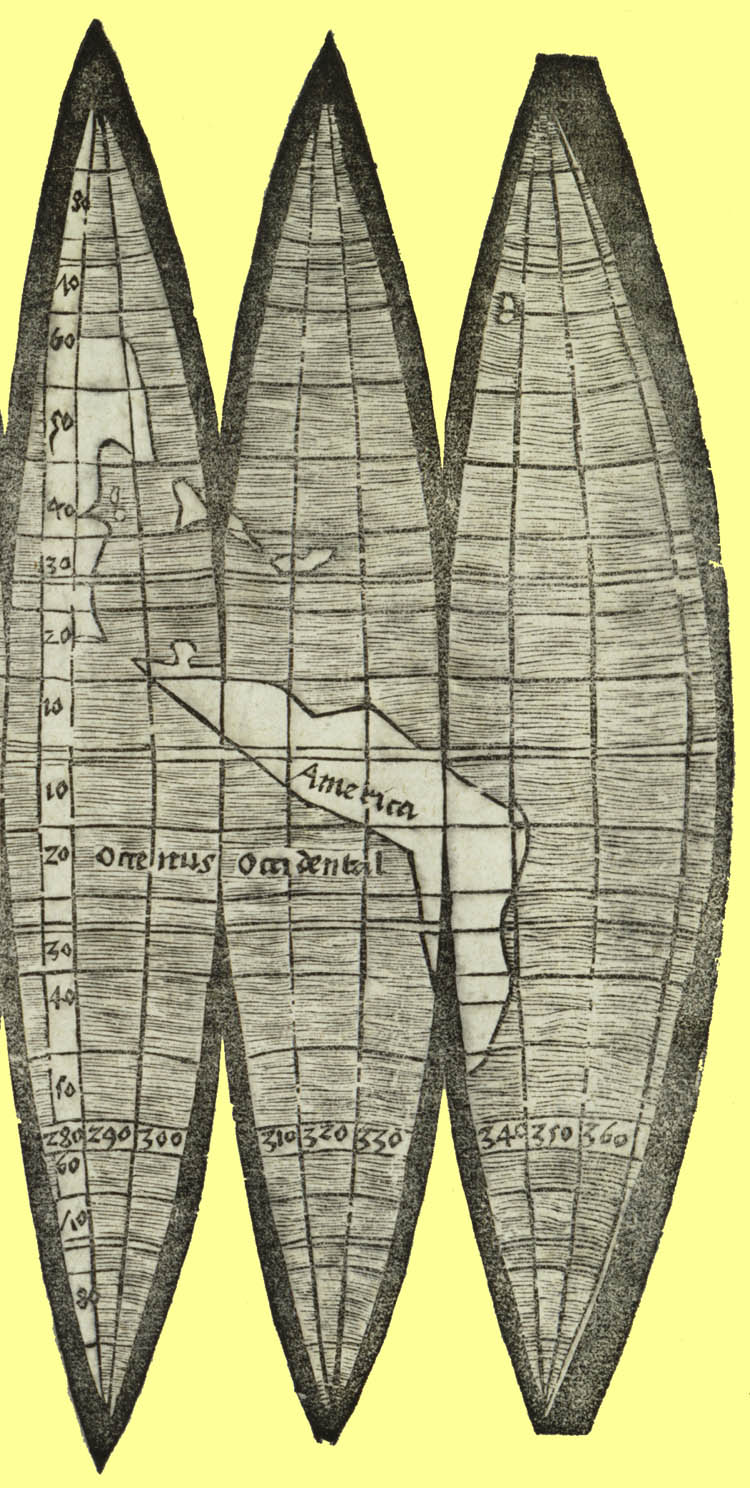

Courtesy: University of Minnesota

This group pointed out several major irregularities in the supposed woodblock-print map:

- A comparison with high-resolution pictures of the known versions of the map revealed areas in the printed image that were either etched deeper than the known copies or missing altogether.

- At one spot on the map, remnants of glue could be seen below the print – indicating that the image was printed on the page after it was torn off from a book.

- The most telling clue came in the form of a white line on the map. This line was in exactly the same place where the James Ford Bell Library at the University of Minnesota had added extra paper to their copy of the map in order to repair a tear. How could this tear be replicated in another original map?

Following these revelations, Christie’s called off the auction days before the map was supposed to go on the block on Dec 13. And here’s the thing: While the Bell Library has the authentic map which it repaired with the paper patch, the map in the Bavarian State Library also has the same white line. After discovering the turn of events at Christie’s, the library would now be reviewing the authenticity of its own map which it obtained in 1991 from the estate of renowned collector HP Kraus. The library had paid the same figure Christie’s was hoping to fetch from this map — $1.2 million.

Well, any discovery of a Waldseemüller map would have been sensational for the cartography world. After all, the map – often referred to as America’s Birth Certificate – was the first to project a fourth major landmass alongside Africa, Europe, and Asia. But it is still heartening to know that the advancements in technology have made it increasingly difficult for forgers to fool experts and auction houses with counterfeit works.