Geospatial Credit Scoring: Mapping Financial Trust through Location Intelligence

This article explores how geospatial technologies can reshape credit scoring by linking financial trust to location-based data. The goal is to show how satellite imagery, GIS, and artificial intelligence can make credit systems more inclusive, especially for people who are “credit invisible”. It also examines the ethical and regulatory challenges that come with using location data in finance.

1. The Geography of Credit

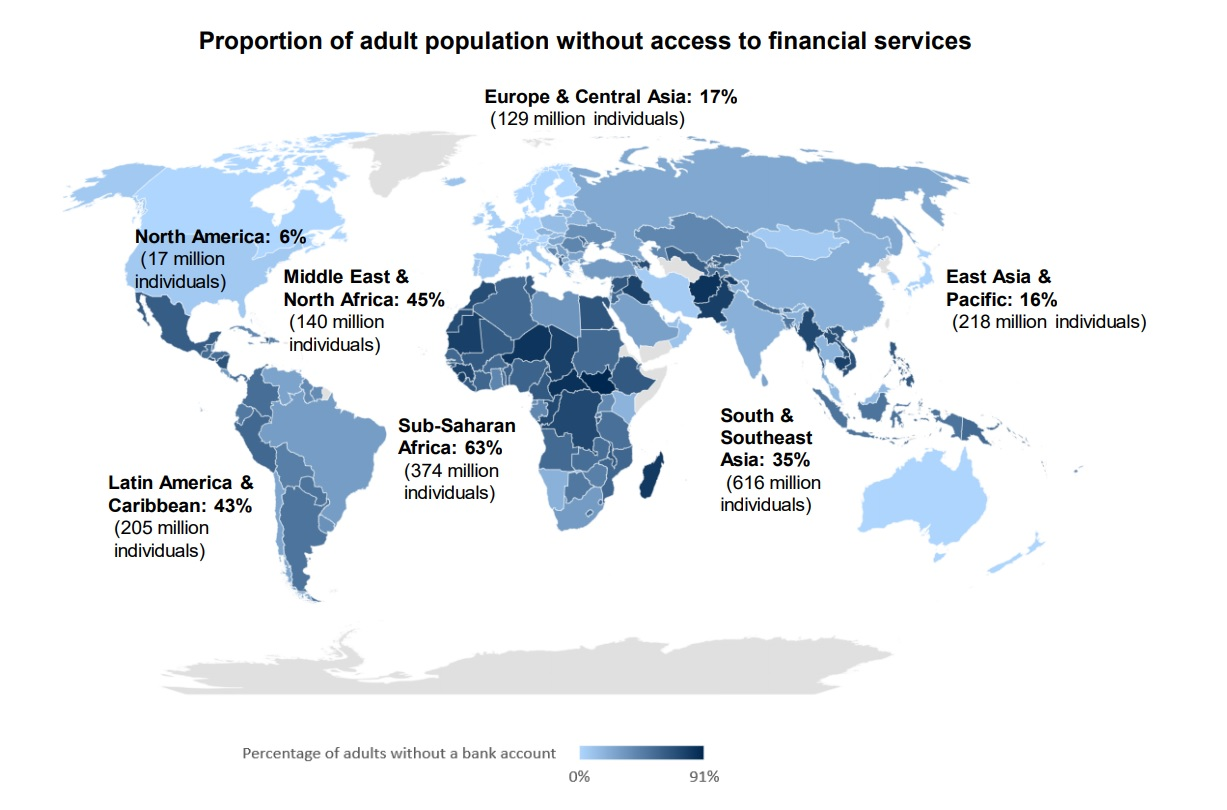

Creditworthiness has long been measured through a few financial numbers based on bank records, loans, and formal employment. Yet millions of people do not appear in these systems. About 1.4 billion adults still live without a bank account, and many others earn and spend only in cash.

These individuals are not necessarily risky borrowers. They are “credit invisible” because traditional data sources cannot capture their economic activity. The same problem affects small and medium enterprises that operate informally or lack updated documentation. This invisibility creates a financing gap that limits growth and inclusion.

Geospatial Credit Scoring (GCS) offers a new perspective. Using spatial data can reveal the environmental and social context behind financial behavior. It helps lenders see more than numbers and better understand the communities where borrowers live and work.

Proportion of adult population without access to financial services. Source: Payments Cards & Mobile

2. What Is Geospatial Credit Scoring?

GCS combines financial analytics with Geographic Information Systems (GIS), satellite imagery, and machine learning. Instead of relying only on bank records or repayment history, GCS uses data from the physical and socioeconomic environment to estimate financial stability.

Every economic activity takes place somewhere, and that location contains valuable information. Infrastructure quality, access to services, energy use, and night-time light intensity all reflect the economic condition of an area. When artificial intelligence analyzes these spatial patterns, it can help predict creditworthiness in regions where traditional financial data is limited or unreliable.

In short, GCS provides a contextual view of borrowers. It complements existing financial data by showing how local environments influence economic opportunity and resilience.

3. The Indicators That Matter

GCS relies on measurable spatial indicators that reflect local economic conditions. These signals come from open data sources and satellite imagery available for most of the world.

-

Night-Time Light Intensity

One of the most widely used proxies is night-time light intensity, captured by satellite instruments such as the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS). Areas with stronger and more stable illumination generally correspond to higher levels of economic activity. In rural or data-scarce regions, this single variable can serve as a stand-in for GDP, employment, and infrastructure quality. Researchers have shown clear correlations between night-time lights and income distribution, though the data can be noisy over short periods or in small geographies.

-

Infrastructure and Accessibility

Access to infrastructure often tells a more direct story about opportunity and risk. The density of paved roads, proximity to markets or banks, and availability of public services like schools and hospitals all influence economic stability. Borrowers who live or operate in well-connected areas generally face lower operational costs and higher resilience, making them statistically less likely to default.

-

Land Use and Property Characteristics

High-resolution imagery from missions such as Harmonized Landsat and Sentinel-2 (HLS) provides data on land use, vegetation cover, and building materials. In agriculture, for instance, satellite data helps lenders assess crop health and yield patterns, allowing them to tailor loans or insurance for farmers who lack formal collateral. For urban borrowers, land-use data can indicate property value, construction activity, and the overall vitality of a neighborhood.

-

Mobility and Economic Flow

Mobile phone metadata, where permitted and anonymized, adds another layer by revealing mobility patterns. A borrower whose phone shows consistent movement between work, home, and commercial centers may indicate stable employment. Aggregated patterns of foot traffic or digital payments can highlight local business activity, which strengthens regional risk assessments.

-

Environmental and Climate Context

Finally, geospatial models include exposure to natural hazards such as floods, droughts, or landslides. This matters not only for insurance but also for predicting credit performance, since a climate shock can affect repayment capacity even for borrowers with strong personal histories.

4. How Geospatial Credit Scoring Works

Step 1: Data Collection

Most GCS systems use open and public data sources. Satellite programs such as NASA’s Landsat and the European Space Agency’s Sentinel missions provide free, high-resolution imagery. These are combined with geodemographic data on population, road networks, and land use. Where available, mobile phone or transaction data can add behavioral insights.

Step 2: Feature Engineering

Raw satellite pixels and coordinates must be transformed into structured features, which are numbers that describe a location. Examples include average night-time light brightness, distance to the nearest market or bank, and the density of paved roads. Analysts also study how these values change over time. For instance, increasing light intensity or new building activity may signal economic growth.

Step 3: Modeling

Machine learning algorithms such as gradient boosting or neural networks learn the relationships between spatial features and loan performance. More advanced models use Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) to capture spatial relationships between borrowers or assets. If defaults cluster in one neighborhood, the model can infer contagion risk and adjust future lending behavior accordingly. In some markets, GCS models are combined with mobile phone behavioral data, such as top-up frequency or digital wallet activity. Studies have shown that combining these sources can significantly improve prediction accuracy compared to using either alone.

Step 4: Validation and Explainability

To ensure reliability, models are tested using spatial cross-validation techniques that account for geographic diversity. Explainable AI frameworks are also used to make the results transparent. Platforms, such as MSCI’s GeoSpatial Asset Intelligence, are built with transparency at their core, utilizing extensive data provenance and rigorous validation. For instance, a model can show that “proximity to major roads” or “increase in night-time light intensity” contributed most to a borrower’s score. This transparency is vital for regulatory compliance and customer trust.

5. Real-World Applications and Innovation

Emerging Markets: Credit Where None Existed

In many parts of Africa, South Asia, and Latin America, formal financial records are scarce, yet mobile and location data are abundant. Companies such as Tala, JUMO, and Branch use geospatial and behavioral signals to assess borrowers who lack credit histories.

Tala, for example, analyzes GPS consistency, travel patterns, and proximity to business hubs alongside phone and transaction data. This approach has supported more than a billion dollars in microloans with repayment rates above 90 percent. JUMO and Branch use similar models to estimate borrower stability based on movement and spending patterns.

These systems show that economic behavior leaves a spatial footprint. A small shop owner in Nairobi or Dhaka may not appear in financial databases, but satellite and mobile data can reveal the health of their business environment and community.

Agriculture and Small Business Lending

Geospatial analytics also improve access to credit in agriculture and small enterprises. Remote sensing can monitor crop health, detect droughts, and estimate yields before loans are issued. For urban or peri-urban businesses, factors such as road density and nearby schools or markets help indicate customer demand and growth potential.

Public Sector and Development Finance

Institutions such as the World Bank and UN Development Programme (UNDP) use spatial data to identify underserved communities and design financial inclusion programs. Private platforms like Atlas AI and GeoAnalytics Africa integrate satellite data with socioeconomic modeling to produce neighborhood-level indicators of wealth, risk, and opportunity.

6. Regulation and the European Perspective

In Europe, the main challenge for geospatial credit scoring is not technical but legal. The European Union places strict limits on how automated systems can influence financial decisions.

The German Example

Germany’s credit system is led by SCHUFA, the country’s main credit bureau. In December 2023, the Court of Justice of the European Union ruled that SCHUFA’s automated decision-making falls under Article 22 of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). The court decided that any automated decision that significantly affects a person’s access to credit must include human oversight or explicit consent. This ruling sets a strong precedent across Europe.

The EU Artificial Intelligence Act

The upcoming EU AI Act strengthens these protections. It classifies AI systems used in credit scoring as “high risk” and requires bias testing, transparency, and human accountability. Any system that resembles social scoring or results in discrimination is prohibited.

For lenders, this means geospatial features can be used to visualize and manage risk, but they cannot be the sole basis for automated lending decisions. Human review remains essential.

7. Ethical and Privacy Considerations

Geospatial data is incredibly powerful, but it can also be deeply personal. The places people visit, the neighborhoods they live in, and the routes they take reveal intimate details about their lives. Used irresponsibly, this data can enable surveillance or discrimination.

Data Sensitivity

Location data must always be anonymized, aggregated, and stored securely. Borrowers should know how their data is collected and used. They must also have the option to refuse automated profiling or request human review of credit decisions.

Bias and Fairness

Even when demographic factors such as race or gender are excluded, geography can act as a proxy for inequality. Poorer areas may have weaker infrastructure or lower night-time light intensity, which could bias a model against their residents. Developers should conduct fairness audits to check for uneven performance across regions and income levels.

Transparency and Explainability

Borrowers have the right to understand why they were approved or denied credit. Explainable AI frameworks make this possible by identifying the most influential spatial features, such as road access or infrastructure growth. Transparency builds trust between lenders, regulators, and customers.

8. The Road Ahead: Promise and Practical Reality

Geospatial Credit Scoring offers major potential but also significant challenges. Its success will depend on how well institutions balance innovation, regulation, and ethics.

Opportunities

GCS can expand financial inclusion by using open, verifiable data to assess borrowers who lack formal credit histories. It strengthens risk management by revealing spatial patterns of stability or stress and supports sustainable finance through a better understanding of climate and environmental risks.

Challenges

Building reliable GCS models requires technical skill, quality data, and strong governance. Satellite information can be inconsistent, and privacy concerns remain high. Regulatory frameworks such as the EU’s GDPR and AI Act add complexity, while many traditional institutions are slow to adopt data-driven systems.

The Way Forward

The most practical path is hybrid adoption, where GCS complements existing credit methods. Pilot projects in agriculture, small business, and development lending can demonstrate value while minimizing risk. Regulators can encourage experimentation through innovation sandboxes and clear guidelines.

As data quality improves and AI becomes more transparent, geospatial intelligence is likely to become a standard layer of credit analytics. It can help create fairer, more inclusive, and more sustainable financial systems.

The future of credit may well be written in coordinates. Geospatial credit scoring is still young, but its direction is clear. It reminds us that economic opportunity is not just about numbers; it is about context. If we use it responsibly, balancing precision with privacy and efficiency with empathy, it could transform how the world defines financial trust.

Did you like this post? Read more and subscribe to our monthly newsletter!