From Gatekeeper to Enabler: Shifting the Role of GIS Professional

“I want to get most of my team out of QGIS.” This is what I recently heard from a GIS specialist working for a property development company. When I asked why, he said, “There are higher training priorities – and I am tired of explaining functionality they don’t need.”

His frustration captures a dilemma facing many organizations. When spatial questions require specialist tools, GIS professionals often face an impossible choice: spend their time training colleagues on software that is too complex for their needs, or become the bottleneck by handling every spatial request themselves.

The industry often frames this as a tooling problem. The real issue is role definition.

The Specialist Trap

Research shows that only ~5% of data scientists have experience working with geospatial data. This skills gap isn’t accidental – it’s structural. Geospatial analysis has evolved as a separate discipline with its own tools, formats, and mental models, studied apart from mainstream data science and business intelligence.

This separation made sense when spatial analysis was the domain of highly trained specialists. It’s actively harmful now that spatial questions permeate every department and structure our daily lives.

Yet geospatial analysis in the workplace creates a cognitive and language barrier. GIS professionals think about coordinate reference systems, points, and polygons. Their teams think in place names and addresses. GIS works with shapefiles and rasters while traditional business analysts prefer straightforward tables with easily readable values in every cell.

Then add the technical barriers. Data preparation – already the most time-consuming and least enjoyable data science task according to industry surveys – becomes exponentially more complex with spatial data. File sizes balloon, and format conversions multiply. A typical GIS workflow involves 6-10 specialized tools, and that’s before counting the ancillary utilities needed to make them work together.

The infrastructure reflects this fragmentation. Engineers export from CAD. GIS specialists convert and reproject. Data analysts need it in their preferred BI tool. Field teams require mobile access. Stakeholders want to just skip to the bottom line. Traversing this chain once is time-consuming – but try keeping the information current on a daily basis.

The Enabler Mindset

The good news is that many GIS professionals are shifting from positioning themselves as “geospatial gurus” and gatekeepers to facilitators and enablers who make spatial analysis possible for team members.

This requires rethinking what “GIS infrastructure” means. It’s not about providing the most powerful specialist tools. It’s about identifying individual stakeholder needs and resolving both the technical and cognitive barriers that prevent non-specialists from accessing spatial insights.

Technically, this means:

- Automatic format conversions invisible to end users

- Real-time data synchronization across desktop, web, and mobile

- Processing that happens server-side, not on individual laptops

- Permissions and team management designed for cross-functional collaboration

- Geocoding built into workflows, not as a separate preprocessing step

Cognitively, this means:

- Data volumes and complexity abstracted away from users who just need answers

- Multiple entry points to the same data: specialists get QGIS, field crews get mobile apps, executives get dashboards – all synchronized

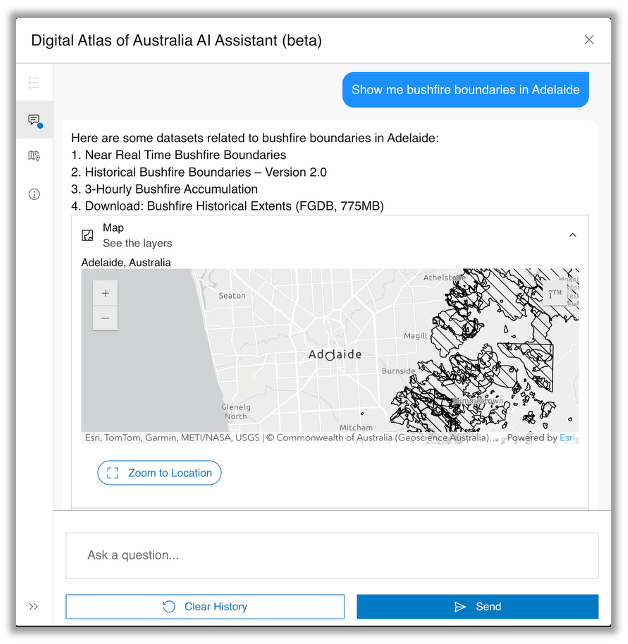

- Spatial operations presented as business questions (“Which sites are within 30 minutes of the distribution center?”) rather than GIS functions

The GIS specialist I mentioned in the introduction made this shift explicit. They moved most users to web-based interfaces while maintaining a QGIS connection for the two staff members who needed advanced capabilities. The key was real-time synchronization – field data collected via mobile appeared instantly in the desktop environment and on stakeholder dashboards. The organization maintained spatial analysis capabilities while eliminating the specialist bottleneck.

From Silos to Systems

Platforms exemplifying this integrated approach are emerging. NextGIS, for instance, connects QGIS desktop functionality with web interfaces and Android mobile apps through live synchronization. Data edited in QGIS appears immediately on a colleague’s phone. Field updates flow to interactive web maps in real-time. The GIS professional maintains control over data quality, projections, and standards while everyone else accesses what they need through interfaces matching their specific use cases.

This isn’t about replacing specialists. It’s about leveraging their expertise differently. Instead of spending the lion’s share of time producing outputs for others, GIS professionals can focus on data architecture, quality control, and sophisticated analyses that genuinely require their skills.

The organizations that will extract maximum value from spatial data aren’t those with the most GIS specialists. They’re the ones where GIS professionals have successfully engineered themselves out of answering routine spatial questions – because they’ve built systems that let everyone else answer those questions themselves.

Learn more about NextGIS at NextGIS.com.

Author Bio

With experience spanning private sector, government, and nonprofit organizations, Dmitry Nikolaev focuses on the intersection of data analysis, business process optimization, and strategic communication. At NextGIS, Dmitriy supports international market development and works with clients to align technology adoption with organizational change.