This article is part of the “Tech for Earth” series exploring the intersection of technology, sustainability, and planetary intelligence.

As we enter 2026, satellite and space technologies have moved from specialized scientific tools to essential infrastructure underpinning the global economy. Recent developments from December 2025 and early January 2026 show how Earth observation data has become central to decision-making across industries, from agriculture and urban planning to climate response and disaster management.

New Satellite Missions and Global High-Precision Monitoring

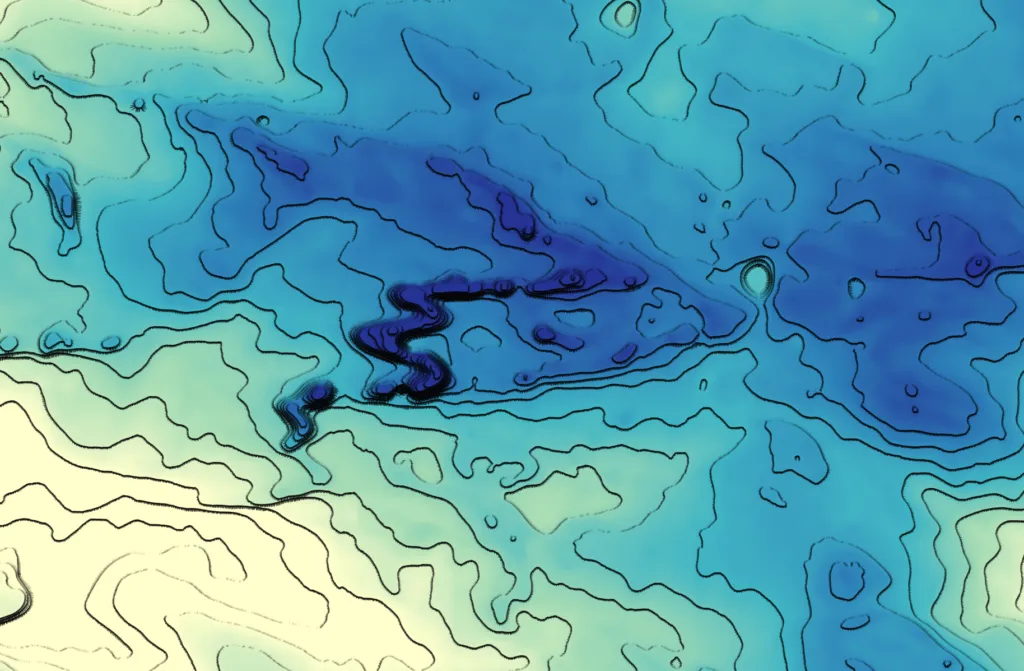

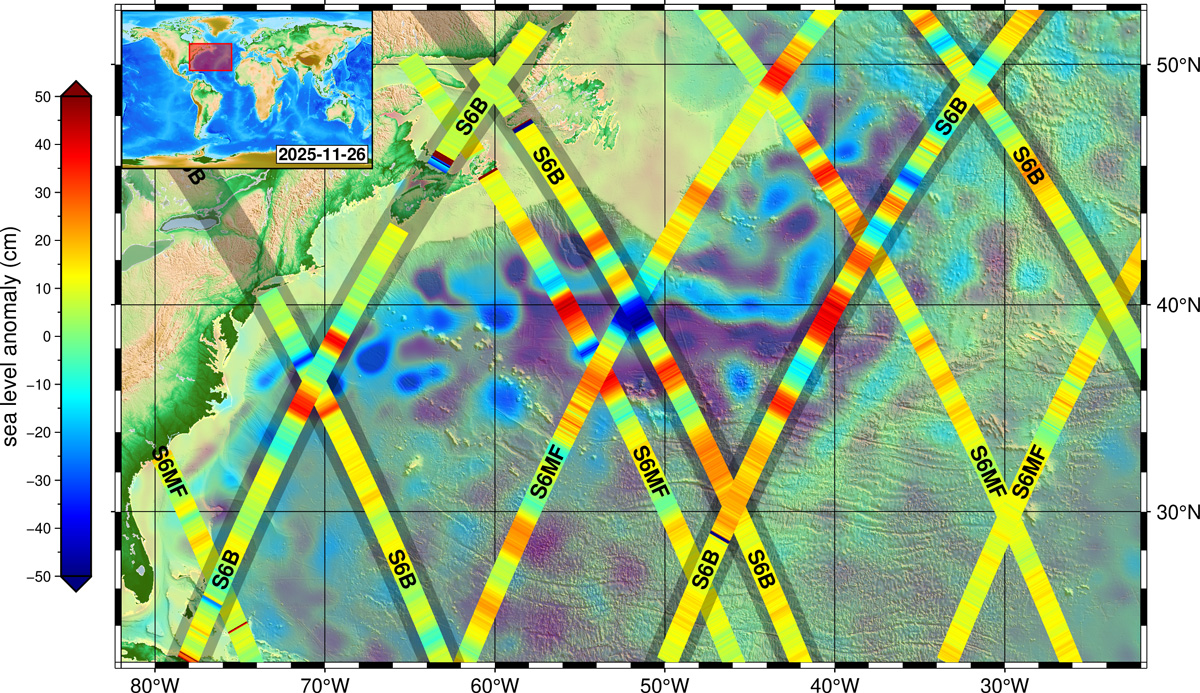

The final months of 2025 saw the launch and activation of several satellite missions. On December 16, 2025, the Copernicus Sentinel-6B delivered its first altimeter images, tracking sea-level variations in the North Atlantic with ultra-precision. Currently flying just 30 seconds behind its twin, Sentinel-6 Michael Freilich, the satellite has entered a “tandem phase” to allow for precise cross-calibration of sea-level measurements to within a fraction of a millimeter. This mission serves as the “gold-standard” reference for monitoring global sea-level rise, which is currently averaging 4.3 millimeters per year.

Altimeter measurement by Sentinel-6B and Sentinel-6 Michael Freilich

Meanwhile, the Sentinel-5 mission has begun a new era of air-quality monitoring, providing detailed maps of pollutants such as nitrogen dioxide and sulphur dioxide. In the commercial sector, Vantor’s WorldView Legion constellation is now fully operational, capable of collecting nearly 7 million square kilometers of imagery daily. Additionally, the NISAR mission has entered its science phase, deploying its 12-meter antenna to monitor river deltas and agricultural landscapes.

Mapping Innovations: 3D Models and Radical Narratives

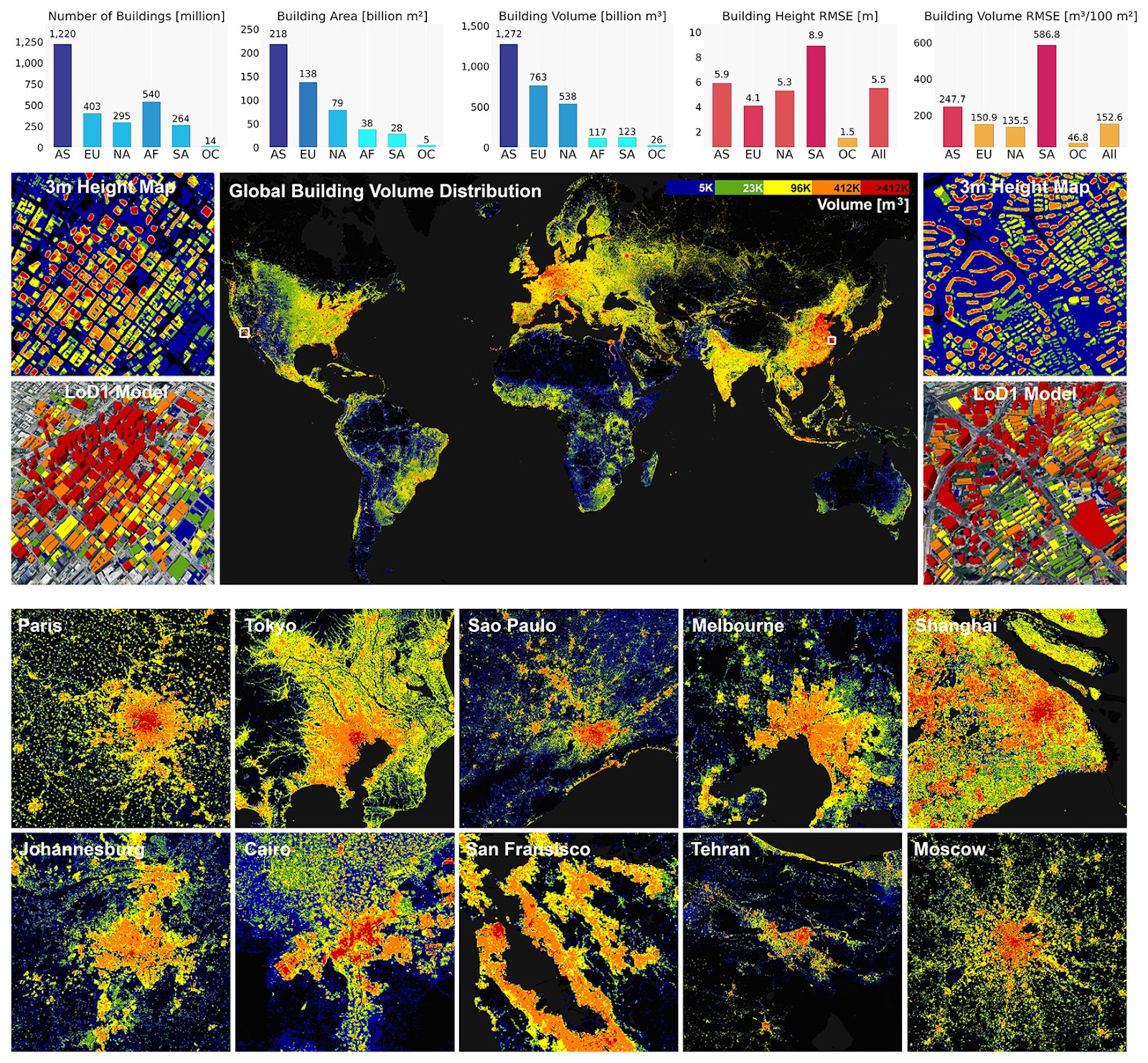

Our ability to visualize the world has been revolutionized by the release of the GlobalBuildingAtlas, a dataset capturing 2.75 billion buildings in 3D. Developed by researchers at the Technical University of Munich (TUM), this atlas provides volumetric data that offers far more precise insights into urbanization and population density than traditional 2D maps.

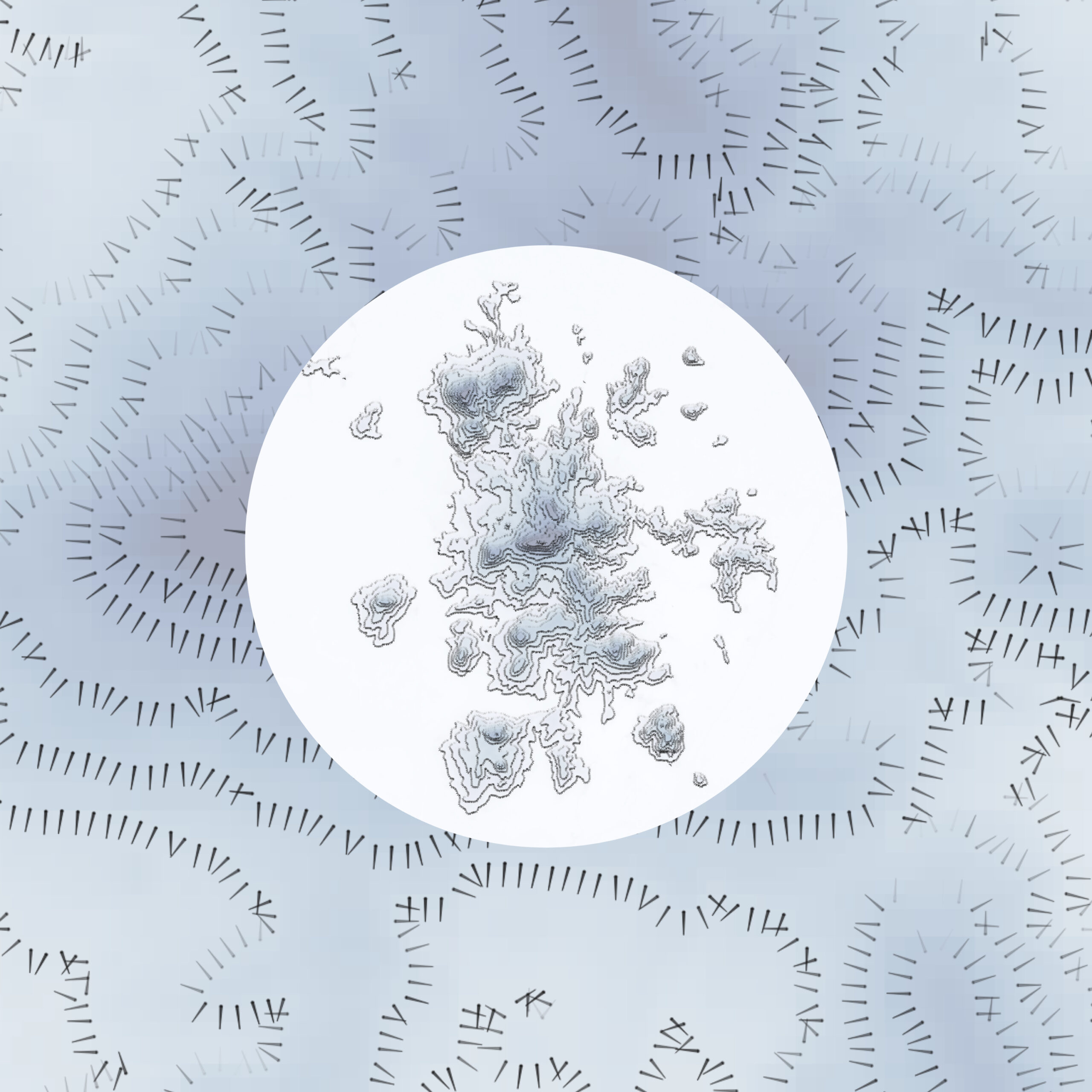

GlobalBuildingAtlas, overview

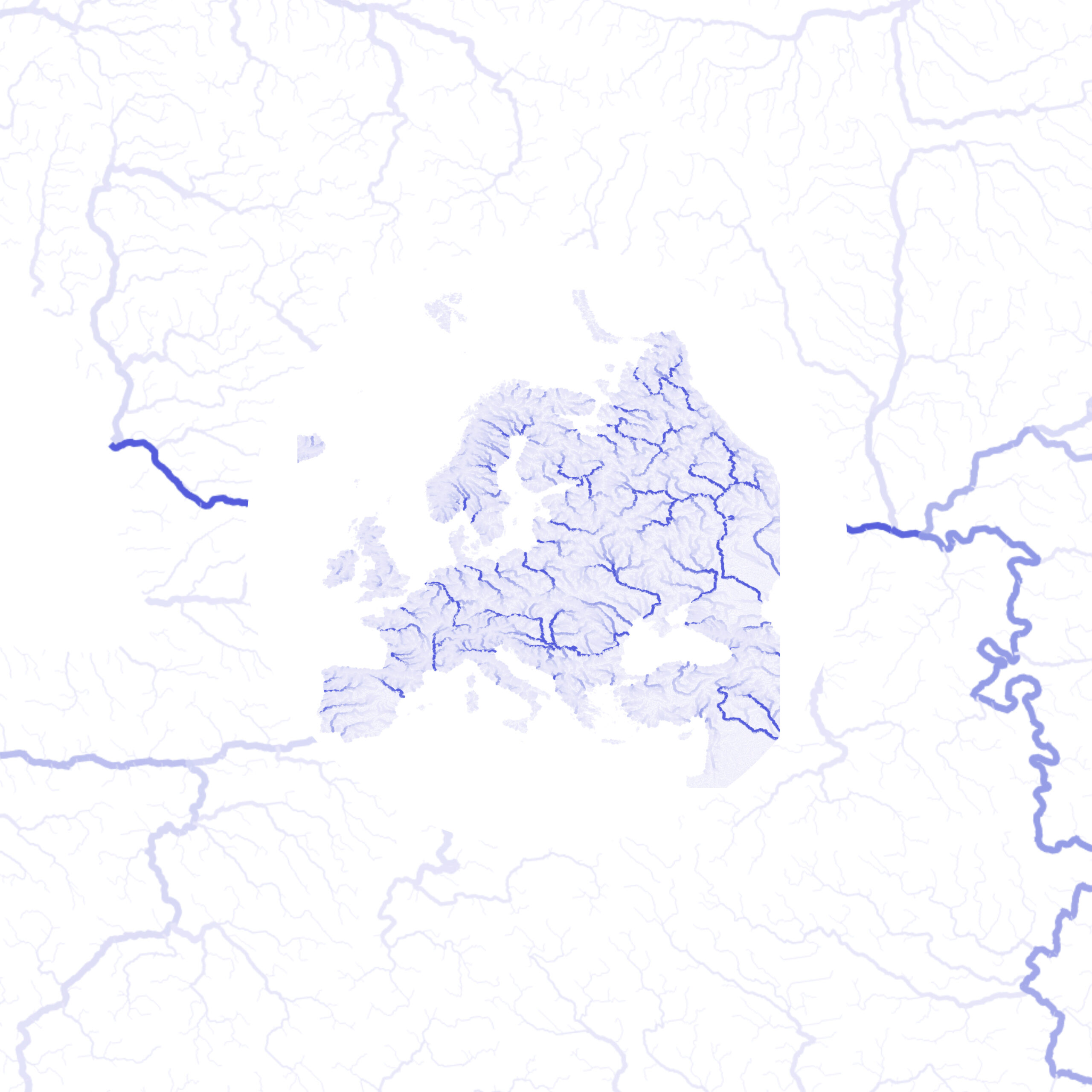

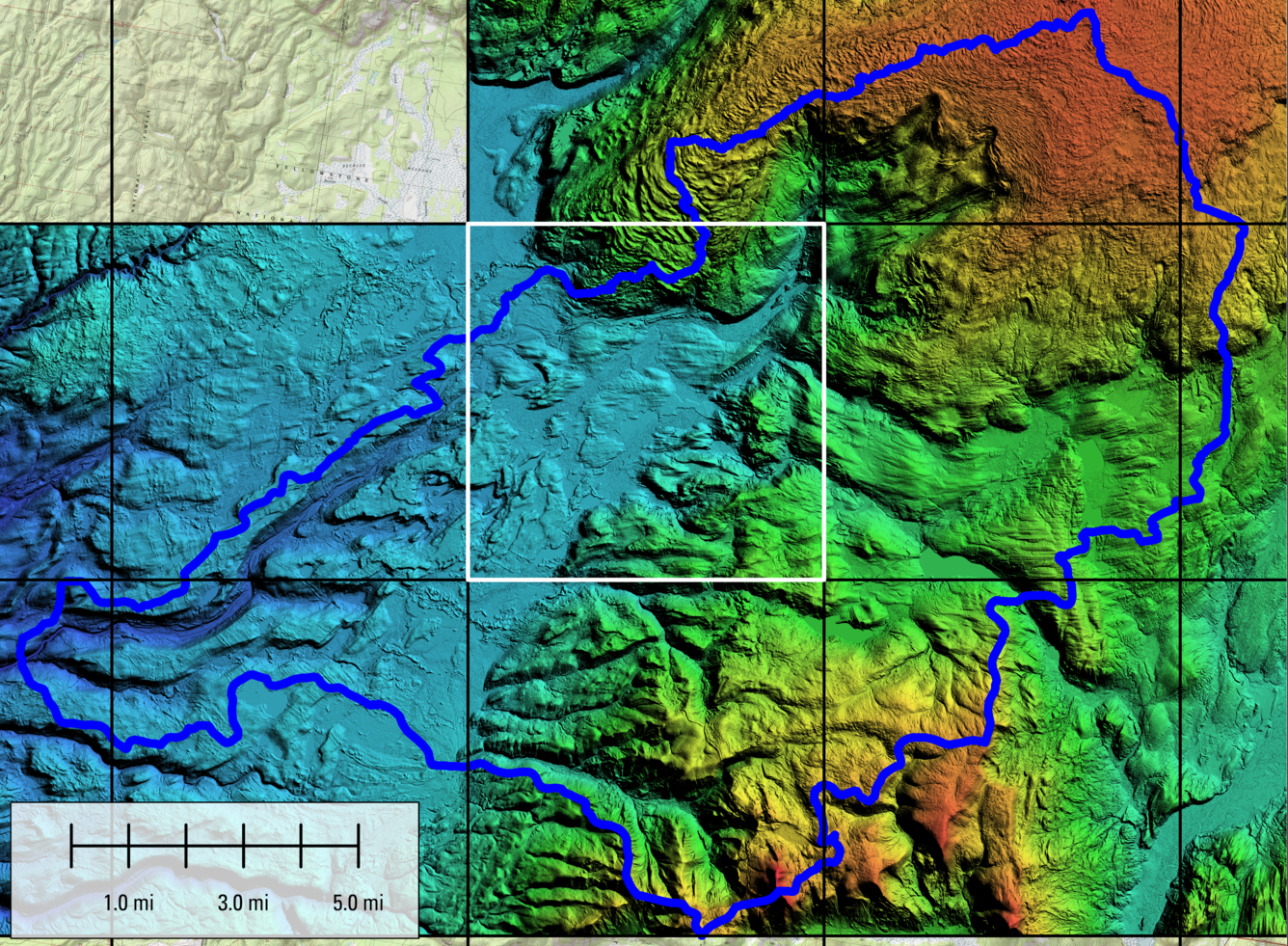

Parallel to these 3D advancements, the USGS has introduced the Seamless 1 Meter Digital Elevation Model (S1M), a nationwide dataset that merges trillions of lidar points to eliminate gaps and artifacts across project boundaries. Beyond technical precision, the “Equal Earth” movement, supported by the African Union, is gaining ground to replace the 16th-century Mercator projection with the Equal Earth projection, correcting historical distortions that shrink the true size of Africa. As explored in William Rankin’s new book, Radical Cartography, modern mapmaking is increasingly focusing on values like uncertainty and multiplicity to tell more robust stories of human experience.

Seamless 1 Meter Digital Elevation Model (S1M)

The AI and Geospatial Revolution

Artificial intelligence has emerged as the “super trend” of 2026, integrating with satellite data to move from simple computer vision to true “machine understanding”.

- Health: GeoAI is now used to detect “green pools” for mosquito breeding and forecast emergency department surges.

- Agriculture: Tools like WorldCereal and Sen4Stat are leveraging Copernicus data to create customized crop-type maps and improve national agricultural statistics.

- National Security: Experts are proposing a National Geospatial-Intelligence Embedding Model (NGEM) that would unify radar, thermal, and text reports into a single searchable “latent space” for automated change detection.

Climate Monitoring: Records and Extremes

Environmental data from late 2025 confirms a warming planet. The Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) reports that 2025 is virtually certain to be the joint-second warmest year on record. This warming has been accompanied by extreme events:

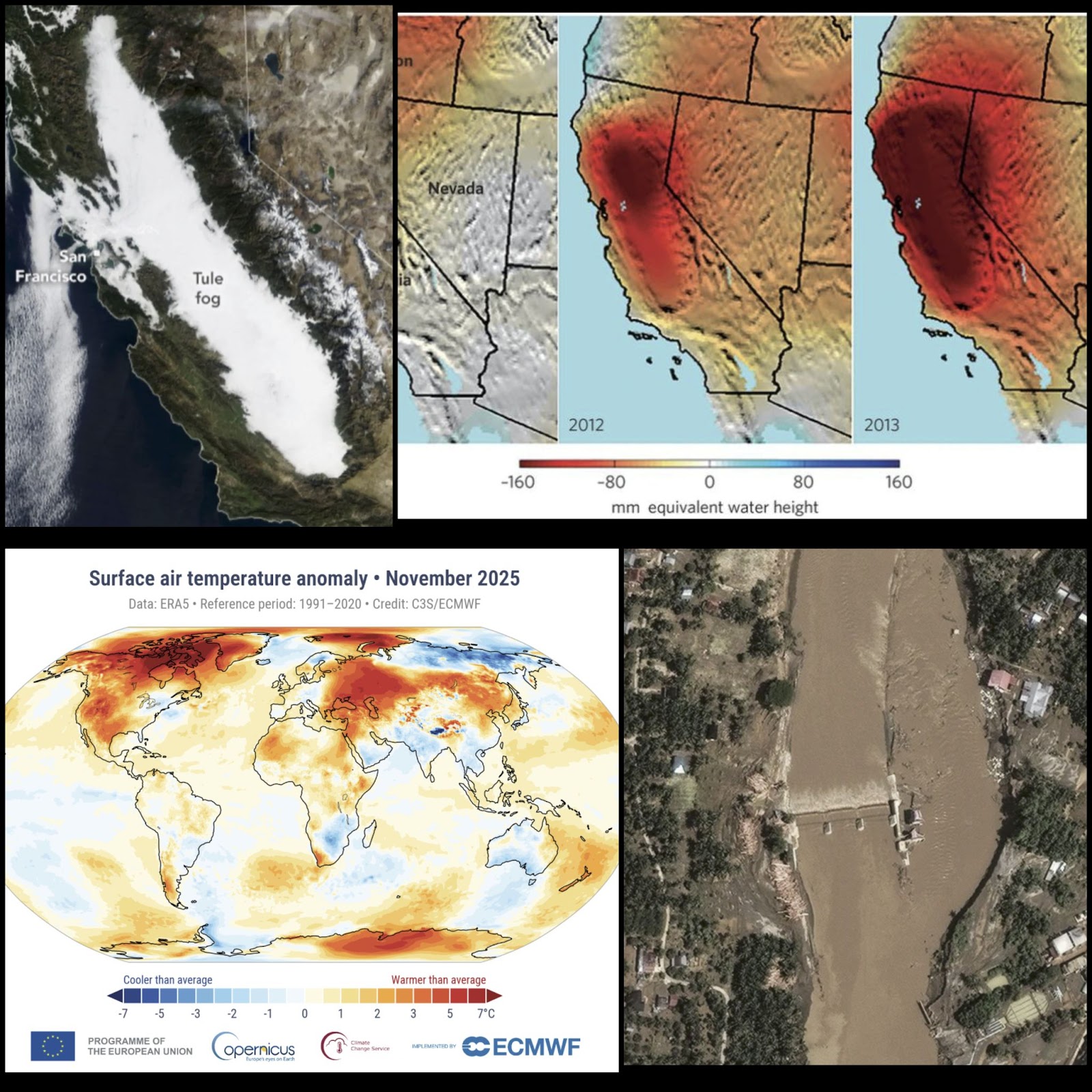

- Persistent Fog: A massive 400-mile-long “tule fog” haunted California’s Central Valley for weeks, trapped by a temperature inversion and moist soil from heavy autumn rains.

- Devastating Floods: Cyclone Ditwah and Cyclone Senyar battered Southeast Asia, causing landslides and flooding that killed over 1,200 people across Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and Thailand.

- Groundwater Tracking: Missions like GRACE-FO continue to monitor the alarming depletion of major aquifers, such as the Central Valley aquifer, which has lost significant water volume over the past decade.

Climate Monitoring: Records and Extremes

Practical Applications: Property and Conservation

These high-tech tools are providing real-world solutions across various sectors:

- Infrastructure: Renewable Water Resources (ReWa) used a GIS data warehouse to manage 177 properties totaling 1,883 acres, facilitating property inspections and riparian restoration.

- Marine Protection: Scientists used ArcGIS Pro to map 52 critical species in the Mediterranean, supporting the creation of new marine protected areas in Greece.

- Field Operations: The latest ArcGIS Field Maps (version 25.3) introduced tasks and improved data capture, with AI-assisted data capture and Geospatial PDF support planned for 2026.

Conclusion: A Connected, Data-Driven Future

The innovations of 2025 and early 2026 demonstrate that we are moving toward a state of “sovereign space” and integrated intelligence. By combining satellite precision with AI-driven machine understanding, humanity is gaining the “decision advantage” necessary to manage resource depletion and climate volatility. As these technologies mature, they will continue to reshape how our societies communicate, move, and synchronize with the planet.

How do you like this article? Read more and subscribe to our monthly newsletter!